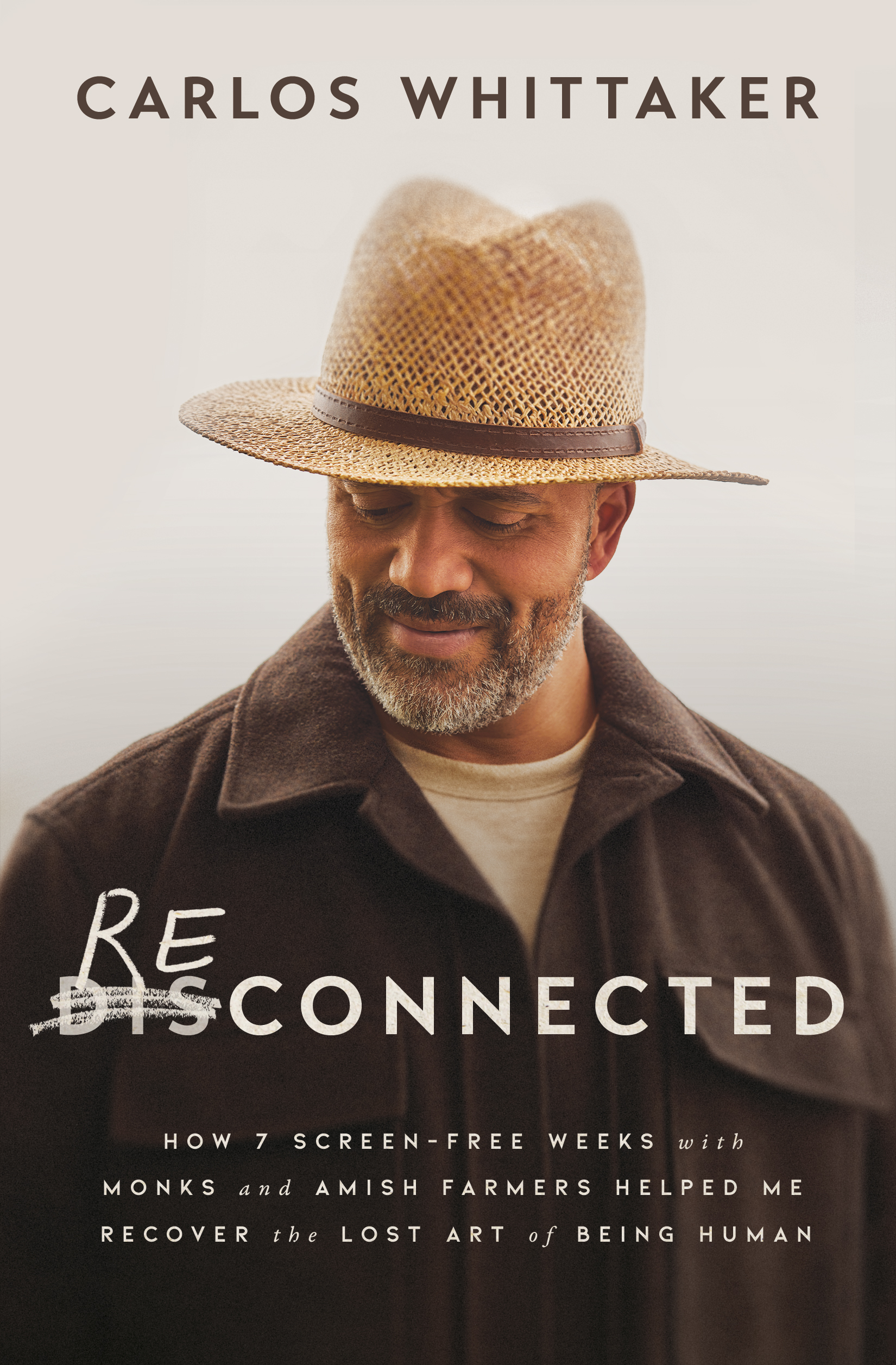

Time for a communal confession–our lives are lived around, and often, on screens. The typical person spends around 7 hours a day on screens, four and a half of that on their phones. Ever wonder what that was actually doing to you? Or, what was it was taking from you? Like, your relationships, your ability to be present, human even? Or, whether there was something you could DO about it, without becoming a hermit on a deserted island?Then you’re going to want to hear from my guest today, Carlos Whittaker. Carlos is an author, podcaster, and global speaker who has mastered the art of creating spaces for meaningful conversation. But when his screen time notification revealed he was spending a whopping 7 hours a day, or nearly 50 hours a week on his phone, he did the math and realized that came out to 12 years of his life staring at his phone if habits persisted.Carlos knew something had to change. His searching led him to run a wild experiment – spending 7.5 screen-free weeks living amongst Benedictine monks, Amish farmers, then screen-free with his family, while everyone around him still used screens, to rediscover what he calls “the lost art of being human.” In his book Reconnected, Carlos takes us along his transformative journey as he detoxes from the need for constant consumption, relearns how to embrace wonder and presence, and finds beauty in the seemingly mundane moments that true living is made of.

Time for a communal confession–our lives are lived around, and often, on screens. The typical person spends around 7 hours a day on screens, four and a half of that on their phones. Ever wonder what that was actually doing to you? Or, what was it was taking from you? Like, your relationships, your ability to be present, human even? Or, whether there was something you could DO about it, without becoming a hermit on a deserted island?Then you’re going to want to hear from my guest today, Carlos Whittaker. Carlos is an author, podcaster, and global speaker who has mastered the art of creating spaces for meaningful conversation. But when his screen time notification revealed he was spending a whopping 7 hours a day, or nearly 50 hours a week on his phone, he did the math and realized that came out to 12 years of his life staring at his phone if habits persisted.Carlos knew something had to change. His searching led him to run a wild experiment – spending 7.5 screen-free weeks living amongst Benedictine monks, Amish farmers, then screen-free with his family, while everyone around him still used screens, to rediscover what he calls “the lost art of being human.” In his book Reconnected, Carlos takes us along his transformative journey as he detoxes from the need for constant consumption, relearns how to embrace wonder and presence, and finds beauty in the seemingly mundane moments that true living is made of.

As someone who has grappled with my own struggles to unplug and be present, I was captivated by Carlos’ courageous leap into the unknown. His story, and his powerful insights, observations, and invitations serves as a much needed reminder that while technology connects us in so many ways, it can also disconnect us from our truest selves if we let it. And, there are very real things we can do about, without having to live in a monastery, or an Amish Farm.

