Born in 1989 Ukraine with extensive physical challenges, missing bones and parts of limbs, muscle and organ tissue due to in-utero radiation poisoning from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, Oksana Masters was left to fend for herself in an orphanage. The world was stacked against her, and the conditions in the three orphanages she endured were, as she described, truly brutal. But, she refused to give up.

Born in 1989 Ukraine with extensive physical challenges, missing bones and parts of limbs, muscle and organ tissue due to in-utero radiation poisoning from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, Oksana Masters was left to fend for herself in an orphanage. The world was stacked against her, and the conditions in the three orphanages she endured were, as she described, truly brutal. But, she refused to give up.

Then, at age 7, she’d find herself adopted by a single, American mom, whose own years-long journey to bring Oksana home is its own astonishing story. The simple fact that she survived is remarkable. But, she didn’t just survive, once in her home, enduring multiple additional surgeries and amputations, her indomitable spirit refused to let anyone tell her what she could or could not do.

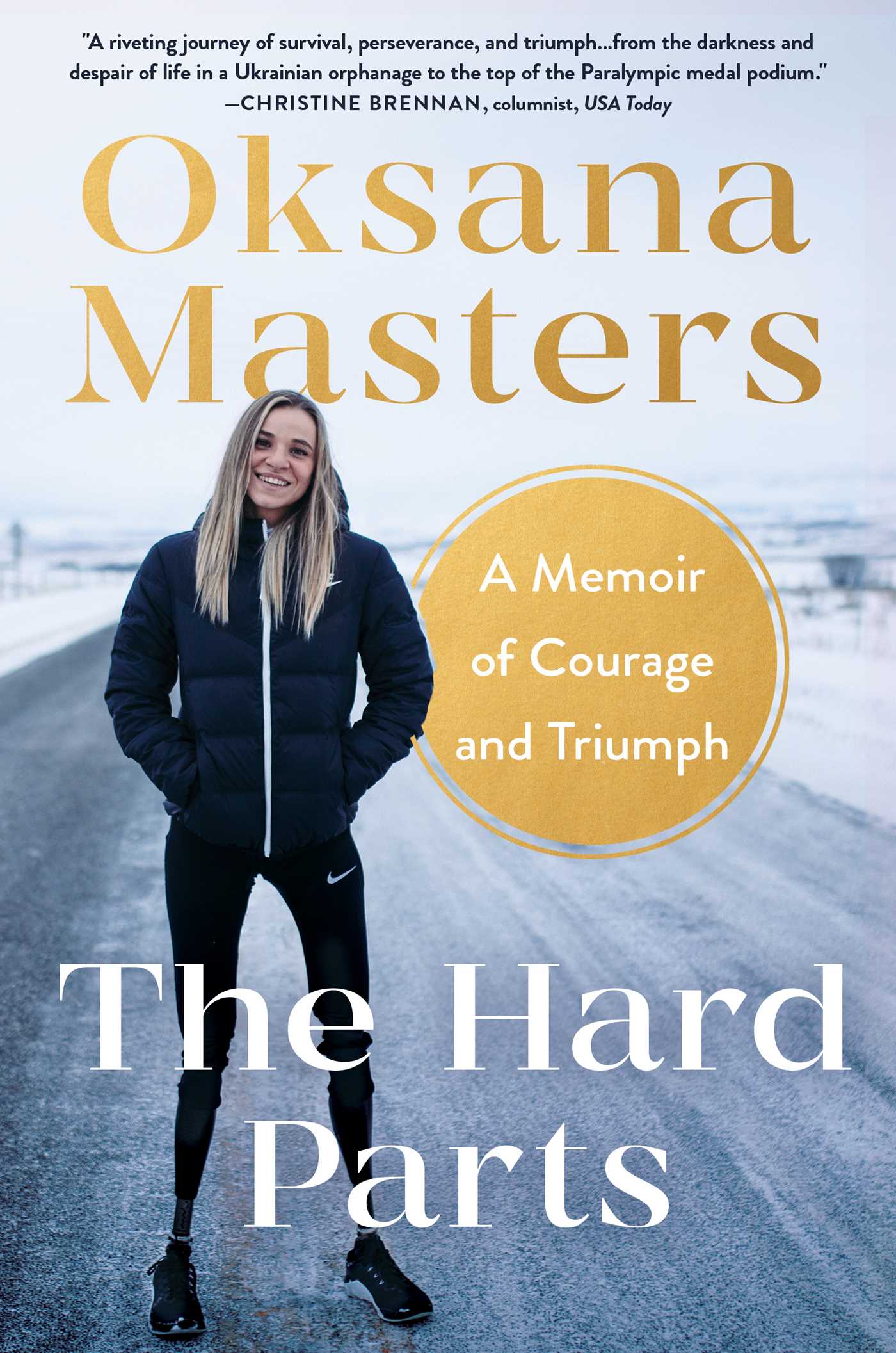

And, nearly a decade later, she’d end up stunning not just her mom, and the local community, but the entire world, becoming the United States’ most decorated winter Paralympic or Olympic athlete, taking home seventeen medals in four different sports. She has since been featured everywhere from Sports Illustrated to The New York Times and has written a powerful memoir, The Hard Parts: A Memoir of Courage and Triumph, that recounts her astonishing journey from the shadow of Chernobyl to the world’s biggest stages.

In today’s deeply moving and inspiring conversation, you’ll discover:

- How an unwavering spirit can conquer the most daunting physical challenges.

- The power of love, support, and perseverance in overcoming trauma and adversity.

- The importance of embracing your unique differences and using them to your advantage.

- What it takes to excel in not just one, but four different sports on the world stage.

- The life-changing impact of a single decision to never give up.

- And so much more.

Join us as we explore the extraordinary life of Oksana Masters, and learn how she turned her greatest challenges into her most exceptional victories. How she became unstoppable, and showed the world what was possible.

You can find Oksana at: Website | Instagram

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Kyle Bryant about how to transform challenges into action.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- My New Book Sparked

- My New Podcast SPARKED. To submit your “moment & question” for consideration to be on the show go to sparketype.com/submit.

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

Transcripts: Transcripts of our episodes are made available as soon as possible. They are not fully edited for grammar or spelling.

