Have you ever felt like your mood, energy, and cravings seem out of your control? That no matter what you do, you can’t escape that afternoon slump or those intense sugar cravings that hijack your willpower? For me, it hits right around 4pm, and the cravings can feel relentless. But it’s not just the ravenous urges that are the problem, it’s the changes in physiology that underlie them, and all the other ways those changes impact our physical and mental health. And, the way they drive us to eat things that make the problem so much worse and send us into a blood-sugar-driven spiral of doom.

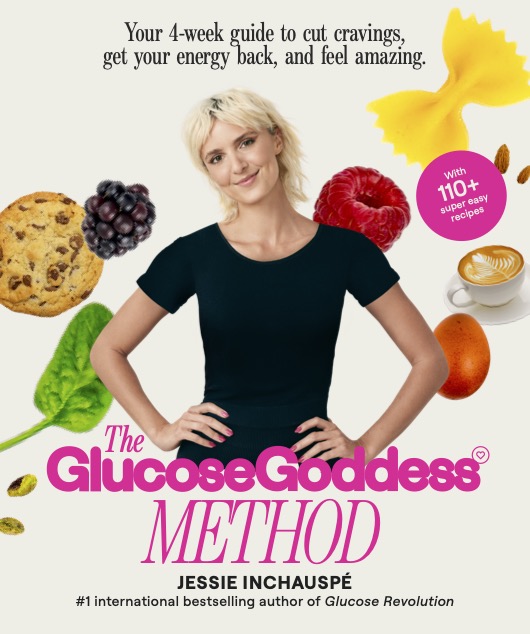

What if I told you the solution could be simpler than you think? My guest today is Jessie Inchauspé, New York Times bestselling author of The Glucose Goddess Method: The 4-Week Guide to Cutting Cravings, Getting Your Energy Back, and Feeling Amazing. In her groundbreaking books, Jessie shares how optimizing your blood sugar could be the missing link to boundless energy and reduced cravings.

Jessie is a French biochemist on a mission to translate complex science into simple, sustainable tips to take back control of your health. After earning her Master’s in biochemistry, she had an awakening that what we eat directly impacts how we feel physically and mentally. She empowers people to make lasting changes through her books and her popular Instagram account, @glucosegoddess. She teaches over 3 million people how to harness the power of steady blood sugar to live their healthiest, happiest lives.

Through her pioneering research and experiments with thousands of people, Jessie makes the case that tiny tweaks to when, how, and what we eat can steady our blood sugar. This helps cut cravings, boost energy, and elevate mood. She offers surprisingly simple and even fun hacks that let you keep having fun with your food, but in a much healthier and more “I’m in charge” kind of way.

During our conversation, Jessie shares innovative ways to minimize glucose spikes and gain control of your health. She busts a whole bunch of myths around things like whole grains and fruit and glucose monitoring, while offering insights into how timing your sweets and properly combining foods can work wonders.

If you’ve struggled with rollercoaster energy, cravings, or poor sleep, this episode is for you. Join us for a fascinating exploration of how steady blood sugar could be the key to feeling your absolute best.

You can find Jessie at: Website | Instagram

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Dr. Aviva Romm about how our hormones influence our health.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- My New Book Sparked

- My New Podcast SPARKED. To submit your “moment & question” for consideration to be on the show go to sparketype.com/submit.

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Ilulia Matei

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:00:00] The hacks that I share. First of all, they’re common sense, right? So we went over the savory breakfast. We went over the timing of the sugar, the clothes on, carbs, moving after eating. When you think about it, they’re not that groundbreaking. They’re actually common sense. But now we have science to understand why they’re so good for us, which is why I really urge everybody to try them and see how they feel. You’ll just notice cravings dissipating, energy levels improving. It’s so key. Really, really. And it’s life-changing. Seriously.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:30] So have you ever felt like your mood, your energy, your cravings just kind of seem out of control? No matter what you do, you can’t escape the feelings. Whether it’s the morning, the afternoon slump late in the evening, those intense sugar cravings that seem to hijack your willpower. For me, it often hits right around 4 p.m. and then, almost like right before I go to bed. And the cravings can feel relentless. But it’s not just the ravenous urges that are the problem, it’s the changes in physiology and psychology that underlie them, and all the other ways those changes impact our physical and mental health, both immediately, but also long term, and the way that they drive us to eat things and behave in ways that make the problem so much worse and send us into a blood sugar driven spiral of doom. So what if I told you the solution could be simpler than you think? My guest today is Jessie Inchauspé, New York Times best-selling author of The Glucose Goddess Method The Four Week Guide to Cutting Cravings, Getting Your Energy Back, and Feeling Amazing. In her groundbreaking books, Jessie shares how optimizing your blood sugar could be the missing link to boundless energy, reduced cravings, and so much better health and also state of mind. Jessie is a French biochemist on a mission to translate complex science into simple, sustainable tips to take back control of your health. After earning her master’s in biochemistry, she had this awakening that what we eat directly impacts how we feel physically and mentally, and she empowers people now to make lasting changes through her books and her popular Instagram account, Glucose Goddess, where she teaches over 3 million people how to harness the power of steady blood sugar to live their healthiest, happiest lives.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:17] And through her pioneering research and experiments with thousands of people, Jessie makes the case that tiny tweaks to when, how, and what we eat can steady our blood sugar, and this helps do everything from cut cravings to boost energy and elevate mood. And she offers surprisingly simple and even fun hacks that let you keep having fun with your food and enjoy so many of the foods that you love. And I’m raising my hand here. There are things that I want to keep eating, but in a much healthier and more I’m in charge kind of way. During our conversation, she shares innovative ways to minimize glucose spikes and gain control of your health. And she busts a whole lot of myths around things like whole grains and fruit and glucose monitoring along the way, while offering insights into how timing your sweets and properly combining foods can really work wonders. If you have struggled with roller coaster energy cravings or poor sleep, this conversation is for you. Join us for a fascinating exploration of how steady blood sugar could be the key to feeling your absolute best.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:21] So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project. So we’re having this conversation literally the morning after I just wrapped up a three-day fast. And the entire time I was tracking both blood glucose using meters and blood ketones, because I was just really curious. And I also tracked it as I broke the fast. What was happening, how quickly did my levels return? And I’ve done this before, so I kind of know how it feels. Day three is generally like really rough because there’s no easy fuel left in my body and I haven’t converted over to sort of like the efficient fat burning. So I know the feeling. But it’s always interesting to see internally what happens by tracking it. I know you’ve spent a lot of time tracking your own levels and then running bigger-scale experiments more recently with a close to 3000 people. And it’s always eye-opening because I’m so curious what your experience has been with this. You know, people have sometimes asked like, can you feel like when it’s really high or when it’s really low? I couldn’t tell you. And it’s really interesting to to literally be able to look at what’s happening in your blood and to tell you and then try and cross-correlate, like, can I actually sense this externally or am I just completely cold to what’s happening? I’m curious what your experience is around that.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:04:41] I think it really depends on the person. Um, for me, I can really tell when I’m having sort of cravings that are due to glucose spikes, or when I’m on a glucose roller coaster for the whole day craving sugar all the time. But in terms of feeling the difference in your body using glucose or ketones for fuel, I think that takes a lot of practice. You have to be like a, you know, level five, level five biohacker. But I think one thing people can relate to is how long can you go without being hungry and without eating? I think that’s a really easy one. If you can’t go five hours without food, that’s a very clear sign that your body is not metabolically flexible, that you’re only running on glucose, and if you can go, you know, five, six, seven, eight hours, then that means your body is quite good at managing your energy. I was recently doing this TV show in France, and we had to be sat on the in the studio on set for four hours while they were filming, and it was a long time. And my neighbor, after two hours, she turns to me and she’s like, are you feeling what I’m feeling? I’m like, no, what? She’s like, I feel like I’m going to pass out. Like my blood sugar’s really low. I was like, oh, you’re not metabolically flexible, girl. So I feel like the cravings and the the intense desire to eat those are pretty easy to put your finger on if you experience them. And those are a clear sign of having quite unsteady glucose levels.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:01] Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Those are some of the hints, the clues that we look for to sort of question what might be going on inside. But it’s interesting, right? Because I think most folks, if you ask them, is it typical, is it normal to sort of like have some level of craving to be like to have these hunger pangs every couple of hours or so? They would say, well, yeah, that’s completely normal. But you’re kind of saying that is probably not 100%. Definitely, but it’s probably a sign of some form of dysregulation.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:06:26] I think it is a sign. And I think, of course being hungry is normal, and wanting to eat sugar is normal because sugar gives us dopamine. But feeling controlled by urges where you know, it’s 4:00 pm and all of a sudden you’re like, I will eat anything around me that has sugar in it. That’s not normal, right? You shouldn’t have to live with these kinds of intense as soon as it interferes with your life. For example, I know people who cannot leave the house without snacks in their purse because they know they’re going to have, quote-unquote, low blood sugar, and they’re going to feel really poorly if they don’t eat every few hours. So I think we can check in with ourselves and say, okay, are my cravings feeling normal, or do I wish my cravings were less frequent and less strong? And if you’re in that camp, if you wish they were less frequent and less strong, then there’s a lot of things you can do. What do you think about this?