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Tara Brach about dropping out of the trance of distraction and dropping into life.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Carlos Whittaker: [00:00:00] I spent 14 days with the monks, 14 days with the Amish, and then I spent three weeks with my family without a phone. My family got to experience some of the benefits, really, all of the benefits of what I’d been learning. And I will say that integration back into family life in Nashville life anyone can can not look at their phone living with monks and Amish, but get back into your real world. And that became more difficult, right? But my kids, man, they just. I’ll never forget my daughter looking at me. She was 17 at the time and her saying to me, dad, this is the purest dad I’ve ever had. And I was like, wow. Like, she’s just like, it’s you’re just so attentive. And I really love this. You know, it made me not want to turn my phone back on. I’d fallen so in love with again, with wondering and noticing and savoring and this lost art form of being human that I didn’t want the phone to take it away. We all have the ability to gain some of our life back. We all have the opportunity to do that. And why in the world would we not want to do that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:02] Okay, so maybe it’s time for a little communal confession. Our lives are lived around and often on and through screens. The typical person spends around seven hours a day on screens. Four and a half of those on their phones. Ever wonder what that was actually doing to you or what it was taking from you? Like your relationships, your ability to be present and be human even? Or whether there was something that you could do about it without becoming a hermit on a deserted island. Then you’re going to want to hear from today’s guest, Carlos Whittaker. Carlos is an author, podcaster, global speaker who has mastered the art of creating spaces for meaningful conversation. But when his screen time notification revealed that he was spending a whopping seven hours a day or nearly 50 hours a week on his phone, he did the math and realized that came out to about 12 years of his life, staring at his phone if his habits persisted. And Carlos really knew something had to change. His searching led him to run this wild experiment, spending seven and a half screen free weeks living with Benedictine monks, Amish farmers, and then screen free time with his family while they were actually using screens around him. And it was all about discovering what he calls the lost art of being human. In his book reconnected, Carlos takes us along his transformative journey as he detoxes from the need for constant consumption, relearns how to embrace wonder and presence, and finds beauty in the seemingly mundane moments that true living is made of, and that so often our devices and screens disconnect us from. As someone who has grappled really with my own struggles to unplug and be present, I was truly captivated by Carlos courageous leap into the unknown. His story and his powerful insights and observations and invitations. They serve as a much needed reminder that while technology connects us in so many incredible ways, it can also disconnect us from our truest selves if we let it. And there are very real things that we can do about it without having to live in a monastery or an Amish farm. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:29] I’ve been deeply fascinated with just how we as humans move through the day, and with how we react to technology to screens. What that does both to us and for us. I mean, you and I are having this conversation right now over technology. Awesome. Connects us in so many ways, and yet there’s so much out there as well. That kind of reminds us we have to really think about how we engage, not just default to autopilot. So you decided to do this really fascinating experiment. So let’s just set this up. Take me into this.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:03:59] Absolutely. I well, just so I’m grabbing so everybody knows, I spent seven weeks and I really seven and a half weeks and I never consumed from any screens. So like I never looked at an iPhone, Apple Watch, an iPad, a TV, a laptop, nothing. And I had my brain scanned by a neuroscientist before and after to see if anything would change. Um, and in the middle, I lived with 20 Benedictine monks at a abbey in the high desert of Southern California. And then I lived with an Amish sheep farming family in the middle. The whole reason I did this is because I wanted to know I was the perfect guinea pig for this. I wanted to know what a man that is on his phone seven plus hours a day. What is that doing to my head? And what’s that doing to my heart? On Sundays, we get that notification that many people do that slide across your screen that says you have averaged this many hours and minutes a day. And I’ll never forget when I saw that notification and I saw, you know, what I normally do is swipe it away and you just kind of, you know, you’re like, well, this is my job. It’s what I do. But I was like, well, I wonder what the math is. So I started doing the math. Seven hours and 23 minutes a day is about 49 hours a week. That was only the first equation I did, and I was like, oh, gross.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:05:15] Two entire cycles of the sun a week. I’m looking at these seven inches of LCD like, Holy cow! Then I kept doing the math and that equals about 100 days a year. And then if I live to be 85 years old, I think is was my math. Um, I’d spent over 12 years of my life looking at this and I just thought, okay, what is this doing to us? And so initially, it was going to be an experiment about a phone and an experiment about screens and experiment about, um, I think this, you know, this thing that we hold in our hands that I think I thought we were all addicted to. But, you know, Jonathan, it quickly turned into an experiment about all the other things that had nothing to do with the phone. All of the other things that I think we’ve forgotten how to do. And, you know, I say experiment loosely, right? Like like there was there was not a scientific experiment. I was the only lab rat. There weren’t other data points. But it completely revolutionized the way that I use technology, the way I consume from screens. And really, the way I do all the other things that I was reminded that we’re really good at doing off the screen. So that’s kind of where it all started, was that screen time notification. And off I went about a year after I got that notification. And I spent seven and a half weeks. Never looked at a phone.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:30] So most people get that notification also. And I get it. I do the exact same thing. I just I swipe it away half the time. I actually don’t want to know the number.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:06:38] Totally, totally.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:39] Like, I know if I actually start to do the math, like you were just saying, I’m not going to be a happy person when I start to add it up. And I would imagine most people just kind of like, you know, like it’s like, this is life. This is just what we do.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:06:49] This is life. Exactly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:50] You know, so when you decide to actually. Okay, I’m going to take seven, seven plus weeks and completely live without being connected to these different things. You could have used that time in so many different ways. You could have done so many different things. What goes through your head that makes you say, I’m going to spend a chunk of this time in a monastery, and I’m going to spend another chunk of this time on an Amish farm?

Carlos Whittaker: [00:07:12] Initially, I, I think what I wanted to do was be Ansel Adams and, like, go to Yosemite and live in a cabin and, and just kind of be with nature. And I quickly realized I probably would go insane. But like, the experiment wasn’t. I was like, I don’t I’m not trying to go insane here. I’m trying to see what screens are doing. So then I just started thinking, are are there any subcultures in America that I believe aren’t as addicted to screens as I am? And I just started thinking and I was like, well, I mean, my wife, actually, her father, um, when she was younger, was like a high capacity volunteer at this at this monastery. He would like help with their festivals. And he was friends with a bunch of the monks. And my wife was like, well, I mean, like, I knew these monks when I was three and four years old. So literally, that was kind of it with the with the monastery. My wife called the monastery and asked to speak to Abbot Francis, and she’s like, hi, my name is Heather Burkham, and my father used to. And he was like, oh, Heather, I remember you, you as a little girl. So she just said, hey, my husband wants to do this. And they were they were like, yeah, let’s go. Like 100%.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:08:20] Let’s jump in. He can come 14 days. So that was that part. The Amish was my idea because the Amish was like, I was like, okay, there’s some Amish that live near us here in Nashville about 80 minutes away in Etheridge, Tennessee. And we used to take the kids to go visit them. And I was like, babe, I think that’s where I want to live with, like, I want, I think I wanted like the the contemplative side of what this experience was going to be, I think at the monastery and then the kind of community driven side with the Amish. And so, yeah, I moved to Mount Hope, Ohio. The Miller family, a sheep farming family. And so that was like my purpose in choosing. You know, these two kind of subcultures, because I thought these would be two subcultures. That aren’t as addicted to screens as I am. And to be honest, like I had a lot of misconceptions. Of the Amish use of technology and even, you know, monastic life technology that I didn’t know that I was very surprised when I showed up in these two subcultures that, oh, they’ve got problems with screens, too. So it actually showed me that there’s some infiltration into even the cultures that we believe have no problems with this. Now. They’re they still are struggling. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:29] I mean, that would make so much sense. So you start out in the monastery, that’s really the first half of the experiment. Yeah. You show up on the first day like you walk in, you say goodbye, you’re like, okay, I’m here. What’s that first experience like?