Oksana Masters: In 2008, I wanted to make the Beijing games and I didn’t. And that loss was what made me realize how much I wanted to do this. And that’s where I think I learned what I wanted. I learned my identity, I learned my passion, my purpose, and I am so happy to have not made the games my first time around because it lit a fire that just.

I can’t imagine my life without that just burning and fueling me for everything that I do now.

Jonathan Fields: So born in 1989 Ukraine in the shadow of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. My guest today Khana masters, was really left to fend for herself in an orphanage. And that wasn’t all. She also was left struggling with pretty extensive physical challenges from missing bones and parts of limbs to muscle and organ tissue due to in-utero radiation poisoning from that very disaster.

And the world was really stacked [00:01:00] against her. And the conditions in the three orphanages that she would endure, as she described, were truly brutal. But she refused to give up at every step along the way. Until at age seven, she would find herself adopted by a single American mom whose own years long journey, by the way, to bring Sana home is its own astonishing story.

The simple fact that she survived is remarkable, but she didn’t just survive once in her new home and during multiple additional surgeries and amputations over the years. Her indomitable spirit, it just, it refused to let. Anyone tell her what she could or could not do? She was unstoppable and she would not let anyone say anything else.

And nearly a decade later, Sana would end up stunning. Not just her mom in the local community, but the entire world becoming the United States most. Decorated Winter Paralympic, or even Olympic athlete, taking home 17 medals [00:02:00] in four different sports. She has since been featured everywhere from Sports Illustrated to the New York Times, has written a powerful memoir, the Hard Parts, a memoir of Courage and Triumph that recounts her incredible journey from the shadow of Cho Noble to the world’s biggest stages.

And in today’s conversation, you’ll discover how really this unwavering spirit can conquer the most daunting physical challenges. You’ll learn about how the power of love and support and perseverance can help overcome trauma and adversity, or the importance of embracing your unique differences and using them to your advantage, what it takes to excel in not just one, but four different sports on an elite.

World stage level, and we really dive into the life changing impact of a single decision to never give up. That led to a series of decisions for the world to show up for her, to keep showing up for her mom and the community to keep showing up so that she could accomplish [00:03:00] incredible things. And while this story is about her, everything that we explore is about the human condition.

It’s about how we show up every day, how we meet adversity, how we meet, struggle and challenge, and how we ourselves can say yes to doing more and being more and becoming more. Not because we’re living up to someone else’s standard, but because we want to be alive in this time that we have on the planet.

So excited to share this conversation with you. I’m Jonathan Fields and this. It’s good life project.

As we have this conversation, you have spent a lot of years in the world of elite level athletics and won astonishingly a large amount of competitions in different sports representing the United States. But let’s take a step back in time because the journey that got you to this place is really powerful and [00:04:00] unique in a lot of different ways.

You’re born in 89 in the shadow of Cho Nobo. In, uh, Ukraine and you know, I’m thinking this is actually, you know, this is a long time ago now, and there will probably be some folks who are listening to this conversation who don’t even really have an understanding of what happened. So share a little bit about sort of like the circumstances around what actually happened just a couple years before you were born.

Oksana Masters: Yes. I actually didn’t really, because it happened a couple years before I was born, like I think it was like three years. We weren’t educated in the orphanage of what happened and what it was or why we were born the way we were. But in Ensure it was a huge nuclear power plant that is now in like an area in Ukraine, that’s culture Noble where it was, and it leaked and there was a massive malfunction and they, a massive explosion happened and.

An immense amount of radiation just went into the air. What people don’t realize, radiation [00:05:00] levels, it’s been rising and it’s continuing to rise, and the radiation levels that are in the ground, there’s like a large amount of the, like the soil and the crops in everyone’s homes. It’s kind of like a dead area because there’s nothing that can survive there.

People are getting sick if you do go there. And that’s exactly what happened is when my birth mom was traveling, the radiation levels kept rising and rising and rising. They contained it to as much as they could. She ate something that was affected or when she was traveling, it was in the area close enough that it had that much of effect on my developing process when I was in her stomach.

And I think that’s something people are like, oh, but how is that possible when. That happened three years after you were born, and I think that’s the, yeah, staggering, scary side of radiation and what can happen and still happens to kids being born.

Jonathan Fields: So you are born [00:06:00] with certain birth defects. You’re different than a lot of other kids.

And at that point, you, you described her as your birth mom. You end up it sounds like, pretty immediately in an orphanage. Mm-hmm. And this is not an orphanage, this is not what we think about in terms of the foster system or even places in the United States. This is a profoundly different time. It’s a profoundly different experience in Ukraine.

So the early years for you, I would imagine no matter what kid ends up there are rudely hard and challenging for you in particular because you’re also dealing with physical challenges. It turns into just an experience that sounds like it’s filled with fear. It’s filled with struggles, filled with challenge, the literally every day of your very young life.

Yeah. And

Oksana Masters: what the scary side of that is. That became my normal and my outlook in life too, and I didn’t know anything different besides when you see the kids get that, get to go home and see the, the [00:07:00] spark of life in their eyes of like, oh my gosh, I get a family and, and a home to go to and no foster care or orphanage.

Nothing is good to grow up there at all. But extremely more so in Eastern European places as someone that needed so many different medical care that wasn’t provided in that area where I was in Ukraine, where it just, it was pretty staggering the amount of surgeries I was gonna need. And the difference with my orphanage too.

So there’s iNOS and there’s like, Orphanages are baby homes and the interns are owned or government ran. Kind of like how we think of what, um, the foster care is kind of through that system, but not in a very different way. And then the ones that are orphanages are more run and organized by the local communities there.

The most [00:08:00] corruption, the most just dark experiences happen in the government orphanages because it also was just a lot of corruption in that area as well.

Jonathan Fields: So you described needing a lot of medical care and a lot of surgeries. Tell me, uh, what was actually going on with you physically? The, the manifestation of the radiation showed up physically in your body.

Oksana Masters: So a lot of times when people were born with. A disability or a birth defect, it oftentimes will stay local to that area, whether it’s like just the legs or maybe you’ll be in the AM born without an arm and her leg, but the type of the impairment is exactly the same, related to just a standard. I don’t know, like just malformation or something in, in the stomach.

But for me, I had both of my legs, but I was missing the weightbearing bones and then the non-weightbearing bone, I did not pay attention enough in school, so I totally get confused if it’s like it’s anatomy. [00:09:00] Is it like the tibia or the fibia? I think it’s like I didn’t have. The main weightbearing bones were like the tibius.