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:16] It sounds pretty reasonable to me, I would imagine. Also, it really depends on the person. You know, if we’re talking about somebody who’s just sort of like working throughout the day, and that’s going to be very different than if we’re talking about an elite athlete who’s probably burning 5 to 7000 calories a day with just hyper training. So I would imagine it really you really have to sort of like create that context to a completely.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:07:35] Absolutely. And depending on your lifestyle, your objectives, your goals, you know you’re going to have to eat differently. But I think where my work comes into play is that I strongly believe in the evidence supports this, that all of us benefit from steadier glucose levels. Most of us, you know, either are going towards prediabetes, type two diabetes, have some sort of symptom we’re trying to improve or get rid of, and most of us could feel better than we currently do. And so if you start from that place and if you also realize that, you know, the food landscape we live in is just quite toxic, then it makes sense to try to improve what you’re eating. And I don’t think many, many people can be, as you know, hardcore as you and do these intense fasts. I think for a lot of people, just some simple tips, some simple common sense principles can already go a long way.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:28] Yeah. And I want to dive into a bunch of those because that’s so much. Of what you’ve been sharing for a number of years now. Um, but before we get there, you just made an interesting statement, which is that quote, most of us are in some level, either like we have something going on or we’re prediabetes. What are the stats like when you look and sort of like a public health level, what are you actually seeing going on here?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:08:49] Currently, 1 billion people in the world have either prediabetes or type two diabetes. Considering this was a disease that barely existed 100 years ago. Right. So it’s a global massive trend, and the numbers are getting worse every single year. And the US is no different. I can’t remember exactly the stats in the US, but I think over half of the population either has prediabetes or type two diabetes. And then even in those who do not have a full-blown diagnosis of prediabetes or type two diabetes, studies show us that up to 80% of them can still be experiencing glucose spikes on a daily basis. That means that even if your doctor has told you that your fasting glucose levels is normal, therefore you don’t have prediabetes or diabetes, it’s still very likely that you’ll experience these spikes that can have consequences and that over time can lead to diabetes. I’m curious, Jonathan, when you were tracking your glucose levels, did you see any of these spikes? What was your data like?

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:52] Yeah, I mean, I didn’t see any spikes because there was nothing going into me that would have caused it. But I was also really curious.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:09:58] You didn’t measure your glucose levels before or after?