Carlos Whittaker: [00:09:42] Oh, man. Oh my gosh, it was horrible. Like, let me just go and tell, you know, all of my introvert friends were like, oh my God. It’s like I would have loved it. 14 days. I’m like, listen, I don’t even care how introverted you are. I existed in 23 hours a day of silence with these monks. I knew that that was going to be the case going in. They put me up in this tiny little hermitage cat. One room cabin at the top of the hill overlooking the monastery. My best friend Brian is driving me there, and I’m legitimately having, like, heart palpitations. Like I’m I’m legitimately knowing, like he is about to drop me off and take my backpack, which has my Apple Watch, iPad, laptop, everything in it, and I’m just going to be left without any way to communicate, except for the monk phone that I would use to call my wife, you know, from their office. So the drive there was pretty nerve wracking when he left. I don’t think I’ve ever felt that alone. There was a sense of loneliness that immediately hit me that I had never felt before. And it was weird because I’m like, well, I’m not really alone. I’ve got all these monks around me. There’s other guests that are there, like, but it was it was pretty shocking. And when I say shocking, it was shocking to not only like my, I think, my emotions, but even physically it was shocking.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:11:00] Like, like when those first three days at the monastery were filled with physical manifestations of anxiety that I had not experienced in a long time, and I didn’t know what it was. I at first I thought I had the flu, like the first night, like I my I was like sweating at night. My bones were aching. I was like, oh my gosh, I’m sick. But then I wasn’t sick like the next day, like. And then it would just kind of come in waves, heart palpitations, tightness in my chest. And I quickly realized, not quickly, as 36 hours in, oh my gosh, I think I’m like detoxing. I think that my body is coming off of whatever this drug is, and I am having to settle into this new normal without all of this input that I’m constantly normally taking in. And so it was bad. It was tough. It was three days of hell, basically. And then it was day. I think it was morning for that. I just I’ll never forget it. I opened my eyes after like three days of like wanting to go home. I almost packed my bags and left. I was like, I’m going to write a book about 36 hours in a monastery. That’s all I need to know. Like nobody else needs to know. I’m addicted to my phone. I figured it out, but it was day four.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:12:09] I think that I woke up, and the only way I can describe it is it felt like if anyone’s ever had asthma and you’re having an asthma attack, and then you take an inhaler and you take that first hit, and then you go from like not being able to breathe to breathing. It was almost like that drastic of a moment where I was like, whoa, whoa, wait a second, is like it felt like an elephant stepped off of my chest. Is this what I’m about to enter into? Is this the the feeling of that maybe we were created to feel and that I didn’t even know that I was suffocating. But here I was. And so there was such a juxtaposition between day three and day four to where the first three days were miserable and all about thinking about my phone people that I’m missing, information I wasn’t consuming. And then days four through the end of seven and a half weeks, the experiment was no longer about a phone I had. I’d forgotten about the phone, and I’d started falling in love with all the things on the other side of the phone. So to answer your question, those first few days, it was very shocking. It was very disorienting, and it was hard. But I think I had to get through those first few days in order to experience the joy on the other side. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:19] I mean, the way you describe what happens on day four, it’s it’s amazing when we get reacquainted with this sensation in our minds and our bodies and our hearts that we probably felt when we were little kids. Yes, you know, but forgot that actually we can feel this way. Yes. And then we just move through life and we never really feel it feel it again. And then all of a sudden something happened. You’re like, oh wait, oh oh wait. As you’re describing that, I had this micro flashback to being actually in an ENT doctor’s office, and I had like a deviated septum and I couldn’t breathe through my nose. And he puts these little swabs up into my nose and it shrinks all the tissue and 60s later, I start breathing through my nose. I’m like, whoa, wait, wait, wait, what is this? What everybody else like, actually feels like? Yes. It’s amazing that so, so often, like, we kind of have to remove ourselves. Oh my gosh. And I wonder if you experience this also because it’s, you know, I think one of the challenges for so many people is we’re nodding along. We’re like, yeah, this sounds cool. This sounds makes total sense. And and, you know, we’ll talk about a whole bunch of other experiences you had. And people will say, yeah, oh, that sounds so cool. I would love to have that and feel that way. And then 30s later, we’re back on our devices or we’re back connected to people. And it’s like, it’s interesting that we as evolved beings in Things in theory like literally sometimes have to physically remove ourselves from all all, you know, possibility of temptation in order for that switch to be flipped? Yes.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:14:51] I mean, think about it though, right? Like anyone that’s addicted to anything. Anything. Right? You go to any 12 step program or whatever it is like, you have to legitimately remove yourself completely from whatever it is. And, you know, this is actually something that’s I don’t think I realized in this experiment, but I definitely realized it maybe a year after I got home, was talking about having to remove myself from any screens at all. Like, like just make sure they weren’t there. I think initially I thought that, well, we’re addicted to our phones. Like, like that’s the thing. I hear that all the time. Oh, my kids are addicted to their phone. My mom’s addicted to their phone. And about a year after I got back, and as I’m writing the book and as I, I realized, wait a second, I wasn’t addicted to my phone. My phone. This phone actually isn’t what we’re addicted to. The phone is the needle, right? Like a like a heroin addict. Isn’t addicted to the syringe and the needle? Obviously not. They’re addicted to the drug that’s going through it. And I realized while I was writing my book. Holy cow, the phones are just the needle. What is it that’s going through it that I need to remove myself from that? I actually and really quickly, I realized that my drug of choice was knowledge, which led to control this false sense of control that I suddenly didn’t have anymore. And I was detoxing from. And I think a lot of people, that is their drug of choice that’s coming through the needle, which is called the phone. And so how is it the question that we have to ask ourselves is, you know, because like you said, you’re right. Like, you could listen to this podcast, my conversation, our conversation and be like, yeah, this is great.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:16:28] Great. Like, you know what? I need to do this. Carlos Johnson says that we need to do this is great. And then next thing you know, you download some app on your phone to help you, but then you’re then you’re scrolling on Instagram because the ad gave you another thing. Next thing you know, two hours later in TikTok, you’re laughing and you’re and it’s like, well, yeah, you not only have to remove it, I believe, from your person. Like one of the things I help people do is like, start one hour on Saturday, go put your phone in the mailbox for one hour, put it in the mailbox, and then come back in your home. Now it’s nowhere near you, right? And then two hours the next Saturday and then six hours the next Saturday kind of work your way up to it. But also something that I realized was that no amount of locks on the liquor cabinet is going to literally break alcoholism, right? So no amount of locks on your phone or screen time locks are going to break you. What I had to do, and what helped me was actually just falling back in love. And we’ll talk about some of these things falling back in love with the realization that there’s all of these things in our humanity that we no longer do anymore, that are actually now more addicting for me to do than looking at my phone. I would much rather do all the things that I learned to do again than looking at my phone. And so I think that was also super helpful for me in breaking the addiction of knowledge.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:40] Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And I want to drop into some of those things. But before we get there, you brought up the notion of control and you know, like, okay, so this is this is a device or devices that help us feel like we are constantly having access to all of the information that gives us some sense of knowing what we need to know to control the world around us, and maybe the world within us. That kind of blows up for you, especially during your experience in the monster. And it’s really fascinating also. Right, because you’re also surrounded at the same time by a group of humans who have raised their hand and saying, I’m going to essentially withdraw myself from the householder life and surrender myself to something bigger than me. So take me deeper into sort of like your thoughts around control and how this experience affected you, and how how the experience of both being off of screens and also seeing the culture of the monastery influence your take on control.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:18:36] Goodness. First, I want to talk about how I think the the initial control that was brought to light for me was my control of my identity. It’s like suddenly like like I feel like, oh, well, I can control what people think about me by what I put across my phone for people to see. And that got taken away first. So that was kind of the first sucker punch that hit me. And I was like, oh my gosh, like these monks and these guests at this monastery have no idea who I am. They don’t know how many books I’ve written. They don’t know about my podcast. They don’t know that I know Jonathan, they don’t know any of this stuff. And so suddenly, like, I was building relationships from Jump Street, from Ground zero. Like, it was just like, okay. Wow. I didn’t realize how much control I had in putting forth some sort of, of identity for people to know who I was before I got there. So suddenly that’s taken away then, you know, I mean, so I’m a, I’m a, I’m in a spiritual place, you know, deeply religious place where, you know, it’s no secret to people that I am a deeply faith driven guy. And I guess I didn’t realize how much control I’d placed on what it is my faith. People can have different faiths and different beliefs that are listening to this. So put yourself in this situation for whatever your belief system is. So much of my belief system was built on what I was consuming for my phone.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:19:58] So much of the deep seated ideas of who I thought, you know, runs the universe and who I think God is. And all of these things were, were based on podcasts and apps and things that were on my phone. And suddenly when I didn’t have those anymore, things began to crumble really quickly. The thoughts that were invasive into my head, the the worries that kind of started coming into my head, the thinking about just how broken all of humanity is. And next thing you know, I’m like having a crisis. I am like in the middle of of a Of a crisis. And I think for me, you know, I find myself in, um, Abbot Francis’s office and I’m, like, pouring my heart out to him. And he’s like, I’m like, what do I do, you know? And it was just so cool because it was completely opposite of what I think maybe many pastor friends of mine would have told me to do. Like, here’s a book that you can go read or here’s a, you know, podcast to go listen to, or here’s something that’s going to help kind of rebuild what you’ve lost. He literally just said, I want you to go hike the mountain behind us. There’s a storm rolling in, and I want you to watch the storm roll in. That’s the thing that’s going to kind of reground me like, what are you talking about? And he goes, and I want you to behold.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:21:06] Behold was the word. And so I did. And can I tell you that when I climbed up there and I am like, kind of yelling out into the universe, like, what is real? Like, ah. And suddenly I just was like, there is something I don’t know what it is at this point, but there’s something much greater than I hear. And it was this beautiful moment of just allowing this beholding to begin to, I think, rebuild this false sense of control that I thought I had. I just I was controlling everything in my life. I was controlling life. 360 where’s my kids? Well, you know, when are they coming home? How fast are they going on the road? Oh my gosh. Like, I feel this weird sensation in my right arm. Like, I wonder if that’s something to do with the nerve. And now WebMD and control. Control like control is so much of what these devices give us. And when you take that away, what are you left with and how can you begin to navigate the realization that you’re actually not as in control as you really think you are? So, you know, I mean, you can read chapter five, six, and seven to find out the, you know, how I completely fell apart mentally and got put back together again by a couple of months. But, uh, it was definitely an incredible realization that, well, maybe I need to relinquish a lot more control than I’ve been hanging on to.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:21] Yeah, and which is terrifying on the one hand. But on the other hand, it’s like the reality of our lives is that we are not in control. Like there are some things like that we can kind of like, grasp at and that we can kind of lock down, but most of it is not locked down, but our internal and external experience. And if your belief system expands to something bigger, sure, then like that is a part of it also. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. One of the things that, and this is one of the things that you write about also during this experience is the relationship between control and wonder. I thought was really fascinating, right. Because when we locked down everything that’s locked downable. Yeah, it kind of excludes the space for wonder in our lives, which is like which also excludes one of the most wonderful things that we can experience. Right.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:23:11] Well, you know, I go into the difference between wondering and wonder and how, although there are two different things, they’re really interconnected. And I quickly realized how much these screens and honestly, Google in particular, or whatever search engine you uh, you would use, whether it be YouTube or TikTok, whatever, I call them wonder killers, because I quickly realized every time I wondered something, I would just pull my phone out and I would kill the wonder. It would be gone. And I realized while I was at the monastery and I started wondering, well, I wonder why the monks do this. I wonder why they do this. I would reach for my phone when I would wonder, and I just had to wonder. It was the craziest thing and I was like, whoa, wait a second. So I guess I’m just stuck in not knowing. And the not knowing led to some incredible conversations I had with some of the monks. The not knowing, the wondering led to all kinds of, I think, ideas in my mind, and I think that was one of my first realizations, was that, wait a second. I think that maybe we were created to wonder. We were created to exist in this wondering state. Which leads to wonder, right? So wondering leads to wonder. And then when we know everything, I just think we know too much. We just lose wonder. I just immediately go back. We may be around the same age, but I go back to like when I’m in high school, right? I go back to 1989, 92.