I

Jonathan Fields: think that’s right. Yeah. I didn’t pay enough attention either apparently in high school bio. Well, I didn’t

Oksana Masters: Also, I’m like, I don’t have legs. Why do I need to know about the anatomy of a leg too? But little did I know it probably would’ve been helpful. The tibia looked like the bone of it on both sides, that someone took a salt shaker and just spread it around.

It wasn’t a fully formed bone. And, um, the knees and there was discrepancy in the leg length. My hands, my toes were webbed. I had six toes. My hands were webbed. I do not have. Like a normal hand it, it’s my little claw, my little t-rex claw. When I came to America, they did a whole lot of reconstruction surgeries, but in addition to just the physical of my hands and my legs, I’m missing part of my stomach and my kidney and don’t have any enamel in my teeth.

And radiation’s the one thing that can strip [00:10:00] it in neutral and. Uh, family or in your mom’s stomach. And, and then I also miss things on muscles too in my arm. So my right side will never look jacked because I don’t have the full bicep, but that’s okay. Mobile compensate with my triceps and making sure that, um, it’s a amount of the things that my body has a lot of deformities on.

It’s just all result of radiation exposure. And also where I grew up in the orphanage in, um, around ky, there’s nu there’s still nuclear power plants that are active to this day there. Hmm. And I remember like, there would be a cop that would go around and say like, we ha we were having a leak just to don’t come out outside at all, let the air die down and let the levels of the radiation go down and then you go out.

So I think it didn’t help the fact that I was. Had massive exposure when I was. Neutral. And then also there was still constant exposures after being born.

Jonathan Fields: When [00:11:00] you are in that state and then you’re in an orphanage, which alone is, is as you described, it’s a, it’s a whole different universe and not a good one.

Um, with a lot of corruption and you have a lot of needs. Everybody around you is said, it sounds like every other kid. No matter where they came from, no matter what, what the level of physical ability or challenge was in a really profoundly difficult place and state, if you remember back to then, did you differentiate sort of like your level of challenge or struggle from theirs?

Or were you kind of like all in it together?

Oksana Masters: No, this is the wild thing. I didn’t know I was different or my, or the, the seven other orphans. I, well, I guess in some ways we knew we were different but didn’t knew that the different was were disabled and how bad it was. And the negative side of it, because it was a government ran institution, part of it was like a boarding school, but not the boarding school that you think of where you get this amazing education and all this stuff.

It. [00:12:00] Was where families didn’t have the resources or the money to actually raise their kids at home. So they would pay X amount very little to the government, and then they would stay there and get their education, have room and board and food there, and then on holidays or whenever they wanted, they could leave and come back.

So there were like at a time around 300 kits. There were seven of us that were, and they were all healthy able-bodied, no disability that. I knew of, I didn’t even know what disability was then. I knew that from that, I guess, like they got around different, I didn’t think I was disabled or we were disabled.

The seven of us that were there, I. Until I came to America and people started pointing out, oh, I walk weird. Oh, my hands are weird. Oh, like, why do you, you look so weird. What’s wrong with you? And it’s kind of interesting as a kid, like all your, your mind and everything’s being formed already and how like you view the world and how you view yourself and stuff.

And, and I [00:13:00] was always that very physical, active kid. I never thought anything different of like, I get around differently. I’m just thinking like, okay, well I wanna go up the stairs. I wanna run down the hallway as best as I can too, and. I guess the only way, like not only, but we really bonded close to some of the darker times in the orphanage, like and then especially when we’re all really, really hungry.

We all knew what that feeling was and so we would try and save food and try and help each other in that and bond over that, not necessarily the our bodies. We’re different and bond over that, if that makes sense.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. It’s really difficult to fathom the fact that the first time that you actually sort of like realize you’re different in a way where maybe other people are judging you is when you actually come to America.

Mm-hmm. And which you would figure would be the place where you start to actually really, like, there’s all these benefits, there’s medical care, there’s family, there’s community, and yet this is the place where a certain label starts to get placed on you that you never placed on yourself or felt in those early

Oksana Masters: [00:14:00] days.

And the weird thing about that was too, the time that label was being placed on me was the exact same time I was, so I didn’t speak English when I came here, so I was learning a whole nother language, and so I was learning a whole new home, a whole new language, and then learning that I was different. And so I think why?

I grew up with such a hard chi, like such a hard time accepting my body is because my first words about my body were what I heard from other kids and didn’t know how to understand that, and that is a whole different thing to try and process. When those are the first words you’re learning about yourself, and then to re relearn and, and retrain society, but also retrain your mind and how you view yourself also.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. It, it’s like those are the first, I mean, you’re literally having to learn an entire new way to communicate a new language. And the first words that you’re hearing are the ones that describe you as being other. Mm-hmm. Um, yeah. Which has gotta be, I mean, brutal experience no matter what age you are, but especially at that age, really young and formative.[00:15:00]

Talk to me more about, um, the experience of. Leaving the orphanage because you end up adopted by a mom who’s in Buffalo, New York. But apparently this was not like a couple of weeks and this whole thing happened. This was a multi-year process with a huge amount of challenge. Um, so walk me through this a little bit and, and, and what was actually happening with the woman who had become your mom.

Oksana Masters: Yeah, and so I actually talk a lot more about my mom’s side of this journey that I actually had no idea more about in my book, but it was just bad timing for my mom’s. She was also adopting me as a single parent, and it’s extra challenging. The adoption agencies for international, and both in Ukraine and in the US had to.

She had to take so many extra like psychiatric tests and find out, well why? What’s wrong with you? Why aren’t you married? And just always hounded her on that because at that time it still is, but not nearly what it was in 97 when my 95, when she tried to, in 97 when she got me to try and [00:16:00] adopt and she, there was some like political things and what ultimately happened.

So she found out about when I was five and then the, there’s a moratorium that was put on all foreign adoptions, like a ban in Ukraine and then also on the US side. There was one that was put on afterwards and they told her, we don’t know when these adoptions will be. Like, the ban will be lifted at all.

