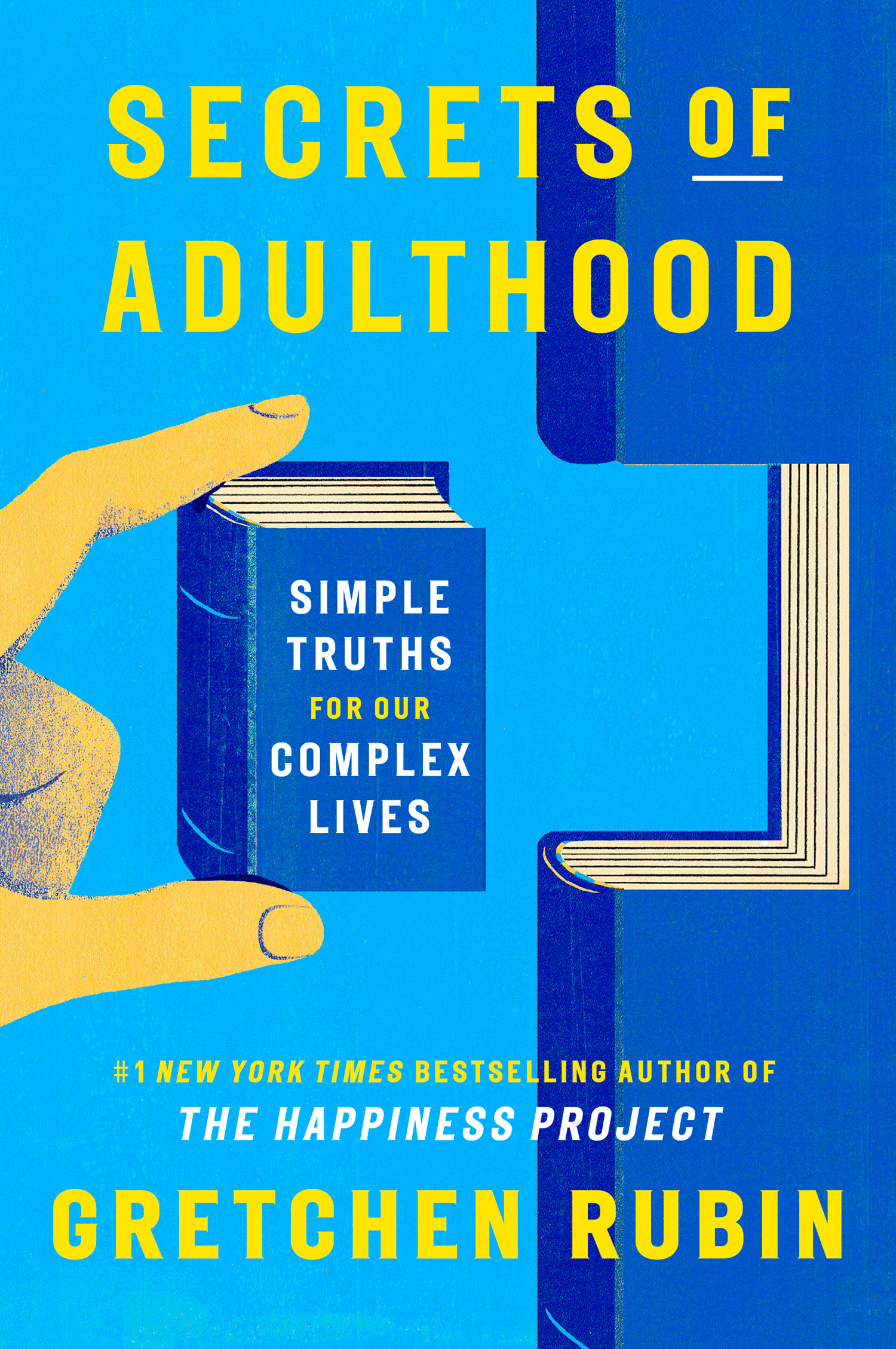

Have you ever felt like you’re overthinking the “right” way to live a fulfilling life? In this insightful conversation, happiness guru Gretchen Rubin, author of bestsellers like The Happiness Project and her latest, Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives, shares profound yet practical wisdom to help guide you through life’s inevitable dilemmas.

Imagine having a collection of powerful aphorisms – succinct sayings packed with perspective-shifting insights – at your fingertips. Rubin’s “secrets of adulthood” illuminate paths to cultivating true self-knowledge, nurturing meaningful relationships, making things happen, and confronting challenges with grace.

