When was the last time you felt truly at peace with yourself? Like you could look in the mirror or dip into your more personal thoughts and self-talk, and just know you were good. Like you embraced your body and your mind, in all their humanity, the state of your relationships, your health, career and life. No matter what was going on within you, or around you. And you were able to feel at peace with exactly who you are and are not, what you’ve accomplished and have yet to explore, and how you show up in the world?

When was the last time you felt truly at peace with yourself? Like you could look in the mirror or dip into your more personal thoughts and self-talk, and just know you were good. Like you embraced your body and your mind, in all their humanity, the state of your relationships, your health, career and life. No matter what was going on within you, or around you. And you were able to feel at peace with exactly who you are and are not, what you’ve accomplished and have yet to explore, and how you show up in the world?

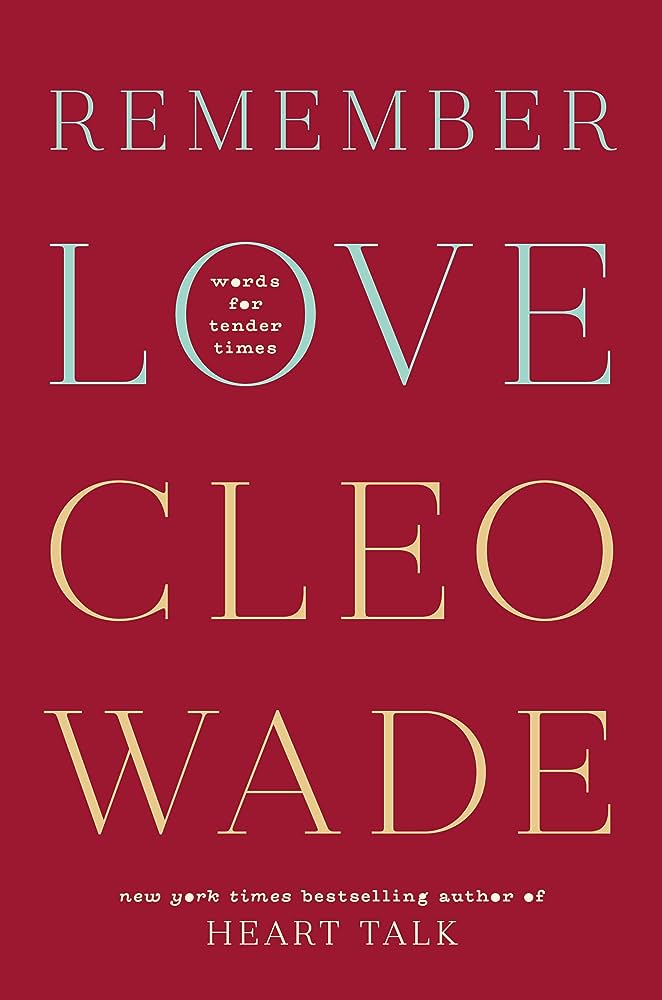

Getting to that place, for so many of us, is hard. But, my guest today, Cleo Wade, can help. Born and raised in New Orleans, Cleo’s writing and poetry have been a source of this kind of inner-kindness and self-forgiving and celebrating wisdom for me so many times over the years. She’s the New York Times–bestselling author of books like Heart Talk and Where to Begin, which share messages of hope, resilience, and the power of community.

Her newest, Remember Love: Words for Tender Times, could not come at a better moment. It is a collection of poems, essays, and inspiring words that invite us to embrace who we are and nurture our spirits during what she describes as tender times. The poignancy of Cleo’s words and observations have only deepened as she’s traversed her own transitions and struggles over the last handful of years, from becoming a new mom and finding her way through a brutal season of postpartum depression to navigating profound shifts in her relationships and identity.

In our conversation, Cleo and I explore how poetry can anchor us when we feel lost, the importance of tuning into our natural rhythms versus the frantic pace of technology, and how embracing life’s changes as natural allows us to grow through grief. For Cleo, it’s not about striving, it’s about accepting our own value as our birthright. It’s a homecoming. I know her words will stay with you long after this episode ends, reminding you of your own inner light. And, throughout our conversation, Cleo reads a number of deeply moving passages and poems that I know you’ll love.

You can find Cleo at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Sue Monk Kidd about life transitions and changing lanes.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- My New Book Sparked

- My New Podcast SPARKED. To submit your “moment & question” for consideration to be on the show go to sparketype.com/submit.