You can go and adopt a baby from Russia, you can get that baby within a few weeks. And at that time she already like submitted the paperwork and was, I don’t know what she saw in that picture, that black and white, creepy picture of me that I think is creepy, not good, having a good hair day. Thank God for her heart because she bonded with that and something in it.

And that and with me. And she was telling everyone, this is my daughter. I’m gonna wait for her as long as it takes. What she didn’t know during that process, and she thought I didn’t know anything about her. The orphanage directors did not [00:17:00] tell me about my mom, but they did. Because I was asking to look at her picture every single day, and I would just try and, and it was a little small passport picture that she had to submit with the adoption process.

And that’s the picture the director of the orphanage would let me look at. And I just memorized it. And it was hard because like, I didn’t know. Why it was taking so long to get her before them telling me like, Oksana, we have, we’re gonna be, have a new mom. She’s in America. She’s gonna come here to get you.

I had two other specific family members I remember so vividly that told me I was going to be part of their family. They were gonna be my new mom and dad, but then they never come back for you. So you kind, I got used to that. Used to have like up being forgotten because that was just the normal. So I didn’t wanna get my hopes up, but with her looking in that picture and her eyes, I kind of felt like it was different.

And then ultimately what ended up happening [00:18:00] in that process was the director of the orphan. I was a very mischievous and just troubled make her child. I did not, I was not that good girl that would just like, like, don’t touch that button. I’d be like this one. And it would push it entirely. They started saying that, well, it’s because you’re a bad girl.

This is why your mom doesn’t wanna come. She knows it. She sees what you’re doing. And when it’s a year and a half later and she’s still not there, you’re like, oh my gosh. Like she does see, I’m a, I’m a bad kid and she doesn’t want me because of this. And when the band lifted, she ultimately went to Ukraine and got me.

And they, even when she got to Ukraine, there was a whole lot of trouble. It was her. And then my, um, aunt Sherry went with her. My Aunt Sherry’s the courageous, adventurous one. My mom is the very cautious one that’s like, oh my gosh. And that’s this kind of history. She saved my life in that because it was so easy for her in that moment, be during that hard time.

She’s like, I don’t think I can do this. [00:19:00] While still giving, having people show her other pictures of other kids. The wild thing about this, Jonathan, is that she wanted a baby. She didn’t want a seven year old opinionated girl either, which I was very opinionated and thought I had the world figured out at that point.

All in Ukrainian.

Jonathan Fields: So do you remember the moment that, that you first saw her there for you after like almost two years at that point and, and maybe hanging onto the belief that maybe this would still work, but like with every passing day, like probably being less Sure.

Oksana Masters: Yeah, I was less sure, but. I’ll never forget the day when I met her because that it was ended up being at night.

She was supposed to come during the day, but because of flight delays and all that stuff that life happens, um, she ended up getting in late at night and I threw the biggest hissy fit because I. She was, I, they told me she was coming that afternoon and I thought, if I go to bed, she’s not gonna come. Like, it will, it’s gonna all go away if I close my eyes.[00:20:00]

And I didn’t want to. So I was just like, no, no. And I was just that brat, like I was talking about my life and their heart life extra hard. And ultimately I went to bed and, um, my mom, my Aunt Sherry were on the Man I’m direction. I’m like so directionally challenged. I used to remember my left and rights because my.

Left leg was amputated. So I’m like, okay, left. I’m missing the leg. Right? I’m not missing a leg. But now they’re both gone. So I’m like, oh my gosh, which is my left and right. She kneels down with a translator and the director of the orphanage and they wake me up and they say, Oksana, do you know who this is in Ukrainian?

And my mom is wearing this dark black long coat with this fur around it cuz it’s in winter in Ukraine. And, and I look at her. And I’m like, the first thing I said in Ukrainian tour was, I know you, you’re my mom. I have your picture. And I got out that picture that they let me go to bed with that night next to my bedstand.

So I would stop throwing that hissy fit. And my mom said, well, I know you, you’re my daughter. And then she gave me this [00:21:00] stuffed animal that her mom that passed away had made for all of her kids. And it looks like an elephant, like a Dumbo. And that was, The first toy I’ve ever received and never had and never saw, and never felt.

So it was the first time I. I went to bed with a smile on my face and felt so content to be in that place where it was for the longest time, the scariest place to be.

Jonathan Fields: When you end up going back with her, as you described, at that point, you’re not speaking English. Mm-hmm. So I imagine. The next couple of years for you and her, as she’s learning how to relate to you, you’re learning how to relate to her.

You’re learning an entirely new language and way of being, and also as you described some of the words, the first words that you’re hearing are starting to really describe you as like how you’re different than everybody else, beyond the fact that you’ve actually just lived in an orphanage and you come from a different country in those earlier days.

If you can think back to it, I’m, I’m curious what it [00:22:00] was like for you. To start to find new ground, an entirely new place. On the one hand, you’ve got a mom, you’ve got a family, you’ve got safety for the first time in your life, but there’s just a profound level of adapting and change that you’re dealing with at the same time.

Oksana Masters: I think that’s the beauty of also, like kids are so resilient and so adaptable on the fly. They don’t think about it. They just do it, and I think that. Part of being so, um, physical and hands on and just always active, mixing, being with a kid and just trying to, I never, I grew up that like trying, I always trying to keep up and I had to keep up, otherwise I wouldn’t survive in the orphanage.

So it was just like a part of. My D n A already, but my mom also, she knew when I would come to America I would need to have multiple surgeries. The first one being amputating, my first leg. But because that first year she wanted to wait when we got to America to [00:23:00] bond to her. So like we were saying, like adapting to the new surroundings of the new language and to what a mom is and what a home is, and what a family is and trust and.

I grew so much within the first few months and my mom said it was food, but a lot of it was just the human touch and affection that stimulates the growth hormones to also do that. And I was very active and just loved to always feel like adapting was so natural for me because of the environment that I came from.

And it was becoming really hard. I got my first like amputated and that was pretty easy to be honest, because it was planned. The doctors knew what they were gonna have to do, and a year later, after. I’ve already bonded with my mom. I had the left leg amputated be, um, because like my knee, that my whole leg was just so much shorter than my right leg and the knee was growing off to the side in like a c shape and [00:24:00] that was my little leg.

I went to bed with it every night holding onto it. And my mom and I, we had like a little goodbye ceremony for it the night before and she made me, before all my surgeries, made me a Ukrainian meal, which is really interesting cause I never had food in Ukraine. So, but I, like, I’ve smelt it from the other kids having it.