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:24:44] And I just think if I had a question about something, I just would have to wonder about it. Unless I went to the library because my family couldn’t afford an encyclopedia set, and I’d go look it up and I’d get one paragraph that would help me answer the question. But that’s it. And now we just our souls and our psyche, I don’t think, were legitimately created to know as much as we know and to exist for seven weeks in just a state of wondering and wonder was absolutely mind blowing. So now when I’m with my friends and they hate it, trust me, and we’re sitting at a dinner party or something and you’ll hear it now, all the time. After you listen to this podcast, you’ll start hearing this. People around you will say, I wonder. And they’re actually not wondering, asking the question, saying I wonder isn’t wondering what wondering is. What happens after you? You say that and what happens is I wonder what happened like in 1987 when and someone will pull their phone out and I’m immediately the guy that goes, no, stop. We’re not going to find out the answer. I just want us to wonder. And everyone’s like, oh, but then that wondering leads to some incredible conversations. And so yeah, I’m like, I’m the I’m the wondering killer and hopefully the wonder bringer. Now, in my subset of friends.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:50] That I love, I’m gonna have to try that and see how many eye rolls I get. Yes. Oh, totally. Totally. You know, but this also brings up one of the things, again, this is one of the things that you sort of tease out in your experience in the monastery, this, this when you actually don’t have answers all the time, it also forces you to pay attention, and that forces you to start noticing things all around you that you know, when your head is tucked into a device, you just don’t you don’t. You’re not paying attention to our environment, to the people around us. And it’s like not knowing all the answers and knowing that you actually can’t get them by resorting to a device, it forces you to just start to scan your environment in a way that is really powerful. Yes.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:26:29] So powerful. I would climb back up to my. I say climb because like at the top of a little mountain, but my love to my little cabin every night just to watch the sunset. Like that was like my Netflix was like, sweet, like these incredible sunsets. And then, you know, the trees. And I was looking I just, I noticed so much. And we literally have, like, no opportunity to notice anymore because we’re just looking at these screens. And so my father used to always say gaze up and glance down. And I think we’ve got it switched. I think we gaze down and we glance up, and I do this little experiment at the airport all the time. I’ll count 100 people coming up the escalator, and I’ll see how many people are looking down at their phones and how many people are looking up. And inevitably, it’s always over 90 people that are looking down. And I just found so many, um, beautiful things that I noticed that I never. And that I begin to behold that I never would have. I think in the first place, you know, I tell a story. I don’t know if I tell the story in the book or in the documentary, but where I was walking from, like the bookstore at the monastery, back to my cabin. And, you know, I didn’t have a phone in my hand. So I’m just walking, looking around, and I noticed what looks like a cicada like in the parking lot, kind of buzzing. And I immediately, like, run away from it because I’m.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:27:46] If you live in Middle Tennessee, you’re terrified of cicadas, like you just don’t want to get near them. So I walk as far away as I can. But then I looked a little closer and I noticed that I was like, well, it’s not really moving like a cicada. So I get a little closer, and I realized it was a baby hummingbird that had fallen from its nest right into the parking lot. And so I noticed this thing. And so I was like, what do I do? And I remember thinking, like reaching in my phone in that moment, going like, because I need to Google, how do you rescue a baby hummingbird? Or like, what do you do? I didn’t have it, so I just had to like, figure it out. So I grabbed it and put it on a stick, put it in a thing. I had like two days of nursing this baby hummingbird back to life and waiting for its mom to fly down. And I never would have had this incredible two day experience with this hummingbird had I had a phone in my hand because I wouldn’t have noticed it. You know, I challenge people in the book, go on a walk around your neighborhood without your phone and without AirPods in. You will actually notice more about your neighbors, their yards, and things in your neighborhood that you never would have had you been consuming, as opposed to just existing and being and walking. And so yeah, noticing is a powerful, powerful thing that is slowly but surely becoming extinct.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:54] Yeah. I mean, it’s um, as you’re describing that. Also, I’m reminded of a conversation I had with, um, researchers Julie and John Gottman a couple of years back who run this, what they call the Love Lab. They’ve been literally researching relationships for 40 years. And in some of the research, they they basically say that one of the critical things that can determine the success or failure of a relationship is what they call bids. They say like all day, every day. We are all bidding for affection for attention. And there’s that. They’ve actually measured a ratio. I can’t remember the exact number, but like if you fall below recognizing a certain number of bids on any given day, it starts to actually signal the potential for harm in the relationship. Wow. And the thing is, if we’re just constantly buried in our devices, we miss most of the bids. And the research wasn’t even that like, you have to respond to a bid in a very particular way. It’s about noticing it in the first place and just saying, oh, hey, I noticed you need a little bit more coffee over there. Like, can I come over? It’s just about like seeing somebody actually bidding for your attention or affection and acknowledging that in some meaningful way, even if you can’t respond in the way they want. Right. It’s that noticing that leads to, okay, the goodness that comes out of it. So like you described like the the two days with the bird. Yeah. It never would have happened had you just been sitting there walking with your head scrolling on something ever.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:30:16] I would have missed so much. And I love about what you’re saying is like, it’s actually not even like because what you’re saying with the whole relationship thing, it’s like, yes, noticing is something, but we all want to be noticed, right? And so, like, there’s this innate desire to be noticed, to be seen. And even within conversations, we can tell when we are stopped, when the person we’re talking to no longer notices us, even while we’re talking to them. Right. Like even in the I had seven weeks where I never had a single buzz or ding or notification on my person that took me away from noticing the person in front of me. So I was fully invested in every single moment of every single conversation that I had with another person, because I didn’t have anything that was removing my noticing them to try to notice it. Right. And so, like even these notifications I think are like notice killers, they’re well, we’re supposed to be in one in one place staring at a person. You and I are having this conversation. A notification goes off and suddenly we’re, like, drawn to. Even if we don’t look at it for a moment in our brain, we leave the place where we go to an alternate universe. We think about what it is that this notification is, and then we try to get back to where we were. All of those things were gone during those seven weeks, and I was able to notice with 100% noticing skills the whole time.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:37] Yeah, I love that. And I think it’s often worse when we have a device in our pocket where we just set it to vibrate, right? But we’re like, I feel it in my pocket, but I’m here with this other person. I’m just going to focus on them. Yeah, but our brains at this point are wired to basically, the minute you feel that a portion of your brain now goes, what’s happening? What was that? Who was that? Was it. And until you actually, you know, actually check and release the stress that has now been caused by this, you’re not actually present in the relationship from that moment forward. And yet we feel like, oh, but we’re we’re honoring this conversation and we’re honoring the person we’re really paying attention. And and in fact, just having that device on you, it changes the nature of an interaction, I think, in a really big way. It really does. But we convince ourselves it doesn’t. You know, one of the other things that you, you talk about and that I thought was really interesting is, is noticing pace when you’re in a monastery, the pace of how things unfold is profoundly different than in life outside of the monastery. Take me into this a bit.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:32:40] Yeah. You know, I was so frustrated those first few days that everything moved so slow. I just these monks talked so slow. They chanted so slow. They ate so slow. And for the first few days, I was like, come on. Like, we got things to do. I want to, I want to learn to be a monk. Like I want to do this, you know? And what I quickly realized was like, I call it Godspeed. You know, we were all created to move. Every human being averages around three miles an hour when they walk, and three miles an hour is about the pace that the monks did everything. And what initially was frustrating to me is I was breaking through the cycle of, you know, addiction to consuming this knowledge and being in control. When that when I was still in that I wanted, I think because I lost the speed of content consumption, I needed something else to be fast. And when it wasn’t, it was. That was again shocking to me. Oh my gosh. But man, when again, it was probably day three. I learned to love to live at three miles an hour and I started realizing, gosh, it’s not even how fast we move. What other things in my life can I bring back to three miles an hour? There’s many things in our lives that we can control that we can slow down.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:33:56] I think so often we are told this. I believe it’s a lie that we’ve got to go faster in order to get the thing that we want. And I think I realized at the monastery, maybe if we go slower, will actually catch up with the thing that it that it is. We’ve been trying to find for so long. And that thing can be 1000 different things for 1000 different people. But that three miles an hour, that pace, which was the pace that I was walking when I saw the, you know, the hummingbird, it was the the pace that I walked when I would hike up to the mountain to learn to behold. It was everything was, I think, at the pace that humans were created to move. And we’ve just gotten so fast, like what in our lives really moves at three miles an hour besides our legs, you know, like really nothing. And so since I’ve been home, I have, like, purposely tried to implement a three mile an hour pace to many things that were no longer or that weren’t three miles an hour before. For instance, like my morning routine, what I loved about the monastery was that I think the first prayer chanting time with the monks was like 6 a.m., maybe 630, I can’t remember, but it was early and I would set my Mr.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:35:05] Coffee was like a like a 1985 Mr. Coffee Maker, and I’d set that thing with its little clock that you just push the little button, and I’d set it to start brewing at 5 a.m., and then I would just wake up smelling the coffee and guess what? I would wake up. I’d have my coffee. I wasn’t scrolling on my phone because I didn’t have one and I was just drinking my coffee. Can I tell you, friend, my coffee, that Dunkin Donuts breakfast blend coffee that I was drinking tasted so much better than my 995 vanilla latte that I get in my to go cup at Starbucks? Why? Because I’m just drinking it slowly. I’m taking everything so slowly. Now my mornings are just that. I no longer my phone’s not next to my bed when I’m at home because I’m trying to move at three miles an hour in the morning. So I plug my phone in in the kitchen when my alarm wakes me up because I bought this thing called an alarm clock, which a lot of people don’t even know they can buy anymore. But yeah, you can just buy.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:59] An alarm about that actually.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:36:00] What are these things? And that wakes me up. And then I just wake up and I try to have my coffee, just like I like I had it at the monastery. I go to my front porch and I just sit there and I just watch the birds hopping around in that cup of coffee tastes so good. And so I’ve just slowed my mornings down in order to try to implement as many three mile an hour moments into my day. Because if we’re not careful, what a lot of people say is life is speeding by me. My kids are growing up so fast. I’m like, actually, like time is moving the exact same as it’s always moved. We’re more than likely speeding by life. So I think slowing down is going to be the key to a lot healthier living.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:38] Yeah, I love that morning coffee ritual too. Yeah, I was thinking, like, the bougie hipster way to get coffee now is like, is the pour over? Right? Which forces you to actually wait, like 5 to 7 minutes, whatever it is for your cup of coffee. It’s so funny because people actually go and order this, which I mean, literally, it would give them a five minute window to just, okay, so like what happens if between the time that you order your pour over coffee and the time that it actually is ready for ready for you. What if just on a daily basis, you just committed to actually. Okay, so that window, that little window, I’m not going to look at my screen. I’m just going to sit here and look at the coffee shop, look at me or whatever it may be. And, you know, we order this intentionally slow way to prepare the thing that we have to have every morning. So then, like the second we’re done ordering, like our head is back in our phone until it’s finally ready and we can drink it, rather than using that as this opportunity to just plant a seed of just like slowing down for a moment, you know.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:37:36] And what a great example of just one way that you can make a conscious decision for five minutes just to be present and to live it three miles an hour. One of the things I no longer do is I no longer order coffee to go. If I’m in a coffee shop, I will only get it in a ceramic mug. And I think to myself, like, if I don’t have the four minutes it takes me to drink this coffee before it gets cold, if I don’t have four minutes to stop and I’ve got to take it to go. Then I’m moving too fast. So that’s another kind of little hack that I’ve put into my life that has slowed things down is I will only drink out of a ceramic mug. Just so everyone knows, every Starbucks actually has ceramic mugs. If you go to Starbucks, you can ask for your coffee in a ceramic mug and they will give it to you in that and just sit there and enjoy it and just be.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:22] I sometimes wonder whether one of the reasons that we move so fast also, is there’s a little voice in us that says if we slow down, if we actually like, dial it back 2 or 3 miles an hour, right, that we might actually realize in the slowness that the thing that we want and we’re striving for isn’t worth wanting, and then we don’t know what to do.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:38:43] Come on. I mean, that was probably day six. Mental breakdown for me at the monastery was exactly that. You know, it’s suddenly like you. You give yourself enough room to start contemplating just life in general. And just the bigger questions and just, you know, is this thing I’m chasing after? The thing that I really want to chase after. And also, knowing this, you know, I want everyone to also know, like, we’re not all called to be monks. We’re not all called to move always at three miles an hour, like monks. That’s what they they’ve chosen to do. I do not move at three miles an hour all day long. I’m still on airplanes. I’m still making YouTube videos, uploading things. I’m still doing all the things. But I’ve made a conscious decision to make sure throughout my day that there are moments of three miles an hour. And so I think just being conscious of that and making that decision is going to be one of the things that I think is going to open you up to a lot healthier lifestyle.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:38] Yeah, I mean, that makes so much sense to me. I want to bounce into the Amish experience a little bit also. But before we get there, there’s I think this is the last thing that you write about in the book, actually. It’s this notion of savoring, which kind of builds on everything that we’ve been talking about. Right? Because, yeah, once you actually allow yourself to be in a place of wonder, once you slow down, once you start noticing these things, once you actually sort of like allow your identity to unfold a little bit little bit differently. All those those moments, those sort of like micro moments that we just kind of blow past on a daily basis and don’t acknowledge and don’t actually say, oh, this is good. Yes. Like all of a sudden you’ve now created an opportunity for you to just take a hot second and say that thing that just happened to me. Yeah, that was good.