You’ll discover surprising truths like: why building your own happiness can ironically make you unhappy in the moment, how the words you use shape your reality, and the counterintuitive key to better judgment (hint: it’s not just accumulating more facts).

Whether you’re yearning for purposeful work, deeper connections, or a fresh outlook on life’s puzzles, this conversation offers an intriguing roadmap. Walk away with inspiring nudges to craft your own profound personal mantras – potent reminders to light your way through complexity.

You can find Gretchen at: Website | Instagram | Happier with Gretchen Rubin – Podcast | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with James Clear about habits and identity.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

- ADHA Aha! is a podcast hosted by Laura Key that explores pivotal moments when people realized they or their loved ones have ADHD, sharing both touching and humorous stories of ADHD discovery. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

photo credit: Austin Walsh

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Gretchen Rubin ACAST.wav

Gretchen Rubin: [00:00:00] And it’s so important because we can only build a happy life on the foundation of our own nature, our own interests, our own values, our own temperament. So, so much goes back to well, it depends on.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:10] Gretchen Rubin is a leading voice on happiness, habits and human nature, and the best-selling author of The Happiness Project and so many other books. Her newest book, Secrets of Adulthood, distills decades of insight into concise, life-changing aphorisms that guide us through life’s complexity.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:00:27] One of the best ways to make other people happy is to be happy yourself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:32] It’s one of those things where there’s a tension in this.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:00:34] There is a tremendous tension. Yes, and maybe you don’t agree with it. One of the ones that I love is there’s no right way to create a happy life, just like there’s no one right way to cook an egg, because people would always say to me, how should I become happier? And I would say, but we skip this step.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:55] When I saw that you had I’m going to use the word finally come out with a book of aphorisms. I use that word finally because I remembered immediately, like a million years ago, you and I, hanging out in our sort of like regular cafe on the Upper East Side in New York City, and you telling me how you had this just, like, lifelong interest and passion for aphorisms. And I’m nodding along and I’m like, oh, it sounds really cool. And you’re sort of like, there wasn’t talk about a book at that point. And I remember sort of like going home and googling what is aphorism.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:01:30] Yes. You’ll notice that that word does not appear in the title or the subtitle of.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:34] The book.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:01:35] Because a lot of people do not know what an aphorism is.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:38] Yeah. And then I remembered and this was probably like in the very early days of our friendship, it must have been like 2010 ish. I think it was right around before, maybe before even you came out with The Happiness Project, that you came out with a video. Um, that was this aphorism, and I remember that exploded. It went like wildly viral. And that was the one around.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:02:00] The days are long, but the years are short.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:02] Right? And I was like, oh, right. That it contains so much wisdom, so much information, so much curiosity in this like short, tight thing that it just doesn’t take any time. So one of my curiosities, before we dive into just a whole bunch of the different aphorisms that I think are really fun and have so much value is what’s the difference between an aphorism and a, for lack of a better word, a platitude.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:02:32] Right? Well, you do see different definitions of different things, but in general, in general, there’s there’s two kind of gateway distinctions. And one is like a proverb is something that is just folk wisdom. It’s something that is floating around, but it’s not attributed to a specific person. And often these will fall into the category of platitudes because they’re very familiar. And sometimes they might be invoked in ways that seem kind of like superficial or shallow. So a platitude might be something like the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence, which, by the way, is factually true because grass will look greener if you see it from a distance than if you look down at your own feet where you see all the brown and the discoloration. So that’s literally true and figuratively true, or something like try to think of the glass is half full instead of half empty, whatever. Again, the glass is full. It’s half gas, half liquid. Okay. But these these are sort of, I would say proverbs that almost are platitudes or they are invoked in platitudinous ways. An aphorism is something where it’s attributed to a specific person. So Oscar Wilde said it, or Dolly Parton said it, or Warren Buffett said it or Mantegna said it. And these could also be platitudes if the person says the platitude. And so I guess a platitude is just something where it feels like an observation that’s kind of sentimental or shallow. So with my aphorisms, I tried to be original and profound, but it’s like everybody has to be the judge about whether they are truly insightful or whether they fall into the category of platitude.

Jonathan Fields: [00:04:08] Okay, so if you’re then sitting down with the task of writing your own aphorisms and trying to make them original and profound, how do you know, like when you’re sitting there, just sort of like jotting out ideas and ideas and ideas and ideas and ideas. And I would imagine that over the years you’ve probably done like thousands of these thousands.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:04:28] Yes. My document is so gigantic.