I just never got it. She always tied in where I came from to like new, big experiences in America now, and I think that helped the whole adapting smoother. It became a lot harder. When I got older and more aware of things, like I actually understood what the words meant that I was saying, and I understood how to process it and form my own thoughts, and that’s when that became challenging.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. I mean also at a, at a certain point you have to just as a human being, grapple with the fact that there’s a huge amount of trauma in your early life. Mm-hmm. Well, I didn’t

Oksana Masters: even know it was trauma. Yeah. Like when, I guess like, To piggyback a little bit more like on adapting the hardest [00:25:00] thing that was to adapt to that you think would be the easiest thing was having a warm, safe bed, having your own room, having toys, having love.

Yeah. I was so uncomfortable by it. I was, my body only knew. How to live in fear. And so it became my normal, kind of like what I said earlier at the beginning of this conversation is that was the one of the hardest transitions physically, like I can figure it out, but that emotional thought thing of like, oh my gosh, this is too badly, this is too comfortable.

I, I slept on the floor because it was more comfortable, it was more familiar from my body and trying to rewire the way you think of. What a home is and what, and that’s when I started realizing what I went through was the trauma and the experiences and abuses was not normal. That was never Okay. Um, but yeah.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. It sounds like along the way also your mom picked up on your physicality. I. And just would literally try and like support you in pursuing anything [00:26:00] movement oriented, anything athletic oriented. And you were out there saying, no, I wanna do this, I wanna try this and I wanna try this. And it sounds like on the one hand your mom is supporting this, but then in other ways, other adults weren’t.

Like you wanna try out for something and all of a sudden the like the quote, responsible adult is like, no, you can’t do it. You know, you have a prosthetic and quote, risk to other kids,

Oksana Masters: liability for them, but what about me?

Jonathan Fields: So it’s like you’re getting shut down at every turn, but physicality, it seems like was always something.

That for some reason you are drawn to and that starts to show up in you participating in sports and, and it sounds like your mom really picked up on that and said like, how do I support this in every way that I can? My mom’s

Oksana Masters: incredible. She definitely, um, she saved, I say that she saved my life so many different ways.

Two specific ones was obviously adopted me from the orphanage because when I came to America, they said if I was living up to 10, I would not have made it. Past that age, just because [00:27:00] I was considered failure to thrive. I was the size of a three-year-old, not almost an eight-year-old when I came here. So she saved my life from that.

And then she saved my life by opening the world of sports. And instead of, I don’t know, like she definitely did not get me into sports to think, oh, she’s gonna be an athlete. She wanted me. In Buffalo, New York, there was an adaptive ice skating program, and I think she saw how active I was and how determined I was by one experience when I was trying to climb the monkey bar or the on the swing set.

They have like this, um, thing, you know how kids like, I don’t know if kids do that anymore. You just like go on your hands across like the swing set. I watched my friends do it and I couldn’t figure it out because they were doing it with their thumbs and I don’t have it, and my hands were also, I haven’t had the surgeries for them yet.

My mom told me, well, I think this might be one of those things that you won’t be able to do. She went to work the next day and they were a [00:28:00] babysitter. All I did was just made her watch me. And be outside and try to get to the monk through across the swing set. And then when my mom got home, I was like, mom, look, look what I can do.

And then I finally went across without falling and she, that’s when she realized like, okay, I am will never say you can’t do something anymore. And I think when she saw that determination, along with just always wanting to be active, that’s where she introduced me to ice skating. And it was only to.

Really make friends and like learn the language and make bonds in the community and see people that were like me also with maybe physical differences and just she thought that’d be the best way to do that. And I fell in love with it cuz I saw other kids that look different. I’m like, oh my gosh, is this what I look like?

But I never really thought of myself at that time yet at all. And because all I was feeling was being free on the [00:29:00] ice and feeling that cold air and just that movement that my body has in a different way of never experienced and. That transformed when we moved to Louisville, Kentucky to doing horseback riding, which I was like, oh my gosh, this is the end of my life.

We’re moving to Kentucky. What do people do there? I don’t even like country music. I mean, now I do, but back then when I was 13, I definitely did not. And she’s like, well, you know, everyone that’s in Kentucky has to learn how to ride a horse. And so you’re gonna have to learn that. And I think she saw how and knew how healing and therapeutic.

Movement of body is, and sports and the power that had, it wasn’t until way later that it became competitive and that we realized that like, oh wait, you can actually race.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. I mean, it sounds like, I guess your early teens around 13 or so, when, you know, someone suggests, well, there’s this thing called adaptive rowing, but it also sounds like you had a resistance because mm-hmm.

Because of the word adaptive, and you’re [00:30:00] like, no, no, no, no, no. That’s not for me. Like I want, I want the quote real thing, or like the thing without that word in front of it.

Oksana Masters: Yeah, well, it’s like another label that was being put on, like hate being labeled as an orphan because at that time I was an orphan.

My mom, I have a home now, and now I’m like disabled and then now I have to do an adaptive sport because I have disabilities. That’s where me at seven and a half thinking I had the whole world figured out. 13, it just got worse. I thought I for sure had it all figured out. Then two of my opinion got even bigger and, but because I wanted to be part of what my friends in middle school were doing, I wanted to be in that dance team and instead of beings in the volleyball team, and instead of being supported, I was just, For the standard normal dance team, I was, my prosthetic was a liability for the other girls.

And then Randy Mills, who kind of worked within the school systems, made sure people with kids with. Physical differences were able to get around in their classes, ran the Louisville Adaptive Roaming [00:31:00] Club and said you should try out, and I was so resistant to it because like you said, I didn’t like the way that it was just another label.

Just because I’m missing a leg, that one leg at that time doesn’t mean I need to do an adaptive sport. And. I guess in some ways that was like another way of society telling me of where I’m gonna be, that box of where I’m gonna live and where I belong without even giving me a chance to try and figure that out.

And, but oh my gosh, thank gosh that I did cuz my mom was, my mom’s like that key, like she is just like that like. That constant, like every part of my life, it comes to my mom being the reason of guiding. And, um, because she just said, well, just go out and try it. You could try it once and never do it again.