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:01] I did, yeah. And they returned to about the same as where they were both before and after and pretty quickly. And, you know, I was doing it largely just because I think all the various benefits of fasting, you know, once or twice a year for a slightly longer amount of time, as unpleasant as it can sometimes be, and for inflammation and things like that. But but I’m always just curious what’s going on on the inside with me. I try not to get obsessive, you know, like, and I generally don’t pay attention to these things all that much, but during these windows, I’m like, If I’m going to do this, I really want to understand it completely. You use the phrase prediabetes also, and I think a lot of people have heard type two diabetes, but maybe not as many have heard the phrase prediabetes. So what are we actually talking about there?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:10:40] And, you know, this term is quite debated. It’s like saying you’re kind of pregnant. It’s like either you’re pregnant or you’re not pregnant, right? Diabetes is a spectrum. So some folks say that we should completely eradicate the notion of prediabetes. It’s either your glucose levels are healthy or they’re too high and they’re unhealthy. But what do we actually mean? So if you experience lots of glucose spikes over years and these glucose spikes happen, if you’re giving your body too many starches and sugars to eat right over decades, every time you experience a glucose spike, your body knows that these spikes are not good for you. And these spikes lead to inflammation aging. They mess up your hunger hormones. They lead to cravings. So when you experience a glucose spike, your body does its best to try to bring those levels back down. And the way it does it is by sending out a hormone called insulin from your pancreas. And Insulin’s job is to grab the excess glucose and store it away in your liver and your muscles and in your fat cells. And insulin is fantastic. And she helps us get those levels down. But the problem is, Jonathan, over time, as this happens every day for a decade or two, the amount of insulin in your body starts getting quite high.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:11:54] And then you experience what’s called insulin resistance. And it’s a little bit like, you know, I’m drinking a coffee right now, but the first time I had a coffee, I think I was 16 or something, it kept me up for two days, you know, I was like, whoa, this stuff is strong. And then six months in, I’m having three coffees a day and it doesn’t really do much anymore to me. While insulin is quite similar, over time your body becomes less responsive to insulin. It becomes resistant to insulin, just like you can become resistant to caffeine. And this insulin resistance means that your body can no longer store excess glucose effectively in these storage units. So your glucose levels start rising. And that’s what’s called insulin resistance. And it’s a spectrum. And at some point when your glucose levels rise to over 100mg per deciliter, that’s called prediabetes. And then when it’s over one 26mg per deciliter, that’s called type two diabetes. But really the underlying issue is the insulin resistance. Haven’t gotten to a point that is too much for your body to handle. You see what I mean? So it all happens really gradually. And insulin rises for years before you might get a prediabetes diagnosis.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:05] Yeah, it’s the type of thing where it’s, um, it’s generally not something that unfolds in a year or two. It’s probably something that’s been building over a long period of time, but it doesn’t really get picked up or acknowledged until you sort of like trigger a certain number and maybe an annual physical when you get your labs or something like that, which.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:13:23] Is wild, right? Because let’s say you go to your doctor and your glucose is 99mg per deciliter, your doctor might not say anything because it’s underneath. This arbitrary cut off of 100. And then as soon as you get to 100, then you have prediabetes. Well, actually we should be looking at glucose levels. Anything above 85 should already be cause for trying to adapt your habits and making sure it doesn’t get any higher than that. So but that’s the medical system for you, right? It’s like diagnosis medication and um, not so much support or information for people who are trying to prevent the disease in the first place, or for people who are trying to put it into remission once they have it. Because often when you have this diagnosis, you’re given medication to, quote-unquote, manage it, but you’re not given super good guidance about how to reverse this high fasting glucose value.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:14] Is it widely known and accepted within the medical community that this actually is something that is reversible and not just treatable?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:14:21] I think there’s lots of factors going into this. Um, I think most doctors do realize, yes, of course, that you can put diabetes into remission, although a lot of doctors who see my readers reversing it are quite shocked. But then I think for a lot of people, if you tell them, okay, you have two options, you can take this pill or you have to change what you’re eating. I think a lot of people would rather just take the pill, right. And then the medical system is incentivized to give you that prescription because that makes money for the pharma company, etc.. And behavior change is difficult. But if you look at, for example, you know, the American Diabetes Association, etc., like they do endorse, for example, low-carb diets to help you manage or put diabetes into remission. But the the common narrative is not, oh, here, do these hacks and you’ll be able to get that fasting level down, which is what I’m trying to change. I would love to see, for example, when somebody has a pre-diabetes diagnosis, that the first line of defense is to say, okay, use these glucose hacks for three months, see if you can get it down. And then we reassess. That would be great. But most people are just told eat better, exercise more, or take this pill. And that’s just super vague, not very helpful advice that most of us don’t know what to do with.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:33] Let’s say somebody listening to this now and they’ve recently gotten a diagnosis of pre-diabetes, and they’ve been prescribed whatever the medication is and they’re taking it and it seems they’ve had they wait three months, they get their blood tested and it seems to be better. What is the downside of treating this through some sort of, you know, like pharmaceutical intervention versus lifestyle change?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:15:53] I think the downside is that you’re going to need more and more medication as time goes on. If you don’t change the underlying cause of the condition, which is eating, you know, too many refined carbs, too many sugars, too many processed foods, then over time, you’re going to need more and more of the medication, and it’s not actually going to cure you, right? It’s going to help you manage and reduce the symptoms. It will often lead to weight gain, because one of the things that these medications do is to force open the cells that have become insulin resistant to accept more glucose. And so 30 years down the line, you might start getting more and more hardcore medication because the underlying issue has not been fixed. And I think it’s such an interesting problem because you also hear people who have got a diagnosis who believe it’s genetic. Maybe their doctor was like, oh, it’s just a family thing. Or they heard that diabetes was genetic. It’s not a genetic disease, right. But when you think about inheriting things from your parents, for example, you don’t inherit just their genes. You also inherit their lifestyle, their food habits, their socioeconomic status. So we have to differentiate all those things. And it can be quite difficult to to understand what’s really going on. But what I’ve seen in my community is that if you do apply these hacks and you are interested in testing them out, they will help. And if you are on medication, don’t stop the medication. But do these hacks in addition to it and then go back to see your doctor. And your doctor might take you off the medication.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:24] Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And what you just shared about the medication, one of the mechanisms of action is to effectively sort of open the storage areas so that more of that glucose can be stored. Well, the prime storage area is generally fat cells in your body. So that. Exactly. Yeah. Which and you know leads also like and then the side effect of just increasing the volume of fat cells is systemic inflammation. So it’s sort of like it sounds like it kind of solves one problem, but probably seeds a whole bunch of others.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:17:53] It does. Yeah, it’s a little bit like and the comparison isn’t perfect. But imagine somebody going through alcohol withdrawal. One of the ways you can help them is by giving them more alcohol to drink, right. That’s going to remove the withdrawal symptoms and mask the issue. But that’s not actually solving the underlying problem of this person is drinking too much alcohol. And we need to help them not drink so much. So it looks good from the outside. But when you actually understand how it functions, you realize this is not helping this person become a healthier version of themselves. This is not helping them have more freedom and agency over their lives. It’s kind of just making it more and more difficult to. Change. What’s going on?