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:40:19] I’m gonna I’m gonna savor it. I’m going to, you know, I talk about in the book how savoring doesn’t just have to happen in the moment that it’s happening. Savoring can happen leading up to it during the moment and after, upon reflection, you know, and savoring is something that I think also could quickly become a lost, a lost art form in our humanity. I think it’s the book where I lean into how you can get used to something good, and sometimes savoring means walking away from it and coming back so that you can taste it. Well, again, I give the example of if you ever walk by a bakery and you’re like, oh my gosh, like it smells amazing. And then you walk into that bakery and it smells so good, and you order your croissant. It smells so good. And then you sit down and you start eating it, and you actually forget how good it smelled until someone else walks in the bakery and goes, oh, it smells amazing. And then you quickly realize, oh my gosh, I can’t smell it anymore. And so what do you have to do? You literally have to walk back out. Stand outside for a minute and then walk back in. And then you can savor it again. So there’s all these ways that we can make sure that we’re, you know, savoring again, savoring more. But don’t think that savoring is just for the moment, like, anticipate, oh my gosh, what’s it going to be like when I’m taking my son to a concert? And we’re literally savoring it now before the concert even happens? Like, hey, what do you think he’s going to play the last song? We’re like, beginning to savor it. We’re going to get there and savor it. Then we’re going to talk about it afterwards. Like savoring is a whole thing. And I definitely think that’s something that that we have lost as well, that I, you know, relearned how to do when I was with the monks.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:49] Yeah. So agree. And positive psychologists talk about really interesting research around the experience of anticipation often being as nourishing, if not more so, than the thing itself. So they’re like, if there’s a great concert you want to go to, if there’s a vacation you are so excited to take, or an adventure and a journey you want to do. If you have the capacity to do it, book it not just a week or two before, but book it three months before. Because as soon as you do that, you plant the seed. You know it’s coming, and then you certainly bring it up and you’re like, ah. You keep sort of like bringing it into your mind. And the experience of just thinking about what’s coming actually is really yummy for a lot of people. I don’t remember how they measured yummy on this early positive psych scales, but and then the reflective savoring that you’re talking about, I think is is so fantastic also. So it’s not just the thing itself. There’s a window before and after that you get to bring this, this, this hit of smiles. Yes. Into your life. That’s really beautiful.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:42:48] Absolutely. No, it’s good. And I think it’s actually something that I think of, like when my dog got Ahold of our Christmas ham a couple years ago and like we left for, I think we walked out for 45 seconds, walked back in and the ham was gone. And I just remember thinking like, oh my gosh, like that ham was so expensive, but b I couldn’t wait to savor it. My dog did not savor that ham. He ate it as fast as he could, you know. And I think when we taste something that’s so good, we want to just consume it as much as and as fast as we can. But we as humans, I think we’ve got a, you know, a better idea of besides a dog, we have more control where we can actually, that’s why you want to really, you know, eat slowly like you want to eat that pizza so fast because it tastes so good. No, slow it down. I think this goes back to the three miles an hour. Three miles an hour allows you to savor as well.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:37] Yeah. So agree with that. I live in Boulder, Colorado, and um, so I’m in the mountains all the time whenever, you know, like, and I’m hiking with friends all the time when people come to visit, we’re hiking and, you know, we’ll go on a challenging hike and I’ll be with somebody, and we’re kind of just cruising along. And that my head is down and I’m just kind of like, okay, so I know this isn’t, you know, a two hour hike, it’s six miles. And, you know, I might flip open my alltrails and sort of like, see, where are we on the trail? And then I’ll get like halfway through. I’m like, it is gorgeous out here.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:44:10] Totally.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:11] And I’m not even paying attention. It’s like I’m hiking because I want to be in nature. And it is stunning out here. Yes. And I’m just sitting here tracking my progress on the trail.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:44:21] Oh my gosh, I’ve had so many alltrails moments like that too, where I’m like, oh my gosh, like, what’s my elevation now? And like, how far do we have to go? And that, you know, and it’s like, well, just look up. Right. Just look up, you know. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:33] And we’ll be right back. After a word from our sponsors. Let’s drop into into your office experience a little bit also because there’s a lot that continued through. But then there are also some really big differences, one of them being a really strong focus on community. I know, you know, you spend a whole bunch of time in a monastery barely talking to anybody, and then you, you drop into an Amish community and it’s almost like you go into the opposite world.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:45:03] Oh my gosh. I tell people, it was like moving from a cave to downtown Manhattan, you know? Mount Hope, Ohio, where I moved to, is a one town with a four way stop. But man, these people go. They go hard all the. I just remember, you know, spending that first day. And I farmed with Willis all day on the sheep farm. Listen, I’m a there’s no dirt under my nails. Like I’m a I’m a tech guy. Like I am not outside farming. And so I thought that the farming was going to be the thing that was going to wear me out. No, it was the talking. It was just nonstop communication, non-stop visiting with friends and and having every meal. There was different Amish people that would come over or they would go to there, and they just visited all day long and talk, talk, talk, talk, talk. And I did. I went to bed that first night so tired from like going from 23 hours a day of silence to like 23 hours a day of like, community and talking. And I think what initially wore me out was the very thing that I think I brought back with me from the Amish was just how well they love each other, how well they serve each other, how well they protect each other, how well they care for each other. It it’s the whole reason they exist. Like like community is it’s why they make the decisions with technology that they make. It’s every meal that we had was so long. 90 minutes, an hour and a half, two hours long. And and this was like, this is like our Facebook, Carlos. Like, I can’t read about what Farmer Joe’s doing every day. Like, the only way to find out is sit down and talk to him. And I was like, wow, this is actually what we were created to do and how we were created to live. And so, yeah, the Amish, the Amish was a pretty big whiplash as far as the two screenless environments, but fell in love with with what they taught me about community.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:43] Yeah. I mean, just the notion that you’re coming together regularly with so many people and also mealtime as you write about and describe and you’re just sharing a bit of it’s our everyday lives. Oftentimes it’s all grab and go or it’s, you know, we kind of we sit for as much as, you know, is the socially acceptable amount of time to sit in the family culture and then everyone books and does their own thing. Yeah. And then of course, half the time, like, you know, like everyone’s got their devices on the table during the whole meal anyway. And just the notion of, of having shared labor as a way to bring people together and then shared meals. Yes. As a way to bring people together and then taking your time, like the notion of lingering is what kept coming up for me. It’s like we don’t linger anymore. But this is like lingering is built into the culture there.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:47:30] Absolutely. It’s built into the culture. It I think one of the again, like I said, one of the most shocking things was how long every meal was. And in doing research for my book, I found a study that showed that in 1922, it was 22 or 23. The average American meal was 90 minutes long, and in 2022 or 23, the average American meal was 12 minutes long. And so you’re right, like it has completely been decimated. Just what meals are. You know, it’s eating now. It’s not meals. It’s we’re just eating and trying to get through it. And so yeah, I mean adding trying to add those things back into my life. When I got home with my family and, and my wife was a really important thing. But also the lingering piece, you know, they linger at meals, they linger in conversations while they’re working. They linger, they try to be around each other, whether it be family. They never do anything alone. I guess is is is really another thing. I guess I’m maybe I’ve never even said that before, but I realize, like, they’re always doing things together. And again, it’s all about community. It’s all about how they can be there for each other. Um, one of the things I learned from the Amish was that, you know, I think I, I used to think they thought cars were evil, like, I don’t know, like, that’s just kind of what I thought.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:48:41] And Farmer Willis, my little sheep farming Yoda, was like Carlos. Like. Like we don’t think cars are evil. The reason why we use horse and buggies and the reason why we are now allowing e-bikes. So it’s actually been crazy to watch the, you know, I show up and everyone’s on e-bikes, not in the horse and buggies. And I was like, what? What is happening? They’re like, well, e-bikes go about as fast as horse and buggies do. You can get about as far as a horse and buggy can without having to turn back around to recharge and come back home. The reason why we don’t have cars, Carlos, is because if Miss Sally’s barn burns down and I had a car and I was in Cleveland and Farmer Joe was in Massachusetts, and we’re all far away from each other like right now, we could all be back within an hour to whoever’s barn burned down, and we could have that thing rebuilt in three days. If we had cars, we would be too far away from each other to help each other. So the reason we don’t have cars is we want to make sure we stay close enough to serve each other. And I was like, whoa, how cool. You know? And so there there’s like purpose behind their decisions with technology. But all of those purposes go back to community. It’s community, community, community.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:47] I mean, that makes a lot of sense when you think about your time there also, and this is one of the things that you write about is it is sort of like your reflection on how the way that we live our lives and our deep connection to technology often affects our sense of intuition, and it affects in a really negative way, like if we’re constantly being bombarded by all the information we think we need from the outside world, we don’t even look for what insights or information might actually be just arising from within us anymore.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:50:21] Yes, we have all but erased our intuition. We don’t trust our gut anymore. The farmer, Willis, was trusting his gut every day. He wasn’t looking at the weather app. He wasn’t looking at, you know, any of that stuff to make his decisions on farming every day. One of the stories I tell is how I walked out one day. We’ve been trying to cut the grass, cut the hay for like seven days and days and like it kept raining and finally it dried. And then I knew that it had to be dry for us to cut it. And I woke up and there was thunder clouds. And I was like, oh no, like it’s going to rain again. And Willis was like, no, it’s not going to rain. Look at your boots. And I was like, what? I looked at my boots and he’s like, there’s dew on your boots. If there’s dew on your boots, it’s not going to rain. And I just thought, oh my gosh, this honest dude like this is horrible. Like, what a horrible way to make a decision. Like it’s look at the lightning strikes just a mile away.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:51:10] Like and sure enough, you know, like he made the decision because there was dew on my boots to cut the hay and it didn’t rain on his property. I’m sure that doesn’t work 100 times out of 100 times, but he used his intuition and it just got me thinking. We just we’ve lost that. We we want to go to a restaurant in town and we trust Bob, who gave it two stars on Yelp. He Bob is now making our decision on if we’re going to go to this restaurant or not. I’m like, Bob doesn’t even have my taste buds. Why am I trusting Bob on Yelp to give me a me a recommendation like I should use my intuition. Intuition is, I think, something that we actually have to exercise again because we’ve lost so much of it. We trust our devices way more than we trust our intuition and our gut. And the Amish really taught me about intuition and how to maybe reestablish some of that back in my life.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:00] It’s interesting the way you’re sort of talking about intuition also, because, you know, you’re not just saying, well, it’s a feeling I have inside of me, like the story you just shared about the farmer, it’s like, no, it’s also a way of gathering information that exists outside of you, but differently through observing, you know, through that noticing through that observing through that, wondering that you were talking about and saying, oh, I’m looking at different things that just occur naturally all around me and then my body like, and then I’m probably listening to the signals within me also that say like, yes or no.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:52:31] It’s like I have to remind myself, and all of us included, that there was a time that we were all alive, where we were not gathering information from these screens in our pockets. We were We were literally having to navigate with out Siri telling us in 800ft to turn left. We had to use our gut. You know, I’ll never forget Wallace asking me to go to the feed store to pick up a part for his tractor, and him starting to rattle off directions before I got on a bicycle, and me thinking to myself, is he expecting me to remember, like, all of the things he’s telling me to do? And he was like, of course. And you know, and I got lost and I, you know, would would have to ask people. I was supposed to say, oh, you made the wrong turn. And next thing you know, I’m like, wow, we’ve even lost like our, our ability, our I think human navigation skills to. And so like I begin to redevelop those things and yeah you know like intuition is just something that I think is especially for this for a generation that’s coming up. Right. Like you and I had we had to rely on our intuition a lot more than our kids.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:53:30] Our kids don’t even have to rely on it anymore. They’re just, you know, you got ChatGPT. You can just ask it a question. No more intuition involved. And I think we have to show them how beautiful intuition is. How beautiful it is to really rely on. Like you said, this isn’t just some internal dialogue. It’s being directed by external circumstances and by other data points that are coming in. Like, it’s not like intuition is just like flying blind and being super conspiracy theory person. No, like, intuition is actually a uniquely human thing that I think we need to, you know, get back in touch with. What are ways that we can get back in touch with our intuition every day. Maybe it’s looking up the directions before you go somewhere and just trying to remember it, and then seeing if you could figure out, oh gosh, I can’t remember where to turn. I think it’s this way, turning that way. And it’s okay to get lost. You know you can find your way. Trust me, you won’t get lost forever. So, yeah. What are ways you can find your intuition again?