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Cleo Wade: [00:00:00] If you do not have some relationship with looking at yourself every day and saying that was enough. You did your best and it was enough. Then you live as a disappointment every moment of your life because nothing feels like enough ever. That is so not our natural nature.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:20] So a question for you. When was the last time you felt truly at peace with yourself? Like you could look in the mirror or dip into your more personal thoughts and self-talk and just kind of know you were good. Like you embraced your body and your mind in all their humanity. The state of your relationships, your health, your career, your life, no matter what was going on within you or around you, and you were just able to feel at peace with exactly who you are and are not what you’ve accomplished and have yet to explore, and how you show up in the world. Getting to that place for so many of us is just so hard. But my guest today, Cleo Wade, can help. Born and raised in New Orleans. Cleo’s writing and poetry have been a source of this kind of inner kindness and self-forgiving and celebrating wisdom for me and for so many over so many years. She’s the New York Times bestselling author of books like Heart Talk and Where to Begin, which share messages of hope and resilience and the power of community. Her newest, Remember Love Words for Tender Times could not come at a better time. It’s a collection of poems and essays and inspiring words that invite us to embrace who we are and nurture our spirits. In what she describes as tender times and the poignancy of Cleo’s words and observations have really only deepened as she’s traversed her own transitions and struggles over the last handful of years, from becoming a new mom and finding her way through a brutal season of postpartum depression to navigating profound shifts in her relationships and identity.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:55] And in our conversation, Cleo and I explore how poetry can anchor us when we feel lost. We look at the importance of tuning into our natural rhythms, versus the frantic pace of technology, and how embracing life’s changes as natural allows us to grow through grief. And for Cleo, it’s really it’s just not about striving. It’s about accepting our own value as a birthright. It’s a homecoming. I know her words will stay with you long after this conversation ends, reminding you of your own inner light. And throughout our conversation, Cleo reads a number of deeply moving passages and poems that I know you really love and you may even return to listen to over and over again. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life project. I love the opening idea also that the name of the book is Remember Love, and it comes from an experience that you had with listening to Tara Brack, who, like you and I, are these long-time, sort of like long-distance devotees of Tara and her work. I was wondering, because I feel like it really sets the tone for the book. I don’t know if you have a copy of it with you, I do. Would you mind actually just reading like on page eight, like those couple of pages that open it? Because I feel like it just gives such beautiful context to the rest of the work.

Cleo Wade: [00:03:17] Yes. And you know what’s cool? I’ve never read this out loud. I know how to love myself on a regular day. Feeling like my regular self. Nothing really prepares you for how to feel good about yourself when you don’t feel like yourself. This hard to love a stranger. It is extra hard when change has turned you into the stranger. Lying awake in the night. My racing heart grabbed my inner megaphone and repeated the words, something is wrong with you so loudly it echoed through my bones. It was a lie that felt true and I couldn’t unhear it. Self-love is often spoken about like a battle. We either win or lose, but it manifests more as a bird in flight. It is minute-to-minute. There are moments we glide through the sky, riding the wind with ease, and there are moments we must exhaust our wings to survive the elements. On my worst days I forgot I had wings. I believed every negative thing I thought, whether it made sense or not. In hopes of finding a little comfort during my tough time, I ran a bath one night and put on a talk by Tara Brack, a meditation teacher and psychologist. I have listened to for over a decade.

Cleo Wade: [00:04:31] As I sat staring at the ceiling for half an hour, kind of listening, kind of not I heard two words that jolted me from the haze of my brain fog. Remember love. It was as if she had not said a single word. Except these the past 30 minutes. Remember, love. I write because I know the power of words. Words have saved me every time I needed saving. These two words did something to me. They say to me. I began to ask myself if I could remember. Love and life changes. Can I remember love? Can I change? Can I remember love? My relationships change? Can I remember love? When I remember love, I remember I am resilient. I can love myself through a hard time. I know this because I have done it. I remember that my spirit is soft but durable. I remember that my love belongs to me when I am at my sturdiest and my most fragile. I remember that my life is bigger than whatever noise surrounds me. I remember that clear days have always followed my storms, even when the storms felt like hurricanes. I remember love and I remember my wings. I remember I can fly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:50] So beautiful. Thank you. It’s interesting because the word remember is really important in that because it’s not about finding. It’s not about seeking. It’s not about creating. You’re signifying. You’re saying no, it’s actually this has been a part of you, you know, for Time Immortal. And it’s about reconnecting with that. And I love that frame because it’s different. It’s less of a striving and more of a being.

Cleo Wade: [00:06:17] I think also, you know, so much of this book is about this return to self, this idea that love is our love for our self is our birthright. It just is. And knowing that is so critical. And this was the first book I’d written since having children. And something I noticed as a parent is when you watch your child from zero to, I now have a three and a half and I have a second child who’s two. When I watch them, they love themselves with ease, they love themselves and they are four months old and they’re chewing on their own toe. They delight in themselves when they have their quirky outfits on, that are inside out and stomping in a puddle. They do not think anything is wrong with who they are. They love themselves. And that was such a the observation of that. Because though I’d spent time with children so much in my life, I. There’s nothing quite like living day-to-day with a child. There’s a really intimate understanding in how you observe them if you’re watching. And it was so clear to me and so confirmed, which is also an idea that helped me when I was going through postpartum depression, that the love was there. I had to. I knew I at least knew what I was getting back to. I knew I was going back to something that was already there, that already belonged to me. So it was just something that I had and couldn’t access. It wasn’t something that I where would I find it? Is it a possibility? Do I know if I have it or not? I knew it was there because I saw it be born in my own daughters.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:58] It’s funny. I remember as you’re speaking, I’m having I just had this momentary flashback of probably 20 years ago, a conversation I had with David Crosby where he was saying that he learned more about life back then, spending 15 minutes watching his toddlers play than he did 15 years studying with a guru. And I think when you’re really paying attention, you see so much of what we aspire to grow into and to achieve and to become as adults is a returning to that state that we started out at, you know, and it’s sort of like so much of it is just allowing rather than aspiring.