And that’s why I was like, okay, stop asking me. I’ll go if you, if you stop asking. And oh my gosh, I fell in love with it. And that’s exactly where my life changed. And the world of sports truly opened up in a way that I [00:32:00] never saw

Jonathan Fields: coming. Tell me about that first moment when you’re pushing off from the dock, the first time you were in a boat, and what that feeling was like for you.

Oh

Oksana Masters: my gosh. I was terrified to take my leg off, but I also am biased cause I love rowing. I feel like everyone in this world should try to get in a rowing boat once and you will understand the feeling I’m talking about because water is just so powerful and so therapeutic and just healing and. I’ll never forget where I pushed off the dock, leaving my leg behind and my oars like I could just feel the water and the boat shift under under me, and it’s exactly related to what my hands were doing.

I was controlling it and for the first time after that first stroke, and then like five strokes later, like I just felt like I belonged somewhere for the first time. It was something internally that clicked for me. That I really felt so happy, and I think I was happy to have a mom and happy to have my new home and [00:33:00] everything, but a part of me was a little bit like I was 13 and I was also, at the time that I tried rowing was around the same time that the doctors in Kentucky said, we’re gonna have to amputate your leg.

We can no longer save your second one. In addition to that, a lot of memories that I just suppressed and I told my mom, nothing bad ever happened. Everything was good. We’re coming because there’s only so much you can bottle into a box and tie it up in that bow and pretend it never happens before. It just sits there for such a long time.

That box is gonna get worn down and things are gonna start coming out, and that’s exactly what it did. But I was so lucky that at that time, that home and that lighthouse to always go to was rowing for me. It’s

Jonathan Fields: interesting you used the word control. And it sounds like that was also this moment where so much of your life had been controlled by other people or by circumstances.

And like you push off and you’re in the boat and it’s just, and for the first time it’s like you are [00:34:00] in control. You are powering this thing like fast, slow, sideways, like whatever it is, it’s just you.

Oksana Masters: And that’s something that’s So then specifically it’s the better now because adaptive sports has just grown so much, but back then, I also never, like I fell in love with the release.

When you go to the catch, which is the first part where you, the oars drop into the water and you pull on the oars and you just feel this tug. And then there’s a part that’s called the finish of the stroke and you release and every, the oars and everything just come light. You feel this just popping up outta water.

And so it became a way for me to just like, just let everything out. Like scream, but scream silently. Not having to actually like everything out and process my thoughts, process of how, how I move my body. And then that control helped me see what I did have and what I was capable of doing, what I was capable of controlling.

And it [00:35:00] was the only place. That I had control of me because when I came here, I had a lot of psychiatrists and doctors saying, oh, she’s gonna need medicine for the rest of her life. She’s gonna need therapy for the rest of her life. She’s never gonna be able to have a healthy, stable relationship from things that they were diagnosing me with.

So I had people telling me things about my physical appearance, about my mind, because based on my experiences and then in society, just being someone that. Society’s limited views of people like me and what I can achieve. And so it was just that escape where it was just me and I needed that without talking and that just that dialogue with me, my heart, my body, and my mind to just truly learn how to love myself and appreciate what I can do, and not focus on the outside noises and making that voice being the louder voice to hear versus.

I am strong and I can do this without legs. I don’t need this. And there’s so many different ways [00:36:00] to, to just live life.

Jonathan Fields: It sounds like also it’s the physicality and rowing for anyone who’s ever tried it. You know, it can be intensely, intensely physical. Oh yeah. That, that physicality was also. It was this outlet, like a really powerful outlet as memories are coming back mm-hmm.

Um, that you had had repressed as those start to flood back as a teenager, you’re trying to figure out how do I process this? Sounds like the physicality was a huge outlet to channel that into something rather than dysfunctional. And destructive. Something that was empowering and I’ve heard you describe, I can’t remember where I heard or read this.

Describe it almost like, like your ability to scream. You know, but it was, you were doing it through physicality and through movement. I

Oksana Masters: think like, cause a lot of people are like, oh, well I’m not athletic. I can’t find my thing, my outlet. But I think for me, I needed that physical release, that physical outlet.

Something where I could feel my body. It’s kind of like you ever just [00:37:00] like wanna go and you just like scream in a pillow and you feel 10 times lighter. Or you just like, I don’t know if you go boxing, you just feel like you’re like, ooh. Or a good run. For some people it’s journaling. Like it can be you just journal or you get lost in that book and you put that book down and you feel ready and energized.

It’s, it’s finding that escape for you and for me it was sports. It was a way for me to, I’ve always been that physical learner and to see it and feel it and do it. I think we all have that cuz it hurts me when people say like, I haven’t found my thing. But I think when you’re open-minded to not being afraid to just let that thing you love.

Like that is your escape. You just don’t know it. Like you just get lost in that thing that you love. And for me, I was not afraid to sometimes every be day. He’s like, I would scream, it felt so good to let all that anger and that figure out that was holding me down and that was really toxic to trying to help me truly love what I see in the mirror.

And [00:38:00] that love my reflection, all of it, not just, not just from the chin up kind of thing, because makeup.

Jonathan Fields: At certain point though, I mean, so this is 13, 14, and as you also described, the doctors were right around then saying, well, yeah, we’re gonna have to amputate the other leg also, which requires you to, to almost kind of relearn how to step back into the boat, how to row, how to stabilize yourself.

It puts you into a whole new thing because without that joint, things are different. Like there’s a, you know, it completely changes the balance of the way that you move. Um, and especially on the water. If anyone’s ever rode or been in a skull, they’re really narrow, long, delicate things. Have you rode? I have, yeah.

Um, and I’ve ended up in the water also as everybody does at some point. But, um, at some point this becomes, I. Something more than a passion, something more than an outlet, something more than a coping mechanism, something more than like this physical expression for you, and it [00:39:00] turns into something that says, this actually I wanna take to a higher level.

It becomes something which almost sounds like it forms around an identity and part of that identity shifts to. Maybe I could actually compete and maybe this could actually be something that becomes almost like a central devotion for me.

Oksana Masters: Absolutely. And honestly, to be honest, I didn’t still see that I could compete.

I did small races here and there and realize, oh man, I’m competitive. I’m really competitive, but. It wasn’t until in just right before 2008, Randy Mills says, oh, you can, you’re young and you’ve got a future in this if you want to go to the Paralympic Games. And I’m like, what the heck is the Paralympic games?