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:35] So you described this effect where somebody has, I guess, like too many refined carbohydrates or sugars and their system is equipped to handle, then their insulin can sort of like in an intelligent way, balance out, and then they get a spike in the level of glucose, because basically it just kind of sits in their blood and jumps up. I guess one of the questions also is what is the harm here? You know, and and is it is saying that your glucose is spiking. Where do you cross the line between a normal spike or like a, like a typical spike and an atypical or harmful spike? Because I would imagine there are certain scenarios where it’s it’s not a big deal if your glucose is spiking or am I wrong there? Is it always a big deal?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:19:18] No, no. You’re correct. So in some cases you might spike from exercise. In that case, it’s not a bad spike. In some cases, your glucose might stay steady because you’ve added, you know, a 2 pounds of butter to something that’s also not a good way to steady your glucose levels. So it’s quite nuanced. But I’ll tell you that the sort of scientific definition and then how we can apply it to our lives. So scientifically, currently a glucose spike is defined as an increase of more than 30mg per deciliter after eating. And the way this we arrived at this number is by looking at healthy individuals who eat a balanced diet, a balanced meal, and noticing that their glucose does not spike by over 30mg per deciliter. So we’re like, okay, if you’re eating in a balanced way with proteins, fats, fiber, then and some carbs, of course, then your glucose should stay sort of in that range. Now, the thing is, I don’t love obsessing over this number and you’ll see it in my work. I, I talk about the increase, but I also just show people the comparison between two different spikes. And what I want people to really get at is to understand which version of this meal or of this snack is leading to a relatively smaller spike, because all of us could benefit from just generally reducing our spikes, whatever the actual number is.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:20:41] Generally, wherever we start from, whether we have type two diabetes and our spikes are super, super high, or whether we’re super healthy like you are, reducing your glucose spikes is always going to be beneficial to a point, right? So you don’t want to obsess over keeping a very flat glucose curve, because that could be done with really unhealthy habits like adding lots of alcohol to a meal, adding lots of unhealthy fats to a meal. So I use the spikes as sort of visual aids to explain these scientific discoveries to people. But I tend not to focus too, too much on the absolute value, and I tend to not recommend that everybody wears a glucose monitor, because I think you can get a lot of benefit from just seeing how you feel and noticing that generally your glucose levels is steadier. Generally, your cravings are dissipating, your energy levels are better. So I like to be a bit less data biohacker and a bit more like just notice how you feel and if things are improving. Does that make sense?

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:42] Yeah, no, it definitely does. And I guess a year or two ago I spent a month wearing a continuous glucose monitor. And and I learned really quickly how obsessive that can get. And, you know, to a certain extent, you know, it’s interesting to know, but, um, it can trigger all sorts of other obsessive tendencies. And I found it really interesting, and I hadn’t really been super compelled to go back to that level. Um, and I guess the question is, is the danger come from regularly spiking your glucose? And is there any danger in occasionally because I’m thinking, you know, okay, so I try and eat healthy most of the day, but every once in a while there’s an like, I’m at a dinner with friends and there’s this awesome dessert that’s being served. And like, I know, like, that’s going to affect my blood sugar in a really major way. Yeah, I would imagine the occasional spike like that probably isn’t what we’re talking about here, right?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:22:31] Correct. Yeah. So we’re not talking about always avoiding glucose spikes and running away from sugar. Actually, I don’t think sugar carbs should be off-limits at all. And we don’t have a specific number of like, oh, you have two spikes a day that are fine. And if you go to three spikes and everything is going to be messed up, that’s just not how biology works. Just generally, if you can, for example, compare two weeks of your glucose data and say, oh, you know, week one, I was quite spiky. It was a high variability. And then week two, it was steadier. That’s the kind of objective I want people to focus on, just the overall trends, not focusing too much on a single meal, a single dessert, a single day, just seeing whether over time they’ve been able to implement habits that are keeping them steadier. You see, I think it’s more a, um, a long time frame habit change behavior change principles that stay with you for a long time and that you do whenever you can do them, versus being super stressed out about having dessert. I eat dessert all the time. I love chocolate, I love pasta. The point is not. To go keto and never eat carbs ever again. That’s a fad and it’s not going to work, and you’re not going to be able to do it forever. But when you do eat the nice dessert, for example, remembering to move your body afterwards for ten minutes instead of staying sat down at the table for an hour and a half, or, you know, having a little vinegar drink before it can be helpful. So it’s enjoying the sugar that you like and the carbs that you like, while using these little hacks to reduce their impact on your glucose levels and on your health.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:04] Yeah, that makes so much sense to me and it makes it so much more livable. You know, we’re not talking about having to live the life of a nutritional ascetic for the rest of your life. It’s like, no, God, enjoy the things you want to enjoy. You know, like with moderation. And also you have like so many great strategies to say, like there are little things that we can do that will make a big difference. And I want to drop into a bunch of those. But there’s one more thing that I actually just want to deepen into before we get there. And that is the impact of these regular spikes you’ve mentioned. You sort of teased out its impact on physical health. Is there also an impact on mental health that’s been identified? Yes.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:24:38] And this is actually the reason I got into this topic in the first place. So I started noticing I was having a lot of mental health issues. And when I was younger and I started noticing after putting on a glucose monitor for the first time, that the days during which my glucose levels were steadier, my mental health was better, and the days during which I had lots of spikes and drops, my mental health was worse. So for me, it was an incredible eye-opening discovery because for years I had no clue what to do to improve my mental health. And then I started realizing, wait a minute, maybe my food is impacting how I feel. And that was revolutionary. And then I looked into the research and listen, we have some big studies showing, for example, that if you have anxiety or depression, putting you on a diet that is going to minimize processed foods, glucose spikes, glycemic load, your symptoms will get better. But we don’t have very specific sort of mental health condition by mental health condition, connection between the spike and that medical condition. We just know that food impacts the brain, food impacts inflammation in the brain, insulin resistance in the brain, glycation in the brain.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:25:47] Food also impacts your gut and in your gut. So many molecules are produced that impact your moon, your mood, and your brain, right? The gut-brain axis. And I think we’ve all been able to experience just not feeling great after eating a lot of sugar. You just don’t feel so good. You feel a little bit gross. You feel a little bit, um, sad and not really comfortable. Even just that shows you the connection between food and mental health. And for me, it was it was a complete 180. It allowed me to understand that if I kept my glucose level steady, my mental health would be better. And that’s what I did. And then it helped my it helped me build back my health. So getting my glucose levels under control was sort of the the foundation in my new health journey. And then on top of that, I was able to add, you know, therapy, eMDR, emotional processing, etc. but getting that food part under control was such an important first step.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:44] That makes so much sense. And yet in I think in the world of mental health, it’s still a fairly new and some sometimes contrarian concept. We had Chris Palmer on last year from Harvard, who’s like, done all this really fascinating work on nutrition and mental health. And the outcomes that he was seeing, even just on a patient level, were stunning. And I guess now he’s really trying to really broaden this out, and it really supports what you’re talking about here. What about the relationship between glucose and sleep? Like, is there a bit of a bidirectional thing that’s kind of happening here? Like one influences the other which influences the other.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:27:16] Exactly. Big glucose spikes before you sleep. So for example, a big spike after your dinner is going to impact the quality and the depth of your sleep. So if you go to bed with a big glucose spike happening, you’re not going to have as much deep restorative sleep. And in the morning you’re going to wake up more tired. And now the problem is when you wake up tired, then for that day, your body’s not going to be as good at keeping your glucose levels steady. So anything you eat will create a bigger spike than usual because your body is tired. And so this becomes very quickly a vicious cycle where you woke up tired because you didn’t sleep well. So your whole day is going to be bigger glucose spikes. So you, you go to bed with a big glucose spike happening and you wake up tired again. And it’s not just the sleep piece that is so interesting. It’s also the fact that with glucose spikes, your mitochondria become stressed and overwhelmed and your mitochondria are in charge of making energy for your body. So not only are you sleeping poorly, but during the day your mitochondria are not functioning properly, so you are even more fatigued and you end up in this wild universe of being exhausted, waking up exhausted, not getting the rest, and the restoration you need at night. The cool thing is, you can actually do a lot about this. So if you just change, for example, your. Breakfast from a sweet one to a savory one. That is the first step to getting your sleep under control. But it’s quite counterintuitive, because you wouldn’t think that how you sleep at night is impacted by what you had for breakfast that day. But it is.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:47] And that’s amazing. Subtle tweaks can make such a big difference. And it’s like, I would imagine once that cycle starts, you know, and the longer you’re in that cycle, the harder it is to sort of like short circuit that. Which makes me curious also about when I think about sleep and glucose, I also start to think about exercise. Yeah. And how that fits into it. And I wonder, is there this sort of feedback mechanism there to where if you exercise. Well, actually, counterintuitively, I was going to say if you exercise immediately, I would think, well, that would probably lower glucose because you’re using that for fuel in your body. But you said something earlier in the conversation, which is that sometimes exercise actually causes a co-spike. So take me there a little bit more.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:29:25] And that’s one of the limitations of wearing a glucose monitor, because you might see these patterns and draw wrong conclusions. So if you exercise vigorously, especially on an empty stomach, your body is actually going to pump out glucose into your bloodstream to feed your working muscles. And that can show on a glucose monitor as a spike. But this is not a bad spike because when you’re exercising, your muscles don’t actually need insulin to uptake glucose. So you’re just using up stored glucose. It’s really healthy. It’s really good. And exercise at any time is fantastic for you. I mean, whatever kind of exercise you do, that’s great. However, if you want to really optimize for your glucose levels, one of my hacks is moving your body using your muscles after eating for ten minutes. Because as you do this, your muscles are going to use some of the glucose from the meal you just ate for energy. Instead of letting that glucose just sit around in your bloodstream and create a big spike. And then also an important piece of this is to build muscle mass, because your muscles are such an important storage unit for extra glucose that your body uses when there’s a spike to store this extra glucose away. So building muscle, having a lot of muscle mass. And you do this by lifting weights, eating protein, I mean pretty pretty basic. And then after eating, if you can move just a little bit and you don’t have to go to the gym, you don’t have to run a marathon. Even just tidying your kitchen or your apartment, or picking up your kid for five minutes, or walking the dog that already can have a really wonderful impact on your post-meal glucose levels. And I.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:05] Love that. It doesn’t take a lot. We’re not talking about, you know, doing ten minutes of push-ups and jumping jacks. You know, it seems like more of just a moderate level of movement, actually would do the trick for most people. Is what you’re saying totally.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:31:17] What’s your exercise sort of a habits regimen routine. What do you do?