Cleo Wade: [00:08:37] And the palm either right before those pages are right after is called homecoming. And it was the first poem that I’d written for when I knew I was writing this book. And it was this idea that, you know, we through neglect, we find this disconnection, you know, and we neglect ourselves often because life happens and change happens, and it makes us different. And when we’re different and behaving differently, we usually are like, what’s wrong with me? What’s wrong with me? What’s wrong with me? Rather than saying, okay, you’re different, what do you need? And today is different. What do you need if you live in wherever you live and the sun is out and you say the sun is out. Okay, what do you need? Sunscreen. Okay. It’s raining. It’s raining today. What do you need? It’s the days are different and the day is still the day. And each day is different. What do you need is actually the question that allows for us to give care with flow every day.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:36] I wonder if we sometimes ask that more of others than ourselves. Do you have any sense of that?

Cleo Wade: [00:09:42] I think when we are in service of others, we receive affirmation of being helpful in any type of affirmation. Feels like love because so many of us we want soothing. We all want to be cuddled and nurtured and soothed, which is why we look for things to self-soothe that are, you know, far outside and not sustainable. And we look for it in relationships. And so we think oftentimes we’re very good at attuning to other’s needs, because at some point in some way, we get a reaction from them that says, you are lovable, you’re good, you’re right. And we don’t often have that type of dialogue with ourselves within. You’re not like, oh, that was great of you. Good job you did it. We usually hear that you’re not enough. That’s not enough. That was good. But what about this? And everyone liked it except that one person or you know. And so I think that kind of inner environment isn’t one affirmation of goodness. Fundamental goodness is as present.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:49] Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Part of the early part of what you just shared. Also what the reading that opens the book or sort of like shares how the book’s name came to be. You know, the early part of that is also how do we learn, remember to love ourselves when we feel like we’ve become a stranger to ourselves, when we can’t actually even recall who we are? Like, we don’t know who the being is anymore. That we would remember to love and feel like. So many times that happens when we become adults, when we become parents, you know, we hear so many folks say, I’ve lost my sense of self, my identity, and it’s hard to know where to direct that feeling when you can’t even remember who to direct it to.

Cleo Wade: [00:11:25] Yeah. And I think that’s where what you need becomes fundamental. Because when you feel like so much of what creates this or feeds that feeling of being a stranger and was really specific with the words in that sentence where he said, when change turns the stranger into you, you know, because there is every time you feel like a stranger, you will find that change was happening somewhere. And change is life. And we need change, and change is growth. And you know, we need those moments of feeling like a stranger because they lead to incredible moments of contemplation and intention, setting and asking for help and seeing which hands are helpful hands in your lives and which are not. So these these moments are critical to our evolution. And I think so much of what deepens the hole of feeling like the stranger is you just keep trying to treat that person like the person you felt like before. And so, so much of when I was even writing about recalling that story of putting on getting in the bath to listen to Tara Brock was saying that when I talk about this, because I haven’t read that passage before, but I talked about it on my tour, is that I just kept doing all the things that should have worked when felt like myself, but I wasn’t myself. I was someone who has lived through or was living through a past, a global pandemic, sending everyone inside.

Cleo Wade: [00:12:52] And I’d had two kids and I lived in a different city, and I had so many things that were different. And so why would I feel if I have self care is a tool kit, why any of the tools in that tool kit would function for a completely different person. And so even I started to pause and say, okay, like what is the first thing I could do to help? Okay, a bath has always made me feel better. But you know, I’d say ten years ago a bath would have been my solution to a hard day. If I put on a bath and got in the bath, with Tara Brach. I’d actually be hanging on to every word, and I’d get out and I’d go to bed, and the next day I would have said, I alchemized the experiences and day of yesterday and I could start fresh. And I feel better when those things are working. That’s when it’s time to say, okay, what’s going on? Do you know what? What do you need? Because, you know, try with the stuff you do know that helps. And when it’s not helping, are you just trying to give someone who needs to now be a vegetarian like a big steak and, you know.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:56] Yeah, it’s sort of like, is it that the tools are failing or that I’m just different and it’s time to sort of evolve. The tools evolve the way I’m thinking about it or stepping into it.

Cleo Wade: [00:14:05] Change the tools. And that’s why it’s so important to have discipline in the sense that care is always there. And the discipline about putting ourselves on the map in our life and where we need fluidity and flexibility is what does it look like? So really it’s like, give yourself two hours and doesn’t it mean it’s a block of two hours? But give yourself throughout the day, 30 minutes here, 30 minutes there, 30 minutes there and there. Care comes in hard. Let it look different. Maybe it’s a walk. Maybe it’s just moments with your favorite song and silence. And no one’s really allowed to talk to you. Maybe it’s this, whatever it is, but have the discipline around the presence of care. And as you change and as you grow and you go through and what you need, let what the care looks like shift and change.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:56] Yeah. It’s interesting, the opening line and I’ve heard you share variations of this poetry is my therapy before. I can’t afford a therapist, which is funny. And also like there’s a lot of truth in that, right? Yeah. Do you feel like. Because what I’m wondering is, are there things that have been a go-to for you or no matter who you are or what you become, what place in your life? There are these three lines because it feels like for you poetry. It feels like in conversations we’ve had in the past, also music, art. These are not just forms of expression for you, but they’re forms of reconnection, remembering, of solace that keep coming back to you and that you keep returning to. And maybe expression is solace for a lot of people.