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:25] Yeah. I’m even thinking of cooking. You know, like, what would happen if you tried to do that thing that you always do, but, like, didn’t use a recipe and just kind of, like, smelled it and tasted it and just kind of felt like what feels right or what feels good.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:54:37] So good.

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:37] You’re gonna have some really bad tasting stuff along the way, but at some point you can have some. Some miracles also. You’re like, wow, this is awesome. And like, it just came out of me. And which is super fun. So when you reintegrate after this experience because, you know, at some point this has got to end. Seven plus weeks later. Like dropping back into the family. Right. What’s that first 24, 48 hours like for you?

Carlos Whittaker: [00:55:00] Yeah, I well, so so everyone knows I spent 14 days with the monks, 14 days with the Amish. And then I spent three weeks with my family without a phone. My family got to experience some of the benefits, really, all of the benefits of what I’d been learning. And I will say that integration back into family life in Nashville life anyone can can not look at their phone living with monks and Amish, but get back into your real world. And that became more difficult, right? But my kids, man, they just. I’ll never forget my daughter looking at me. She was 17 at the time, and her saying to me, dad, this is the purest, you’ve Purest dad I’ve ever had. You’re just so pure. She’s the word pure. And I was like, wow. Like she’s just like. It’s. You’re just so attentive. And I really love this. You know, it made me not want to turn my phone back on. You know, I existed for three weeks with my family, with. No. When they now they had screens, they were still on their phones. They were still watching Netflix. I would just leave the room if they turned on the TV. We did go to Yellowstone for a week just so that they could experience some of this screenless time without me, but when I got back my phone, you know, I went I went back and we could talk about my brain scans later.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:56:08] But when I after my second brain scan, I get my phone back. I did not want to turn it back on. I probably spent four days and didn’t turn my phone back on. I had it, it felt like a brick in my pocket, but I was like to do what I do. I know I’ve got to turn like to make a living. I’ve got to turn my phone back on. Like, what am I going to do? And I’d fallen so in love with again, with wondering and noticing and savoring and intuit all of these things that that I talk about in the book, all these beautiful parts of this lost art form of being human, that I didn’t want the film to take it away. And the here’s the here’s the beautiful thing. I was at 7.5 hours a day on my phone. I’m now 3.5 hours a day. So it’s been two years since I did this experiment. I’ve gained four hours a day back of my life. Right? Like, so you start doing that math. And if in 12 years, that’s almost a year of my life that I’ve that I’ve gained back. So just know that as difficult as it was to turn my phone back on, I know I needed to do it. I realized very quickly, there’s beautiful things on this phone that that we can do.