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:22] Yeah, I mean, for me, I’m just incredibly blessed to live. You know, where I walk out my front door and in seven minutes, I’m hiking on some of the most beautiful trails in the world and some of the biggest mountains in the country. So I hike on a regular basis. It’s my happy place. And then a couple times a week I’ll try and do resistance training also. But um, but I have noticed that I just feel a little bit better if we do like, you know, just an after-dinner walk around the block or something like that. I think that makes sense. But here’s the other thing. That’s that was sort of like occurring to me as you’re describing this. I do remember back during that one month where I was wearing a continuous glucose monitor, you know, I would go for a hike for an hour and a half, not too strenuous, you know, but just something super comfortable for me. I remember coming back from that one day and just sitting in my living room talking to my wife and a friend, and I started getting all of these beeps, these alerts from the monitor because glucose was crashing. It was going really low. It was down to, I think 40 or 50. At one point. I felt completely fine, though, you know, and the monitor is saying this is dangerously low, but I’m sitting there saying, I feel completely fine, like I’m good. What’s your sense of what was going on there?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:32:32] The monitors are not accurate. They’re just not very good at picking up. They’re meant for people with diabetes who have massive swings and who do go really low and who do go really high. So in a person that has normal, healthy glucose levels, it’s not going to read very accurately. So there’s nothing to worry about. People will also see at night if they’re wearing a glucose monitor, they’ll see that their levels are going really low at night into, you know, the red zone on the app. Again, nothing to worry about with the glucose monitor. The interesting thing is to look at the variation. You know, the spikes, the drops, the overall shape. But I wouldn’t really trust the absolute number. To give you a counter-example, I was wearing a glucose monitor not too long ago, and it was telling me that my baseline glucose was 110. So it’s telling me I had prediabetes and I was like, what? And so I freaked out. And then I went to the doctor and did a proper blood test. My fasting glucose was like 87. So it just goes to show that you cannot trust.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:33:34] The absolute values on these devices. And that’s another one of their limitations. And that’s another reason, I think it’s important for people who wear one to have lots of education. And my first book is a really good place to start. And this is not a plug. It’s just simply I’m just looking out for people who went on for the first time and become super overwhelmed with all of the data and all of the patterns. I mean, listen, even I sometimes don’t understand at all what’s going on. I’m like, huh, that was a weird, weird spike spiky thing. I have no clue where that came from. And that’s pretty normal. Which is why, again, I think what you said is so key, right? You said I felt absolutely fine. And that’s the important piece. If you felt fine, then trust yourself. Trust your body. If you were really having a hypo, you would not feel fine. You would be on the ground, you would not feel okay at all, and somebody would probably call an ambulance. So don’t worry too much about the lows.