Cleo Wade: [00:15:40] You know, I think you have to always ask. Yourself, and I certainly do. What in my life do I know for sure? Is a life-affirming like that just brings out your aliveness and makes you happy to be alive. And I know we joke about my obsession with Jazz Fest, which is very real. And I’ll also tell you that last two Jazz Fest ago, I was coming out of the depths of my postpartum depression with Bayou, and it was I was phasing out, you know, because obviously you have not been pregnant before, but it does, you know, turns into something else, but it does not stay at the P it is so chemical that it does. And so it was kind of ending and I was on the fence. Do I go to Jazz Fest, do I not, because I was just kind of feeling really lethargic and a bunch of my girlfriends that I go with all the time said, you’re going. And as I planned it, I said, okay, you know what? I’m going to bring even my kids with me. And but in my kind of self-care, I said, okay, I’m going to put my kids hanging out at my mom’s house. I’m going to stay at the hotel where all of my girlfriends are. And I went to Jazz Fest. I went every day and it felt like, you know, Jazz Fest is not a silent retreat or like a yoga retreat.

Cleo Wade: [00:17:01] It is like you are just drinking beer and you’re hot and you’re sweaty and you’re on the bike and you’re eating red beans and rice, and it’s a really it’s a if for some people it’d probably be an unenjoyable experience. There’s a lot of elements. It’s a lot going on. The sun is beating. You can like barely want to wear clothes. You’re sweating so much. And as I was there by the end of day three, I was I was called on to remember, oh, this is life-affirming. I’ve been going to this every year since I was in my mom’s wound. I miss Jazz Fest. One time I remember this is what’s so important. And then it was really crazy because right after that, I remember calling Simon and I was like, you know what? I think I’m going to take the girls because we’re already in the South. I’m going to take them to the beach for a couple of days before we come home, because the one kind of trick about having moved to LA is that LA was like a cold time once I moved here. And so this, like LA’s got the perfect weather and it’s so warm was not real for me. And so I go and I sit on a really, really hot beach in the South, and I remember that I was like, God, I just needed cold water and warm sand.

Cleo Wade: [00:18:11] And I went for two days. And then we came home and I was really revitalized, not because I’d had green juice every day or meditated every day, or did yoga every day, or all of those different things that are also amazing and very like, affirming. But I soaked in what I feel is the juiciness of the human experience, which is being in community and enjoying our in a really immersive way, eating food that is so is cared for and prepared with such love and tenderness and soul, and being with people who are truly there to have fun, a fun-loving environment. And it completely shifted me into a new space. And so every time I think about that, since that period of time, you know, two years later, whenever feel a little funky, I’m always like, well, where is the concert I need to go to? Or who’s the friend I haven’t had dinner with? Where’s the life-affirming thing? That is not going to be the kind of quintessential self-care tool, and it’s not necessarily the Tara Brach, which is also helpful, but it’s the thing that helps get you out of your head and into aliveness and out of the constant even thinking or feeling space and into the like being in it. Presence of experience. That has been a real incredible addition to the ways in which I give my self-care.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:34] I love that reframe the question what makes me feel alive? It’s such an alive question because instead of saying like, you know, like which of the self-care things on my checklist should I be doing today? Because I’m feeling like I need something? That’s a fairly limited question, because most of us have like, this predefined list of things that qualify as self-care. But if you’re like, what makes me feel alive? It could be death metal. It could be like, whatever it is for you, you know?

Cleo Wade: [00:19:59] And there’s a moment in which you have to befriend yourself to answer it. Yeah. And that’s important because only that’s such a question. Only a friend would ask you, like, let’s do something fun tonight. What should it be? The way that you could ask yourself that is to immediately befriend yourself. So you’re already starting with the kind of juicy pulse. And so in that to then say, oh, it is such a nice day, I’m going to just go towards the sun. I’m putting on my sneakers, I’m just going to go on a walk, even if it’s just for 15 minutes. And that just to be in nature and notice aliveness made me feel alive and sure that it could mean I didn’t do the. Whatever the things that I are on this should-a self-care list. Where’s the how are we finding harmony in the should-a and the wow. Oh my gosh, that awe the list of things that leave us in awe or leave us in laughter. Because especially when the world feels so consistently harsh, those spaces of just, you know, that kind of Mary Oliver joy, is that meant to be a crumb so important?

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:14] So agree. Especially as you described now when the world is so full of harshness, you know, the subtitle of your book really references the experience of tenderness. You know, which who is not feeling that on some level these days, you open your eyes and you’re like, it’s there. You move through the day. It’s there. You put your head on the pillow at night, it’s there and you kind of know it’s coming back the next morning. So being able to ask these questions, which let us reconnect, and also knowing it doesn’t have to be these big momentous things, it could be these like tiny little things that just reconnect us. You also, suddenly you brought in this notion of and this is where you sort of like really refocus the energy in your writing and around the notion of enoughness basically straight up saying, well, this is actually a mirage. And so many of us aspire to some version of not even just ourselves, but of life. That is quote there we finally made it. And the idea of letting that go on the one hand is unmooring, but on the other hand is forgiving and space-creating in a lot of ways.