Jonathan Fields: [00:04:31] Yeah. So how do you look at those and say which one of these is actually genuinely in some way like profound and original?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:04:39] Well, part of it is just judging by my own experience, because all of these are sort of secrets of adulthood that have meant something to me that I feel like I’ve learned the hard way. So sometimes things are pretty obvious and that you’re like, yeah, but it’s like, you know, you could say working is one of the most dangerous forms of procrastination now. That’s pretty obvious, but it’s like I remind myself of that at least once a week, sometimes once a day, right? Because working is one of the most dangerous forms of procrastination. So a lot of it is I just went by the ones that felt helpful to me as I went through my life or something. Like we care for many people we don’t particularly care for now. Is that a profound insight? I’m not sure. Is it something that’s useful to remember and maybe like seeing a big idea distilled into a single sentence like that kind of makes it you can grasp it more easily because it’s said in this brief way. And I did have so many. So I really picked the ones that I felt really rose to the level of of being what I hope would be really interesting and useful. There’s a lot on the cutting room floor for this.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:47] One, I.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:05:47] Would.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:47] Imagine. Yeah. Um, so interesting and useful. It’s kind of like the metric that you were using there.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:05:52] Yes, because I had a whole I had a whole bunch of aphorisms that I would call merely observations. So something like the periodic table of the elements is an ingredient list to the universe, which is kind of true. It’s not 100% true. But, you know, it’s kind of an interesting idea. It’s an interesting way to think about it. Or the tulip is an empty flower. I believe that the tulip is an empty flower, but it’s just an observation. There’s really nothing to do with it. Yeah. So with this, because I framed it as Secrets of adulthood, I really wanted it to be like, is this something that could help you deal with other people, make decisions, get things done, understand yourself better. Like, have that element of helpfulness, not just observation.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:32] Yeah, I think I love that because I feel like so much of what we do read, like a lot of 1 or 2 liners, we’re like, oh, that’s interesting, or that’s kind of cute or that’s like, I never thought of it that way. Yeah. And then you kind of move on because there’s actually beyond like just a momentary passing fascination. There’s no utility in helping us make decisions and like, change your behavior or take actions. So I like the frame that you bring to it, which is like this actually has to guide my behavior in some way, shape or form. It has to help me when I’m at a moment and I’m making a decision.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:07:03] Exactly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:04] And like, oh, this drops in. It’s like right, right, right. Okay. That helps.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:07:08] And some of them are observations, but they’re meant to be sort of like insights into something that’s important to keep in mind. For instance, the bird, the bee and the bat all fly, but they use different wings. Now that’s actually, I think, really interesting. I was super excited that I had like an alliterative set of three examples that all did have completely different kinds of wings. But that’s a reminder that just because something works for Jonathan doesn’t mean that it’s going to work for Gretchen and vice versa. And it doesn’t mean that we can’t all do what we want to do. We can all fly. We can all get to the top of the mountain, but we might have to take a different path to get there. And so again, that’s just like trying to frame that observation, which, I mean, I’ve written whole books basically that are just exploring that idea in some kind of succinct way.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:50] Yeah, I mean, that makes a lot of sense to me. So when you sit down and you write a book, you kind of divide your list of like, all right, these are my my top ones here into four major categories. But then also at the end, sort of like a general like this is a whole list of a whole bunch of general, you know, like secrets of adulthood.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:08:06] The funny one at the end. So those are simple secrets of adulthood. So, you know, I love a hack. You know, like, I’m happier with Gretchen Rubin. We talk about hacks all the time. I love just like a simple trick to be happier or healthier, more productive, more creative. They did not rise to the level of what I would hope to be would be a major insight into human nature, but they were still useful. Like to keep in mind. And so I just couldn’t help myself. I threw them in at the end and I thought, oh, my editor is going to take them out because she’s going to say, Gretchen, you know, you’re getting off task here. You just this is just like your personal love of these things. But she said, no, you know, they’re really fun. Let’s just put them in at the end, and they just kind of add a different level of a secret of adulthood. And then there’s even room for people to write their own secrets of adulthood. Because my hope is that as people go through this, they’ll be thinking like, well, you know what? I’ve had kind of a similar idea myself, but I put it a different way, and I would like to write it down. Yeah. Yeah. So some of them are bigger ideas and some of them are just sort of more practical, smaller ideas.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:01] And I do want to circle around to the idea of writing our own at the end of this conversation, because I think a lot of people.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:09:06] That’s very much your kind of jam.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:07] Jonathan, be really cool to kind of like create my own set here and like, how do we actually go about it? So we’ll circle back around to that. Let’s dive into some of these because some of them are really fun. Like we’ll start out just with the opening category here, which you define as cultivating ourselves. And there are a whole bunch of subcategories. We’ll kind of cherry pick a little. And maybe if there’s if there are ones that really just like you’re like you love that jump out at you. Like feel free to share too. Well, first let’s talk about the categories. So cultivating ourselves, why is this a category that you felt like okay, so this needs to be a pillar in this whole exploration.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:09:39] Well, the thing I’m sure you’ve seen this yourself, Jonathan. Like, if you’re studying happiness and well-being and how to create the life you want, you have to begin with self-awareness and self-knowledge. And it seems like this should be so easy, right? We just hang out with ourselves all day long. What could be more easy than knowing myself? And yet, this is a great challenge of our lives. And it’s so important because we can only build a happy life on the foundation of our own nature, our own interests, our own values, our own temperament. So, so much goes back to, well, it depends on you. And so I was like, okay, this is going to be a category and it should be the first category. Because really this is the basis for a lot of other things that we think about doing in our life. But but it’s going to be a much easier and more productive to do those things if we do it from a place of understanding ourselves.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:28] Yeah, I love that. And of course, you know, I completely agree. And it’s also, I think the single biggest missed category in our like we get there, we’re like, right, how do we live a better life like all this different. And we’re looking for all the things outside of us and nothing is changing the way we want it to change. And we’re like, what is happening here? I’m doing all the things. It’s like, oh, wait, I’m not doing any of the inner things right?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:10:49] And I’m cramming myself into somebody else’s model. That may be right for me if I’m lucky, but probably isn’t quite right for me. And I’m going about it in a way that’s a model for somebody else and not for me. Right? But we skip this step. This is well, one of the ones that I love is there’s no right way to create a happy life. Just like there’s no one right way to cook an egg, because people would always say to me, how should I become happier? And I would say, I can’t tell you that. That depends on you. And they would become really frustrated and just and then I would say, well, what’s the best way to cook an egg? And they would say, well, I don’t know. It depends on how you like your eggs. And some people say, well, I don’t even like eggs. It’s like, right. So I can’t tell you the best way to cook an egg. Only you know that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:11:31] Yeah. And that is one of those things where everyone’s looking for the universal magic pill. It’s like, just give me the thing that works for everybody.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:11:38] The most efficient way doesn’t exist?