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:30] Yeah, and I wasn’t I just I found it more curious than anything else. I was like, huh, like what’s going on here? And then actually started researching and like validated what you’re saying here, that those monitors, they’re not actually measuring your blood glucose, they’re measuring the glucose in your interstitial fluids and sort of like saying, okay, so we can make an approximation if it’s if it’s if it’s that, then we’re going to guess that this is what your blood actually has. But it’s not always the correlation that you know it needs to be. And that was really interesting to see.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:34:59] It’s an algorithm that is taking electrical signal and trying to convert it into a raw number of glucose molecules. But it’s imperfect. It’s it’s inaccurate. It’s great for people with diabetes who really need to see these big swings and, and address them with medication. But for somebody without diabetes, the number is not that helpful. I always tell people, ignore the number, look at the variation. That’s all that matters.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:23] Yeah, that makes so much sense. As you mentioned, your first book, Glucose Revolution. It’s a really nice deep dive sort of overview of like, let’s really just explore this and what’s about and let’s talk about some of the hype and some of the not hype. A lot of your work has been focused on both a combination of understanding strategies and hacks to help control the spikes, but also there’s like a healthy dose of myth-busting in your work as well. What I found, and one of the things I thought was really interesting, is what are some of the things that we tend to do or eat that we think are completely healthy and would like not affect us at all, but make these huge spikes? What are some of the sort of like the myths or misunderstandings that you think we have that you’ve seen sort of most common.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:36:04] You know, fruit juices, cereal, muesli, granola or foods that are made from fruit. For example, you might find a cereal bar or a cookie that says, you know, 100% natural sugar, 100% made from fruit. And I think often we have the misconception that, oh, if it comes from a piece of fruit, then it’s good for us. So, for example, somebody might think a glass of orange juice is a great way to get my fruit for the day in. Or, oh, you know, this cookie or this cake uses dates to sweeten instead of real bad table sugar. And actually, what I’m really passionate about explaining to people is that the source of the sugar does not matter to your body at all. So whether the sugar came from an orange and is now in a glass of orange juice, or whether the sugar came from a beetroot and is now in a can of coke, your body does not process them differently. What your body cares about is the matrix that the sugar comes in. So if the sugar is in, let’s say, a piece of whole fruit that contains fiber and water and is eaten slowly because eating an orange takes some time, then your body is going to process it better and the fiber in there is going to slow down the spike. But as soon as you take the sugar out of something and you just put it in some water, in the case of a juice, or in the case of a Coca-cola, then your body is getting this big, big glucose spike, this big rush of sugar all in one go. So I think that’s one of the most common misconceptions, Jonathan, that if sugar comes from a fruit, then it’s good and it’s natural. And if sugar comes from table sugar then it’s bad for you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:37:51] You also mentioned breakfast foods, and I think a lot of people look at, you know, well, let me have something that is whole grain because that’s going to be the healthier thing. Deconstruct that a little bit.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:38:01] Well, often when you see, for example, a slice of bread that is whole grain, so it’s brown or pasta that is brown instead of white, you’ll think, oh, the whole grain version is so much better for me. But actually it’s not really often the whole grain version is very similar for your body than the regular white version. It just looks healthier because the color is darker, and that color is created by the food companies to make you believe that it’s better for you, and they do leave a little bit more fiber in there, but the difference is very minimal. And I have a lot of these comparisons on my Instagram account. So for example, white bread versus brown bread or even white rice versus brown rice actually have a similar impact on the body. So when it comes to choosing your carbs, don’t worry so much on the side of white versus whole grain. Think a bit more about what I call putting clothing on your carbs, which means to never eat your carbs naked. So if you have bread, add some avocado to it and you know some a slice of cheese, add some peanut butter. Because when you do that, you actually are adding these extra molecules of fat and protein and fiber, and those actually have a big impact on the glucose spike of that bread way. Much, much bigger impact than just the color of the brain or regular versus whole grain. And such a big misconception. People think that if it’s whole grain, then it’s all of a sudden this health food, but it really isn’t. It’s just another marketing trick.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:33] And I don’t want that strategy that you just shared to get lost in the conversation to, which is this notion of if you combine foods in interesting ways, that you can have this thing that you really want, but it completely, it really radically alters either whether you’re going to have a spike or the the intensity and the duration of the spike. So you just mentioned if you can integrate a fat or a protein or a source of fiber, or maybe all three, if it makes sense that this can be one strategy that you can kind of apply across the board.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:40:04] Exactly. It’s a great strategy. So putting clothing on your carbs and it works for if you want to eat a cookie, we’ll have five almonds with the cookie. If you want to eat a slice of cake, have a Greek yogurt with it. If you want to eat bread, add something to that bread. If you want to have pasta, make sure you’re also adding some protein and some veggies to that pasta. It’s one of, you know, my most popular hacks because it doesn’t actually ask you to eat less. It asks you to be smart about combining and how you’re eating your carbs and with what. And when you do that, you create less of a spike in your body, therefore less likelihood of starting kicking off a craving roller coaster for the rest of the day, which is something that so many of us are so familiar with. You know, you have one sweet or starchy thing, and then you want more and more and more every two hours until midnight.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:50] So I actually tested this when back when I was wearing that glucose monitor, I was following you, and I’m like, I want to basically writing down all the different strategies and reading the books. And so I had a banana and I watched like a really big spike happen just like a, like a big spike. And then the next day I had I wanted a banana again, but I started with some almond butter instead, and it definitely lowered the spike a bit, which I thought was really interesting. But then what I saw happen was, I don’t know what you call this, but it was like a rebound spike, like it lowered it and it started to come down faster. But then it was like, you know, there was like a double hump in the curve. It kind of jumped back up a little bit before it went back down. What’s your take on what’s happening there?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:41:34] There’s so many reasons that could happen, but a few off the top of my head. Sometimes when you eat something that’s quite fatty, the digestion happens in two stages. So you’ll see your first wave of glucose arriving and then the second one. Or sometimes it’s because when insulin gets released in the body, there’s sort of the immediate fast one. And then the longer, slower-acting one, if you will. And so you might see a big spike, a big drop, and then a second spike and another drop. And it just has to do with how your body is releasing insulin. It could also be something as simple as maybe you were walking at some point and then you stopped walking. I mean, there’s so many variables. Maybe you ate the banana and the almond butter. What’s important is that your body was able to get your glucose levels back down to baseline. That means you’re healthy metabolically. What would be quite concerning is if your glucose spiked really high from the banana and then didn’t come down at all for like 12 hours, that would indicate that there’s insulin resistance going on.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:32] Got it. No, that makes a lot of sense. And as you’re describing that also now I’m thinking, did I sleep poorly the night before. They could have been so many other things. You know now that you shared how like sleep informs it.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:42:40] There’s so many variables, what’s important here and what you discovered is that banana on its own created a bigger spike than the banana and almond butter. And that’s really the key I want to focus people on is that if you use one of the hacks, the spike will always be smaller. It might look a little weird. It might do something. Your spike versus my spike might look quite different, but by both using one of the hacks, we are both reducing the height of the spike. And that’s the key here.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:06] Yeah. And I saw that in I did a second experiment also where one day I just had a plain piece of bread and I saw like a decent sized spike. And then the next day I had it with avocado and a little bit of olive oil drizzled on top of it, and it definitely made a difference. So food combining I think is a really interesting strategy, but it seems like part of what we’re talking about here is also timing. Yeah. Tell me a little bit more about sort of like the timing aspect of it.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:43:30] I think the best way to explain how. Timing impacts things is if you look at something sweet that you want to eat. So let’s say you’re, you know, you love pop tarts. Well, the timing, the moment you will eat that during the day will have a massive impact on how it’s going to affect your glucose levels. So if you have that pop tart first thing in the morning on an empty stomach, that’s going to create a very big glucose spike. If you keep that pop tart for dessert after lunch or after dinner, all of a sudden the spike will be so much smaller because there’s other stuff in your stomach. And this is cool because it allows us to get the pleasure hormone from eating sweet foods with less impact on our glucose levels. And that’s another one of my hacks, which is never start your day with something sweet. If you want to eat something sweet, always have it as dessert after a meal. Never first thing in the morning, never as a snack between meals because you really want to avoid creating a big, big spike from sugar. You want to time it to be after a meal for dessert to minimize the impact it has on your health. That’s a very key piece of information that I really want people to remember.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:43] So as you’re describing that, like one thing that popped into my head is there would be times when I would actually start my day with a protein bar, but the experience of it was to be sweet, and it was either sweetened with stevia or xylitol. And one of those things when we’re talking about artificial sweeteners, where it goes into my mouth and I’m like, oh, this is sweet. This tastes like candy to me. This is awesome is the presence of either the sensation or the experience of sweetness or the presence of artificial sweeteners. Does that come into this conversation?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:45:14] Sometimes artificial sweeteners can create a small glucose spike. Sometimes they can create an insulin release because your body thinks there’s sugar coming down when there’s none. And there’s been such a big conversation about artificial sweeteners. And while they’re not particularly good for our health, right. And things like aspartame, maltitol should really you should really try to avoid them. Other things like stevia, monk fruit, allulose actually seem pretty fine for you. I want to make sure people understand that while these may have consequences on your microbiome, on your craving center in your brain, on your insulin. The impact of real sugar is so much worse. So it is always better to drink a Diet Coke than a real regular Coke with 25g of sugar in it. Always. I get a lot of, um, criticism for this, but I don’t understand how somebody looking at the evidence can think, oh, I should switch from Diet Coke to real Coke because it’s more natural and it’s going to be better. For me. It’s not the impact of sugar on your brain, on your microbiome, on your craving center, on your insulin are so much worse than the impact that sweeteners may have on those aspects of your body.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:30] Yeah, that makes sense. It’s interesting also that you said that, um, your body can almost have like insulin response just because if you taste something sweet, it’s like this. The flavor experience signals to your body. There’s something sweet coming in. The natural way that sweetness arrives is with like simple carbohydrates or sugar. So I need to actually kick in the insulin response. Maybe it’s a lot less, but it’s fascinating the way our body sort of responds in that way.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:46:56] Fascinating. It’s so so so so interesting. Yeah. And we haven’t even scratched the surface. You know, in 50 years we’re going to look back and think, wow, we did not know anything about how the body functioned. And that’s great. But today the hacks that I share, first of all, they’re common sense, right? So we went over the savory breakfast. We went over the timing of the sugar, the clothes on, carbs moving after eating. When you think about it, they’re not that groundbreaking. They’re actually common sense. But now we have science to understand why they’re so good for us, which is why I really urge everybody to try them and see how they feel. And even if you’re not wearing a glucose monitor, you’ll just notice cravings dissipating, energy levels improving. It’s it’s so key. Really, really. And it’s life-changing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:42] Seriously, I agree, I think, um, cravings and energy levels are just really good signals that we can all key in on also. In your second book, The Glucose Goddess Method, you sort of built on a lot of the work that you’ve been doing and said, okay, so let me lay this out in more of like a systematic, programmatic way for people. Like what happens if we if we allocate a month or so just to try and sort of like reorient our system, what would that look like? And you have a sort of a four-week program and a whole bunch of like, interesting recipes and stuff like that. Walk me through the idea behind, like, why you wanted to create this.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:48:17] Well, because in my first book, I had ten hacks that all were very useful. But my readers, some of my readers, wanted a clearer step-by-step guide. So a lot of people after my first book, they messaged me and they said, Jesse, can you move in with me and help me actually do the hacks? And so I thought, okay, well, I can’t move in with anybody, but I’m going to create a four week method to help those who need it to help them with a step-by-step, week by week hack by hack guide with loads of recipes to actually do the hacks. So if you’re somebody who thinks that they need more structure, more hand-holding, a very clear day-by-day guide, this is this is the book for you. And so in this second book, I focused on the four most important hacks from the first book. And I envisioned this method as a as an on ramp to the freeway. You know, once you finish this four-week method, your glucose levels will be steadier. You’ll feel so much better. And then your whole life is ahead of you with with better health and and better health as you age. Because most of us are. Health deteriorates as we age, and I firmly believe that we can change that and actually improve our physical and mental health as we get older.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:30] I love that you provide recipes also, because I think a lot of folks are kind of like, does this mean I’m just going to have to strip it down and like eat really, really boring ways? No. Gone with the food combining with the hacks and stuff like this. And it’s like you lay out a whole bunch of things and say, no, this actually sounds pretty delicious when like you think about it and you don’t have to just cut out all of the pleasure side of eating.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:49:51] Exactly. And doing the method. You don’t have to cut out foods. You don’t have to cut out sugar. You can eat whatever you want. Just do these four hacks, and the rest of the time, live your life like you normally would, and you will notice that naturally, cravings dissipate. And you you don’t really want that chocolate bar anymore. It’s amazing to see how your experience of your day changes as you steady your glucose levels. It’s really something to to test out because it’s so wonderful.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:15] Yeah, what would be I know you have sort of anytime main dishes. You have desserts if you know off the top of your head or if you have a sense, what do you feel is maybe like the most popular dessert that you recommended? Like, what are you hearing tons of feedback on?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:50:31] Well, there’s a dessert in there. It’s called the salted Nut Chocolate brittle. And I actually made some last night because I would say it’s my favorite dessert from the book. It’s so, so good. But all these recipes are either a family recipes that have been passed on to me by my grandparents, my mom, my sister, or recipes that I developed over the years to keep my glucose levels steady. So that’s a dessert one. I would say the breakfast one that is super popular. There’s a couple. One is the two-egg omelet with feta and tomatoes, which I make three times a week. Another one is the savory jam on toast. So I wanted to make a sort of a parallel with the with the jam on toast breakfast that a lot of people have, and make a savory version of it. So you roast peppers, you use feta, you make this really cool little savory jam and have it on a piece of sourdough bread. You can add some tuna or something like that anytime. Main dish is the one that comes to mind. Is my favorite San Francisco salad, it’s called. So I lived in SF for five years, and I became obsessed with this Greek restaurant that had this really good orange and chicken salad. So a lot of these recipes are just from my life. But, um, yeah, these ones are quite popular.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:40] Yeah. I mean, I’m sitting here like, I’m like, as soon as we end, I’m like, I need to go flip open to those pages because lunch is coming up. So.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:51:46] Yes, exactly. Try the San Francisco salad. It’s so good. Yeah, that sounds amazing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:51] You also just mentioned that in one of them sourdough bread. Is there a meaningful difference between sourdough versus other types of bread?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:51:57] There is because during the fermentation process, a lot of the carbs get digested during the sourdough fermentation process. And so it’s it’s actually creating a much smaller spike on your glucose levels. So that’s one of the cases. Sourdough and really dark rye bread are better for you than the whole grain or the white counterparts. So if you can find those, then it is actually quite worth it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:19] That’s interesting because I’ve also talked to folks who are who have some level of gluten intolerance, and they’re they’ve shared that sourdough is often much easier on their system. So it’s interesting to hear that it also may be easier on their system from a glucose standpoint. Exactly.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:52:32] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:32] So zooming the lens out here, you have been, as you mentioned, a couple of times. Also, you didn’t start out with this focus. I mean, you went you have a master’s in biochemistry. And but then you kind of went into you were actually the tech world for a little while in San Francisco and then really start to focus back in. On this, and you’ve devoted effectively the last 4 or 5 years to just going deep in this and yeah, almost being like a glucose whisperer publicly, like, can we make this fun and interesting but actually share really good information? But I know that you recently teased on Instagram you’ve got a really big announcement. Something big to share. Can you share that with me knowing that that this will actually air? Well, after that announcement comes out.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:53:16] Absolutely. So I’m launching my very first product. It’s a capsule, a supplement you take before eating, and it cuts the glucose spike of carbs by up to 40%, four 0%. It’s all the latest ingredient science 100% plants, plants that have been around for a very long time, but that recent clinical trials have shown to grab 40% of the carbs from a meal you just ate and not let it go through to your bloodstream. And I actually have one here I can show you. It’s called Anti-spike formula. And I created this because, as you can imagine, over the years, so many of my readers have asked me for a fiber supplement, a vinegar supplement. Is there something I can take when I cannot do the hacks? Maybe I’m traveling. Maybe my father has diabetes and doesn’t want to change his diet at all. Is there something we can add to our little tool belt of glucose hacks to help us? And several years in the making, and I’m very, very proud of it. And I hope people will, you know, carry this in their purse. So when there’s a surprise birthday party and they want to reduce the spike, they just take a little capsule. And it helps.