I’ve never heard of it. So I had to Google it and f figure out what it was, and there was much less on Paralympic games then in 2007 than it is now. But I fell in love with the idea of. Representing something so much bigger than yourself, and it became, like you said, [00:40:00] identity and having that identity, it became a way for me to represent where I came from, like for all the little kids who were adopted and coming from international adoption.

And it’s just, I fell in love with it, but I didn’t know I could still be competitive at all or consider myself an athlete. And because I never saw it and you can’t. You know there’s, it’s very common now saying you can’t be something that you never see. Cuz the small races that I was doing up until learning about the Paralympic games, I was doing well and competitive, but I didn’t really see myself as an athlete either doing it.

And then long story short, 2008, I wanted to make the Beijing games and I didn’t. And that loss was what made me realize how much I wanted to do this. And that’s where I think I learned what I wanted. I learned my identity. I learned my passion, my purpose, and I am so [00:41:00] happy to have not made the games my first time around because it lit a fire that just.

I can’t imagine my life without that just burning and fueling me for everything that I do now.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah, I mean, it’s so interesting though because having really tried for it the first time out and then not making it, this is almost like there’s two paths you can go from that point. One is, well, maybe I’m just not cut out for this.

And the other is, you know, like basically, oh hell no. Like, like, okay, so this wasn’t the time, but this is the path and all this is doing is making me want it that much more and work that much harder.

Oksana Masters: Well, especially since after that, um, those trials, I. One of the women who picks the teams and stuff that worked in US Rowings, she was saying that, well, I’m just, it’s unrealistic kind of goal because I’m way too small of a body frame.

I’ll never be an elite athlete. So on top of that, it was one more person in a voice saying what they [00:42:00] thought was better for me instead of like, Seeing potential and just learning, having time to get better at it, and just automatically judging me on my body size. And I am, I’m one of the smaller athletes.

I know that, but that means my tempos. I’ve learned how to compensate for my lack of mass or whatever. That’s why I love to climb. But that really, really fueled me too, is when someone’s like, well, This isn’t your path when, when I knew it was.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. It seems like every time somebody drops into your life and says that to you, you’re, you are, whether you say it out loud or you think it, it’s just like, just watch me.

And that, it seems like that’s almost like that’s been this consistent inner mantra for you. It has going through everything, and there’s like a flame inside of you that just refuses to get extinguished no matter what goes on around you, because you know, as you. Evolve. And so you start training again.

You find a partner, uh, Rob, former Marine and you’re rowing together and eventually [00:43:00] London comes. You do make it to the Olympics and you actually you medal for the first time. What was that moment like for you?

Oksana Masters: Oh my gosh. I was like a kid in a candy store where your mom just says, pick out anything and everything you want.

I was like, yes. And I love this picture cuz I’m just smiling from ear to ear and Rob’s just like standing so stoic and just like, Because he’s like, we could have gotten gold. And that’s what, cuz we got bronze and I was just so happy. We were the most, we rode together for like a little, like little, just under a year really together competitively.

And we were the smallest crew, the least experienced crew. So I’m just like, oh my gosh. Especially from my perspective, going from not making it to, not only making it, but then seeing your flat being raised was just amazing. And. I’ve never like my legs inside my legs on the dock, on the water. That is the most terrifying place to walk if you can feel your legs.

But then it’s even more scary if you can’t feel it where you’re walking. They were [00:44:00] just shaking cuz I was just so happy and I could see my mom and my aunt, my family were there and the American flag and Rob’s parents were there. And it’s one of those things that like, I think I was really lucky that my first, I had two separate mixed feelings and thoughts in that.

Like I was so lucky that. There’s nothing like celebrating with a team with like another partner there. It’s amazing as an individual sport on your own, but I think what made that moment so special is because I put in a hundred thousand percent for Rob and he was doing the exact same thing for me, and it was just to prove everyone wrong.

Together and to bring the home. The first medal in that category for rowing was just incredible and, and then Rob’s face in that picture really just inspired me and fueled me like, okay, if Rob thinks this, then hell yeah, we can get the gold then. But it was an amazing, amazing feeling.

Jonathan Fields: Yeah. That’s amazing.

I’ve known people who’ve, um, I, I have a number of friends, like colleagues that have like participated in different sports and [00:45:00] Olympics and it’s interesting and there’s, apparently there’s this phenomenon for silver medalists where it’s actually psychologically better to have bronze than silver, because very often silver medalists fall into profound depression because they’re like, I was so close, I was one away.

Whereas bronze is kind of like more at peace with the fact, yeah. You’re like, woo made it right. It’s like, okay, so I made the top three, like, I mean, I’m good and there’ll be another, you know, like shot four years from now if I really want. Over a period of years, you also start to expand the sports you’re working on, and for various reasons.

One, shifting interest, shifting body, sometimes injury, meeting the right people. Mm-hmm. Who introduces you to CrossCountry and biathlon, which for those who don’t know, is a blend of, of shooting and Nord CrossCountry, I guess. Mm-hmm. But along the way, as you’re going, you know what I’m getting curious about also is one of the things that you just said is like, once you start to realize you can compete on an elite level, You also had this thing in the U that said, I can represent a certain [00:46:00] ideal for kids who were not necessarily had your exact story, but had all sorts of struggle, or you know, like for whatever reason were told you can’t, it’s not possible.

Mm-hmm. But at the same time, I also know you felt really strongly about this notion of how your story might be perceived. Mm-hmm. And wanting it to land in a very particular way. Yeah,

Oksana Masters: I was so terrified to share my story. Well, first I didn’t see any power in my story. I hated it so much. Adoption story in general is different to, and is unique to each individual that is adopted.

But I compared myself to some of the people that I knew were adopted. I’m like, why? How are you? Can you talk about this so easily when I hate everything about it and then just like still processing to truly accept me in my body, my physical appearance, and see the power and strength in my story. I started sharing it and I kind of had to learn.

I had to like do my own [00:47:00] personal inner growth and truly learn how to love myself before I could see the strength in it. And learn how to use those challenging moments and those harder parts as my secret weapon on that start line to fuel me in a positive way instead of fuel me in a way of, of fear and just never wanting to really live life and everything it has offered.