Cleo Wade: [00:22:24] I think the poem on that page says something like Enoughness is not a mountain, it is a mirage of a mountain. We don’t need to climb it. We need to see through it. There’s so much suffering we have because we cannot say. And that was enough, because we live in a world that functions on crippling us with not enoughness, because then we want the car, we want the house, or we want the thing, and we walk the want, the want, the want the, you know, every day say to my, my three and a half-year-old, you know, there there’s that phase of learning language. She’s like, I want a tree and I want to like. And I was like, I was like, no, not with the I want. What’s with the. I was like, it’s like I can’t feed into the I want energy. Talk to me. Can I have. What are you thinking? What are you feeling? You know the I want. This even starts so early I want this, I want that, I see that, I want that, and I think for me, as somebody who recovers as a perfectionist, recovers as a chronic doer, all of those things are fueled by not-enoughness. You know, even said to someone recently about someone who is kind of kind of ended up in some type of situation with like some kind of like scandal, not stealing money, but something like that.

Cleo Wade: [00:23:46] And I remember saying to someone who was friends with the person, I said, you know, what are you talk to about them with them? And they’re like, oh, they just talk about why it parts of it was wrong or right or this or that. And I said, but is there this conversation with Enoughness? Can we start with where we are and who we are is already enough, so I don’t have to think about maybe taking investment from a strange space or a do you know what I mean? I can just say, how do I find okayness in Enoughness where I am that. I can maintain the highest possible integrity of how I build and do or create the life I live in, and that is just the last thing on the list of how we conversate. I think now, and I think for me where I bumped up to it against bumped up to it most personally was in motherhood and parenthood. Because if you do not have some relationship with looking at yourself every day and saying that was enough. You did your best and it was enough, then you live as a disappointment every moment of your life because nothing feels like enough for parenting. Nothing makes you feel like you did enough for your child that day, ever.

Cleo Wade: [00:25:01] And there’s no way to do it all. And no matter what you do, if you do it all, you can have the day where you did the pickup and you did the drop off, and you did the day and you did it, and you, you made sure everyone got their lunch and you cooked the dinner, and then it lands on the table, and they don’t like what you made them like, so. And that’s life. And every space you could say, you know, you make the book and you did. You did it. And you read the book in front of the crowd of people. And then there’s the one person who fell asleep that like, but in the conversation has to say it was enough that I could read a book in public that was my own writing. And it’s enough that I get to read words I love. And that is combating this nature, this kind of public atmosphere that becomes our nature, that is so not our natural nature, because no tree does not think it’s enough, and no river does not think it’s enough, ever. And that is so much more natural rhythm than, you know, whatever social media is telling us or a billboard is telling us, and building this ecosystem of not enoughness. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:07] And so agree. And on some days just showing up is enough. That’s what we have in ourselves, you know, like no matter what we think is expected or demanded, like that’s what we’ve got to give. But it is really hard to make peace with that, I think, because there’s so many external pressures and expectations and societal norms that kind of, say, familial norms that say, well, that’s actually not okay. So we have to make peace with our own definition of what is okay. Something you wrote in, I think kind of speaks to this really nicely. Also, I’d love to ask you to read this to page 61 starts out, why do we wait to love ourselves?

Cleo Wade: [00:26:45] Why do we wait to love ourselves? Can we love ourselves without feeling like we need to be right, perfect or good? Can we love ourselves whether or not we have the right job, car, house, body, fat percentage, relationship or family? Like we don’t need to earn our own love. It is our birthright. It wholly belongs to us, no matter our circumstances. External validations don’t lead us closer to love. We lead ourselves closer to love. It is within us. We connect to it by going inward. Love waits within. She is like a favorite auntie. Whether you haven’t seen her in a day or a year, she opens her arms to you for a big hug and says okay, tell me everything. Know how easily and quickly we get disconnected from love. We feel sad, anxious or depressed is hard to locate, love beneath our symptoms. There have been times over the past couple of years when I thought if I could just feel less tired, or if my brain fog would just dissolve and I could feel okay with myself. And I could love myself. I’d forgotten that it is in those moments I need my own love the most. The truth is, we need our love every day, regardless of how insecure we may feel. It is our stabilizing force. We think we always have to be more in order to be loved. We will never be able to accept love, not from ourselves or anyone else. You already deserve to love and respect yourself. Befriend yourself. Love who you are today, no matter what it looks like.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:32] I love the imagery of the favorite Auntie.

Cleo Wade: [00:28:34] Yeah. Me too. As I was reading it, you just.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:36] Feel like there’s a warm hug as soon as like, everyone’s going to bring their own visual of that to it. Yeah. And then to sort of imagine that, you know, she resides within us, not outside of us. Yes, it’s great to get that hug, but also we always have the capacity to give that to ourselves. I think is a real shift in perspective, too, because so often we’re just looking for it on the outside rather than trying to find it on the inside. And then we basically give away a sense of agency around it by doing that.