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:27] I mean, that sounds amazing. I get the immediate question that pops into my head is how are the mechanisms in the nutrients in the supplement different than what would be inside of a pharmaceutical capsule that you would use to try and sort of like counter glucose spikes in a way that’s healthier for you?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:54:45] Well, this is quite different because this is not a it’s not a pharmaceutical drug, it’s plants, but it’s specific molecules that are extracted from plants. So the plants we have in here are white mulberry leaf, lemon extract, cinnamon and antioxidants from green vegetables. And the mechanism is as follows. So in the white mulberry leaf there’s a molecule called DNA. And DNA interacts with the enzymes in your stomach and sort of prevents them from breaking down 40% of the carbs from that meal. And then the undigested carbs make their way to your microbiome, where your microbiome very happily feeds on them, and then increases a bunch of amazing downstream molecules. For example, GLP one, which is the satiety hormone that ozempic, etc. acts on. So, for example, if you compare this to Ozempic, which is actually a quite good comparison, Ozempic acts in a much more hardcore way. So Ozempic will trick your brain into thinking there is more GLP one in your body than there actually is, and it’s quite a hardcore drug. Anti-spike formula, on the other hand, will actually naturally increase GLP one over the course of six weeks by 15% using the natural physiological pathways of food versus a drug that is coming in and just tricking your system into thinking something is happening when it’s not.