Carlos Whittaker: [00:57:10] There’s beautiful things on these screens that this conversation that we’re having. It’s going to help a lot of people. I really again realized that the phone is the needle, and I just needed to manage what it was that I was ingesting, what it was that I was that was putting back into myself. So, you know, those first few days of my phone being on, I did something most people wouldn’t do. I, I can’t remember how many thousands of unread text messages I had. I just had select all delete. I just deleted them. I didn’t even look at one of them. I was like, if someone needs to get hold of me really badly, they’ll they’ll come back at me. So yeah. So, you know, it was hard. And there, you know, there’s weeks where I’m, I’m back on my phone six hours a day if I’m launching a book and I’ve got a project coming out like this experiment wasn’t about why phones are bad. It’s why falling in love with what’s beautiful on the other side of the screen is so beautiful. And those are the things that have kept me off my phone. Um, it hasn’t been, you know, locking it up and putting a padlock on it. It’s been. No, just wondering, not needing to find the answer. All of these beautiful things have kept me off my phone.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:07] Um, I love that. Years ago, I had the opportunity to sit down with, um, who was then the greatest living, uh, designer, Milton Glaser. Oh, wow. And he was in his mid 80s, still working at his studio, as prolific as ever. But he didn’t work with computers, but he had computers in the studio, and he had a small team of people who were using those computers all the time. And what he would do was effectively, he would do a lot of his own work. And then as they would sometimes help, sort of like express that digitally, he would work with them, often standing behind them while they were on the computer, directing them like he was very conscious of needing a particular boundary. He said, I understand the value of technology in this process, yes, but I also think there’s a boundary that I need to create just for me to do the thing that I need to do in the way that I know I need to do it. And it was such a powerful it was like this really subtle, just passing moment as he was walking me through the studio. But it has stayed with me because I was like, wow, this is a guy who was at the absolute top of his game. He’s been doing this for, you know, like literally 60 or 70 years at this point. Yeah. And producing just stunning, stunning work. And he’s like, he’s doing this dance in a way that actually is really intentional and thoughtful. And I thought that was really fascinating. It’s kind of what you’re talking about. It’s like, okay, let’s just figure out how do we do this in a way that’s healthy for us?