Cleo Wade: [00:29:06] Yeah, we need to. Or when we, you know, there’s another page that’s kind of near that, that where I talk about when the material is at the center of my gold, even when I cross the, the finish line and, and hop the gold medal, there’s some loneliness there. But when the relational is at the center of my goals, I’m holding the gold medal or not, whether I was first or last, I am what’s held at the end. And I think today’s world, especially when we’re living in so much isolation and we’re still very disconnected as a community from being indoors and living, and I think especially in America through our last elections, and we aren’t centering the relational and that includes the relationship with ourselves. And so this idea that every day you can say you have the power to say to yourself, what would make me feel loved? How can I be loving? And then I work backwards from how to make the day, create the day from that, rather than saying, what can I do that would make me deserve love? Like, you know, like instead it’s like I start like love. I don’t have to earn it. It just what excites it within me. What gives me time or space more? Is it that I end of the day at a certain time? Because that means I got to watch that movie on the couch with my kids. Does it mean I got the walk-in? Does it mean I put my favourite song on and dance by myself in the kitchen as I chop the onions, whatever it might be? But what are those things that are the collection of the small moments where just love is present and there and easefull and the day lead to those moments. The ability for us to have those moments be the goal of whether or not we were successful, that we were proud of who we were because of the joy we found rather than what we may did, or the gold medal being around our neck.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:11] Yeah, that resonates so deeply. I think it also brings in the notion of timing and seasons which again, these are things that you write about and that you speak to, you know, and really internalizing that too, and saying like, there are no sort of like timeline that I need to aspire to feel this way or to get to this place. And also acknowledging the fact that we have seasons in our lives that bring us different things, where different feelings, different experiences are more or less available to us. And rather than trying to abide by somebody else’s timeline or force us to be into a season that we’re not like, what would happen if we own that? And then really inquired, what do we need in this space? If we accept where we are on our own timeline?

Cleo Wade: [00:31:54] And to recognize that it’s not seasons of life aren’t just, you know, the winter of your life is not just when you’re older. It’s that in a single moment of your life, you could just be in a winter. And maybe the disconnect between you and your partner is that there is spring and you’re in a winter, and that’s what’s really hard, and that both of those seasons need different things, and that all of these seasons have a completely different energy. You know, there’s and it’s so amazing to have these kind of summery seasons where, oh, it’s just joy and it’s fun and it’s the sun and relaxation is at the center. And then there’s winters that where you’re just, just got to get cozy. And I’ve just got to protect myself and feel like I’ve just got to get through and wait till it’s over. And there’s these springs of of just new ideas and doing and motion and dreaming and going. And there’s these fall seasons of just letting go and grieving and contemplating and thinking. And so I think when we realize that those seasons flow through us very regularly, not like, oh, I’m a spring chicken. It’s the spring of my life when I’m this age.

Cleo Wade: [00:33:08] And it’s that. It’s like what any given time we reflect on what season you feel that you’re in because you know, so much of my hope in writing, remember love, was that we could find this natural rhythm so that we would stop. Trying to find a rhythm with our the world of technology. And I’m not a person who, you know, don’t hate technology. And I think it’s a remarkable tool and can be so powerful and useful. But something that has happened is because we are so deeply connected to a robot or device or computer being in our hands at all times, we have started to believe that our rhythm is its rhythm. And if your phone is moving more slowly, you think something’s wrong with it. You banging it around, you’re like, I’ve got to take this phone in. It’s just, this app takes forever to load this dadada. If you are moving more slowly, you likely just need to be moving more slowly. There’s nothing wrong with you. You are not broken. You are not needed being fixed. We have seasons where our body’s natural flow is saying move more slowly. I am trying to sustain a life here that is never what is going on.

Cleo Wade: [00:34:24] When your phone is going to be more slowly, it is saying that you know, if I walk down my canyon at one point of the year, there is no stream that goes beneath my this kind of ridge by my neighbor’s house. And then at other times it’s a flowing stream and sometimes there are some rainy seasons. It’s really high, and that is just what it is. And we don’t even need to overthink it. It is what it is. And certainly the stream is not thinking anything about itself. And so that’s why I try to write my books. Anyways, I hope that people can just reclaim themselves out of these rhythms that just don’t serve us. They’re not the worst things in the world, but if we want to stabilize, if we want to connect with ourselves, if we want to reap the benefits of knowing love of self and care of self, you have to be in a rhythm where those things can actually flow, and you can hear yourself without the false judgment of your computer that’s malfunctioning. You’re not malfunctioning. You just need different things. You need to move slowly. That is being a human being.

Speaker3: [00:35:34] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:35] And I feel like a big part of that is our capacity to be present with whatever’s going on and how things are. We don’t we can’t own the fact that we’re out of sync with some sort of rhythm that’s intrinsic to us, until we actually notice that there’s something out of sync and we kind of say, huh, is this okay? Is this a time for me to actually just pause for a minute, see how I’m feeling, and see, like, is there a season or a rhythm or a pace that just feels more intrinsically mine at this point where I can step back into myself, I can remember myself. I can be and feel the way that I want to feel. You know, part of the thing that I think kind of knocks us out of those things sometimes, and again, this is something you write too, is is the experience of loss, the experience of heartbreak, and certainly with the state of the world for the last three, four years. And currently there is loss. There is heartbreak on every level. You know, whether it is immediate heartbreak of somebody individual in life or just on a global scale, you pose a really interesting question. One of the essays, which is are things falling apart or are they falling away? I was curious what was going through your mind as you sort of posited that question.