And I started sharing parts of my story through sports and interviews and was getting a lot of kids and family members that were saying, thank you so much. I ignore exactly. What you went through, cuz I went through this too and I’ve never heard anyone say this. And it helps me knowing you went through this so I can get through this too.

The one that I had no idea was gonna, that hit me a lot was parents who adopted and saying Thank you for sharing your story cuz I understand my child more and will know how to be a better parent. And so there’s the adoption side and then there’s the sharing and showing society of not seeing me just like what I have and what I [00:48:00] can do.

So I was afraid that all those things of being an orphan, being abused, being somebody with a disability, being a female in sports, being like just all these things that I was afraid when someone knew the whole real story of my life, they would feel more pity then would just feel like, oh wow, what I want people to do.

To learn from my story is recognize. We all have hard challenging moments. We all come from setbacks that we have to overcome and, and there’s no such thing as who had it worse, what was a worse experience to live in? Because it’s all unique to our own shoes and what we walk in and what we know. What we can do too is take those hard moments and they can be our fuel.

They don’t just have to be that negative memory that we wanna suppress and get rid of and never forget. It’s part of who made you, you. It is in your D n A. It doesn’t have to define you, but you can use something to fuel you to. [00:49:00] Once you tackle it on work through it, it can be your secret weapon and you can feel 10 feet taller when you look in your life.

And you know, something that I’ve really realized in this process of writing my memoir is my personal journey of where I came from in the orphanage to where I am now as a human. Is parallel to my journey as an athlete too, which was not making the first games. My gold medal was not the first medal that I won.

It was a series of up and down, up and down, good and bad. And it paralleled. And I think that’s what I really realize and what I hope people realize is that each moment creates our character in how we, but it’s only if we choose to see the power in it instead of just the. The bad side of it and the fear of, oh my gosh, if I try to work through this really scary memory moment, like what is it gonna do?

And. [00:50:00]

Jonathan Fields: No, I mean, it’s really moving, you know, because along with the level profile that started to follow you, your profile is rising. You are, you know, an an internationally known champion athlete becoming a multi-sport, um, athlete who’s, you know, like multi metal winning. That’s cuz I’ve

Oksana Masters: said it before, it’s totally, cuz I’m a Gemini.

I don’t know which one. If I want to be in the summer of the winter, which tan line I like. I like hot then I like being cold.

Jonathan Fields: Well, so you kind of like checked all the boxes there, so you, you don’t even have to choose it anymore, just like yes to all of it. But yeah, with so many more eyes on you, there are so many different ways to use that, um, that profile.

And you’ve chosen to use it in a way which just is deeply meaningful to you. And you’ve also really thought deeply about how you want your story to land and, and what is the message that, you know, you want to sort of like travel into people’s hearts and minds from that. And it’s a story of inclusion. At the end of the day.

It’s a story [00:51:00] not just of I’m exceptional in some particular way, or my story was like really rare and brutal in many ways. But you’re basically saying we’re all standing in the same tent. Mm-hmm. You know, and like, My struggle looks like this, yours looks like that. Yours looks like that. And a lot of people are gonna tell you no, or you can’t question that.

You know, just like, don’t just nod and say, yes, somebody else gets to set the constraints of my life. Question it all. Mm-hmm. That seems to me that is one of like the central messages that I see, not just in the way that you offer your message, but in the way that you live your life.

Oksana Masters: Yeah, absolutely. And I think what’s really important is I hope we all start to share.

All parts of our journeys. Not just the good days, but also just every aspect because we can learn from each of our journeys and what we learned and how, okay, well how did you get through this and how did you get through that? And it, that’s why it’s so important to share. We all have a story and I love the fact start line.

It [00:52:00] doesn’t care what you look like. Doesn’t care what background you come from. It doesn’t care what color you are, what language you speak, who you really are. It’s just a start line. And I think that’s like the best thing is like it’s become my metaphor of life. It’s just that like my, cuz sports is my d n A now.

But every time I think of a start line, it’s like no matter if it’s on a field, in a sport, on the water, on the road, anywhere, but or in business and the new goals, like nothing’s decided for you yet. You get to be in control of how you want this new journey to unfold. New whatever to unfold in. Yeah. I hope that it, I don’t, I’m pretty lucky that I’ve had the opportunity.

I know what it’s like to live out of a car, not have everything, no support to be at this place, to be able to bring awareness on inclusion, on diversity, resilience, and that we all can, we are all resilient. And also like one of my big [00:53:00] passions and motivators is to the younger girls, boys and girls, kids in general, but specifically girls, because I wasted so many.

Moments of my life and hours in the day of feeding into the energy of the voices that I heard of. My difference was bad. It was not good, and I should not dream or set goals for myself, and I wasted a lot of hours on that because I hated what I saw in the mirror. I believed everything that I heard, and it was just years through.

Learning and accepting. But if I can be one person that if a little kid sees me looking like them without their legs or sees that I’m different or sees that I’m doing a same sport as the athletes that we see on mainstream TV do doing, but I’m doing it in a different way, like then it will help them realize, wait a minute, like I can see this so I can do it too, and [00:54:00] they’re going to grow up with more confidence.

And instead of those years of. Not loving themselves, they’re gonna be the complete opposite and be like, watch me from day one and not needing to no longer say, watch

Jonathan Fields: me. Hmm. I love that. And it feels like a good place for us to come full circle in our conversation as well. So in this Container of Good Life project, if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Oksana Masters: Oh my gosh, I don’t know. So I think for me it’s like to live a good life is to embrace everything that makes you different. Just embracing, embracing every journey, every experience, every up and down. That is you are gonna live an amazing, good life if you just embrace everything life has to offer because those hard moments you feel like you might be in now, those moments will not always be your forever.

You always get to in a good life, just recreate that.

Jonathan Fields: Mm-hmm. Thank you. [00:55:00] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode, safe Bet. You’ll also love the conversation that we had with Kyle Bryant about how to transform physical challenge into action and a powerful reclamation of self. You’ll find a link to Kyle’s episode in the show notes.

And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did, since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor, a seven second favor and share it maybe on social or by text or by email, even just with one person.

Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those, you know, those you love, those you wanna help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more. Ease and more joy. Tell them to listen. Then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered.

Because when podcasts become conversations, and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive [00:56:00] together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields, signing off for Good Life Project.