Carlos Whittaker: [00:59:26] Yes, yes. And what’s healthy for me is me is going to be different than what’s healthy for you, but also knowing that we all have the ability to gain some of our life back. We all have the opportunity to do that. And why in the world would we not want to do that? You know, I just challenge everyone to do the math. Just do the math. You know, like like just pull out your screen time right now when this is over, pause or whatever and just start doing the math. See how many hours a week. Multiply that by whatever you need to to figure out what how much time in a year you’re spending. And that is all it’s going to take for you to be like, okay, I’m going to buy an alarm clock. You know, like like what? What are the things that, that you can do to even buying an alarm clock will average will give it a normal American and on average of an hour back of their day, just an hour, because we spend 30 minutes before we go to sleep, and 30 minutes after we wake up scrolling, just buying an alarm clock will normally wipe that hour out.

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:20] Mm. Amazing. It feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. Um, so in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Carlos Whittaker: [01:00:30] Wow. Gosh. To live a good life for me is to make sure that my family feels seen by me, and that I feel seen by them, and whatever I can do to make that happen is what I’m going to try to do.

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:45] Mm. Thank you.

Carlos Whittaker: [01:00:46] Yeah, absolutely.

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:49] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode, safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Tara Brock about dropping out of the trance of distraction and dropping into life. You’ll find a link to Tara’s episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help by Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or Interesting or inspiring or valuable. And chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here. Would you do me a personal favor? A seven second favor and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.