Cleo Wade: [00:36:48] Over the last few years, what was moving to Los Angeles and just in general was having personally having what knew a lot of people could relate to this, this idea of your friends feel kind of unfamiliar to you, or you’re needing a change or you’re not, you know, you’re having some kind of shifts where, you know, maybe friendship breakups are present or things like that. But I didn’t feel this kind of loss or conflict. It felt like almost a natural shedding skin. And again, I don’t think a snake ever thinks about its skin shedding. I just I just don’t think it keeps moving and sees that as a part of its life. And I really considered I could frame this as, what’s wrong with you? You don’t like the same people, or this used to be fun to you, or this isn’t or this is dadada. Instead, I just leaned into this idea that I’m a natural growing thing that sheds and things fall away, and there’s an everydayness of grief that exists in the human experience. And I can allow that to be a very regular part of aliveness. That was a really big aha for me, because I think oftentimes when we’re going through big changes that change how we socialize or, you know, there’s another page of the book that says, you know, you’re social circles aren’t necessarily your healing circles. You know, you really you have guilt and it creates a drama because somehow it’s like if. Were wrong or you were right or this was bad. And you know, we want to give everyone a character as if life is this constant play. And we need to be rooting for someone all the time, or we have to be, you know, in our own kind of personal inner Justice League.

Cleo Wade: [00:38:41] Um, and I remember, you know, I didn’t have it at the time, but as I really thought about that time and how I wanted to alchemize having experienced that and, you know, in heart talk, I think this is in heart talk, but there’s a page that says, um, your life experiences are only as valuable as your ability to turn them into life lessons. And so, you know, a lot of my writing is not necessarily that I had some kind of guru like moment where I got it right at the time I didn’t, but if I don’t feel I’m getting it right, or I didn’t feel that, if I felt that I experienced something that I think a lot of people experience in my head. Space is really frenzied. I usually take years of considering why it was and how it could have been, what mind frame would have made it different. So when I did that, for that shift of life, I thought, gosh, you know, grief is every day, shutting is every day. We don’t need to overthink it. We don’t need to dramatize it. We just need our own clarity, our own honesty, and to wrap the situation and love and integrity, even if love is a boundary that disappoints someone. But that’s boundaries. And do that all the time, unfortunately. And so. But as long as it’s honest and it’s true to you, and it’s done lovingly and with clarity, then it is what it is. And so I think there’s a poem mirrored those pages that say it bes this way. Sometimes it’s just a saying. My dad always says it’s like it’s really kind of stepping into the old mantra of it is what it is.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:19] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:22] There’s another poem actually in that section. I’d love to ask you to read it. Page 128 Heart. Mind. Body.

Cleo Wade: [00:40:28] I love this poem.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:29] Yeah, Me too.

Cleo Wade: [00:40:30] This was the last poem that was added to the book. Heart, mind, body. We cannot only build empires. We must build homes. Places our eyes can close. And find warmth by the fire. Our hearts cannot survive in skyscrapers. Our hearts want to leave their shoes at the door of a nearby forest and follow the trail. Our hearts want to feel the hum of the hummingbird. In the busy mind. It needs sun and sky. It begs to hear the nearby stream wash over its endless thoughts. Of course. I cannot forget the body. It told me to tell you. It would like to dance and run free. Also a kindly requested a quiet squeeze and an I love you. As soon as you get a chance. Love that poem so much.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:31] So do I. It’s like a giant exhale.

Cleo Wade: [00:41:35] And it’s a re. It’s a different rhythm. Yeah. And so much of what I hoped with this book specifically was that it could invite us into a different rhythm, because the rhythm that floods us currently in our devices is unhelpful, I find. And when it’s not deeply boundaried. And so if we are going to allow the kind of, you know, our phones to tell us what our rhythm should be, that I guess, is what I’d say is unhelpful and so, so much. And I wanted to do this with The Remember Love because Mary Oliver did that for me. I have anxiety, and she invited me into a different rhythm when I read her work. And that was life changing for me, was my therapy before I could afford therapy. That’s Lucille Clifton’s work invited me into a new rhythm. Even Toni Morrison’s work of fiction invites you into a new rhythm. The way that she writes is so it’s almost like a different language, that it takes you the first 50 pages to even drop in, because she’s saying, come into this world and you have to become immersed to get in there and really feel the depths of her experience. And Nora Ephron did that. Does that. You know, when you read heartburn, it invites you into a radically different rhythm of this fun, observant, you know, quirky way of feeling and looking at the world, this personality. And and I’m so grateful to all of those writers, but especially Mary Oliver, because you felt that every day she took you on her walk in the woods and you felt the healing it gave her through her words. And even if you didn’t have access to a walk in the woods like me, a little girl in New Orleans who moved to New York City, I didn’t start going on walks in the woods until five years ago, so I feel so lucky that I got to do that through her words, because I reaped the benefits of her healing journey because of it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:57] Yeah, one of the I think the powerful elements of verse versus prose, not that you can’t be moved to a different rhythm by both, but I feel like verse is often so different than our standard, our everyday rhythm. Even like what we read, what we see, what we consume in all forms of media. It’s a pattern interrupt. It is. It forces you to experience it at a different pace, a different cadence, a different rhythm. It’s like it makes your mind, your brain, your body just it forces you to shift gears like you can’t blast through it. Yeah, it’s.

Cleo Wade: [00:44:31] An invitation to drop in. I think that’s why if you go to a yoga class or something and you’re doing your savasana at the end, they’re likely reading you a poem at the end and they’re reading Rumi, or they’re reading Hafez, or they’re reading a Mary Oliver poem or Maya Angelou. And because as you are getting to the core of this relaxed mode, they’re giving you almost like a mantra to hold on to, to maintain that feeling you had at the end of that class. So you have those words to take with you that remind you of the possibilities of where your nervous system can be from that day.