Jonathan Fields: [00:56:10] Interesting. I’m also surprised I would have guessed that one of the ingredients that you would have mentioned would have been berberine, because there have been so much conversation around it, but it’s not a part of it. So I’m curious about that.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:56:21] Berberine is interesting, but I don’t think the science is that strong. You also need to be taking it for a very long time in order for it to have effect on your glucose levels. While anti-spike acts immediately on the glucose spike of your meal. Berberine. It may seem that actually it also tends to increase insulin levels, which you don’t want. So I’m not super hot on berberine. I think it’s cool, but I think what I’ve created and the clinical trials that support it are much stronger, and I just have more confidence in them than I would have in berberine. But as you can imagine, I looked all over the market to and all over the studies to try to identify the best-in-class ingredients to put in here, and berberine just didn’t make the cut. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:57:05] Which is okay. I think berberine will be okay with that. Um, when you look at the work that you’ve been doing and you look at the books, you look at this supplements that you’re bringing to market now, ten years ago, would you have imagined you’d be doing this?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:57:19] God, no. Ten years ago I was 21. What was I even doing when I was 21? I think I was even five years ago. Yeah. No, honestly, it’s kind of a whirlwind. It’s really wild. I’m just writing it and enjoying it and realizing that it’s so wonderful to feel like I have a purpose. You know? That’s really cool. I wake up every morning, I’m like, okay, my job is to make sure people who have glucose problems, who have glucose spikes feel better. I’m so grateful that I have that very clear objective in my life because I think when you have purpose, you you feel happy, you feel you feel content. Of course, it’s very difficult. And as you build something publicly, you know, there’s a lot of negative downsides to it. But I also couldn’t imagine my life any differently now.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:06] Mhm. It feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:58:15] To live in your power and your purpose and in your truth. I think it’s a lifelong journey to get closer to who you are and how you want to create in this world, and to live a good life is to live a life where you feel like you’re authentically you. So if your passion is goddamn blood sugar spikes, you know, go for it. Make it your job. Make it your life. If your passion is knitting, if your passion is sports cars, if your passion is, you know, software engineering as much as you can live in that truth and that authenticity, I think the more happy and satisfied you’ll be with your life.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:52] Hmm. Thank you.

Jessie Inchauspé: [00:58:53] Thank you. Jonathan.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:56] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode Safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Aviva Romm about how our hormones influence our health. You’ll find a link to Aviva’s episode in the show. Notes. This episode of Good Life Project. was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and Me. Jonathan Fields Editing help By Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project. in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor? A seven-second favor and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life project.