Speaker3: [00:45:11] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:12] And part of that is being willing to let go of where it has been and where it is right in that moment. And this is sort of where you bring the book home also. This is where you’re like, okay, so let’s talk about this experience of letting go. And as part of that, starting over, one of the early essays in that part of the book starts starting over as a part of our nature. And it’s really about what if new beginnings were actually not something to be terrified of, but were something that were filled with possibility and also natural that you actually can’t avoid, you know? So rather than stopping them from happening, what if we welcome them and look for the spaciousness and the possibility within them? I love that you sort of invite us into inquiry.

Speaker3: [00:45:52] Yeah.

Cleo Wade: [00:45:52] And again, it’s cutting or weaving grief into life as an everyday thing. You know, even having, um, I think having children so small and feel really lucky because have a lot of girlfriends who had kids before I did that are now teens and in their 20s. And so, you know, you really got a lot of the talking to, like, it goes by so fast or into today. And it does. And I’ll say that because I have such an intention around the everydayness of grieving two and a half to three to to this smallness, to this size, I feel very present in where they are. Whereas I do feel that a lot of the times we are so avoidant. Of the grief of life beginning and changing and being different every day, and the growing. Up ness of ourselves and our loved ones and our children. The avoidance, as I think often what makes it feel like, oh my God, it just happened. Where did it go? And to me, this idea that we can just again, whether it’s the shedding, whether it’s the new day, all of these very natural ideas allowing them to be this everyday way of looking at life, which is what, you know, the Buddha is doing, you know, is doing it. And every spiritualist will tell you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:16] For a few thousand years, a few.

Cleo Wade: [00:47:18] Thousand years, or, you know, my dad in New Orleans who say it bes that way like it is what it is, and today is what it is, and the childhood only went by too far. If I am avoiding the grief of, you know, or stuck in the past of who they once were and how I felt when they were, that versus how I feel with who they are today. And but if I just am in it is what it is, and the sun is going to go down and the sun’s going to come up and it be that way, I mean, to embody that moment to moment feels really scary. But it’s actually an incredibly calming experience because you do allow yourself to be, observe, feel. And to me, it’s been more of a it’s been a helpful way to even cope. You know, it’s this way of having an inhale and an exhale of these, you know, whether it’s the atrocities of our world or, you know, our neighborhoods or whatever goes on to just say, you know, and not without compassion and not without empathy and not without all of the very alive and important parts, fundamental parts of who we are that our world so desperately needs. But to say, okay, this is what it is. How can I be helpful? Obviously, we want to be these, you know, I always say, like the kind of Mr. Rogers, find the helpers, be the we find the helpers often by being the helpers. And so, you know, we want to help. And how can I be of service and what can I do? But the ways in which to cope with these very particular times of life have been here for for thousands of years, you know. And it has it is through presence. It is through service. It is through gratitude. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel on coping with and still be a loving person in a broken world.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:23] Yeah. It’s like one of the earlier poems in the book where you write present. Here I am. Like, we’re trying to get back to that place. Yes, I would love if you’re up for it. As we sort of come full circle in our conversation, is there one poem that you feel inspired to sort of like close out our conversation with?

Cleo Wade: [00:49:43] Mmmmmmm. Okay, let me see if I can find it. You know, I didn’t have, like, a I didn’t have a hard copy of this book for so long. And so I had this PDF. Um. This is called how it goes. It’s been raining and raining and raining and raining. It rained so much it felt like it would rain forever. And one day. At 5:30 p.m., abruptly, with no notice at all. The sky was dry, clear hot pink and orange. There was even a little purple woman in. That’s what it’s like, isn’t it? Your heart is broken and every day is sad. Until one day, all at once with no notice. You find beauty again?

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:31] Mm. Thank you.

Cleo Wade: [00:50:32] I left that one when I first wrote it. I thought of how it feels when you’re going through a relationship breakup. And then as I read it on my tour, most people experienced it with their grief. And I didn’t realize that I didn’t, um, it was, um, you know, something I’ve always felt so grateful about and over the years with my work is that, you know, you have something and it’ll resonate with somebody who was a teenager and someone who’s 75 who were going through radically different things. And you’re like, how wild that this, you know, and that’s always my goal is that how can it be wide enough but feel intimate enough that it can serve you no matter who you are and what you’re going through, but not be so wide? It feels like it’s for no one. But it could also be for anyone. And it always surprises me when that happens. That how I wrote it takes on a wildly different life than what it meant for me when I wrote it.

Speaker3: [00:51:35] So yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:36] No, I love that too. Good place for us to come full circle. So in this container of a good life project, if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Cleo Wade: [00:51:45] To live a good life is possible. When you prioritize having a life. And allowing a life that has real aliveness. This idea that you can have a good life when you want life. You want a live life. Juicy squeezy. Amazing. You know that kind of. You’re not looking for the things that make life this labor and obligation after another. After today you say gosh, life today full. Wow. All that hope for yourself or way to orient that. If you can orient your life towards that goal, a good life that I believe is very possible.

Speaker3: [00:52:35] Thank you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:38] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode safe bet you’ll also love the conversation we had with Sue Monk Kidd about life transitions and changing lanes. You’ll find a link to Sue’s episode in the show. Notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me. Jonathan Fields. Thanks to Alejandro Ramirez for editing on this episode. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor, a seven-second favor, and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.