Jonathan Fields: [00:11:41] No. You and I have been both deep in that exploration for a lot of time, and.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:11:45] Well, and I started by thinking that you really could have the best way in the right way. Like, I thought that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:11:50] That.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:11:50] Was going to be my major, my major mission. But, you know, if if it were really that simple, everybody would, would just do that thing. But no, we all we all have to figure it out for ourselves.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:01] Yeah. So let’s dive into a couple more of these. Under this category of cultivating ourselves, the opening kind of subcategory here was the project of Happiness. Mhm. And this is a really long aphorism. Happiness doesn’t always make us feel happy living up to our values, challenging ourselves, facing our mistakes, depriving ourselves. These aims make our lives happier, but don’t always make us feel happy in the moment.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:12:24] Yeah, well. And really, I would consider the aphorism to be happiness doesn’t always make us feel happy, because that’s sort of the big idea. Yeah. Some of these have a little bit of description or kind of a illustrating example. Tried to hold back as much as I could. Right. Because I think, Of course, of course. If you’re a scientist and you’re studying happiness, you have to be very precise with your definitions. There are like 17 academic definitions of happiness. But I think for the average person, like, you know, you get it. It’s whatever, whatever joy, peace, contentment, well-being, life satisfaction, whatever you want to do. But the fact is, if you have a life where you want to be happy, you’re going to do things that don’t make you feel happy. They’re going to make you feel insecure. They’re going to make you feel sad. They’re going to make you feel uncomfortable. You’re going to have to deprive yourself of doing something that you want to do, or make yourself do something that you don’t want to do. That is no fun. And yet, that’s all part of a happy life. Living up to our values often involves being in situations that don’t make us feel that happy when they’re happening, but they’re part of a happy life overall.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:30] Yeah, I mean, that really resonates with me. I remember years ago I heard from, um, an expedition guide. He’s like, and maybe you’ve heard this categorization before, he said, we categorize fun as like there are three types of fun. Yeah, like level one fun is the fun where it’s it’s just fun. You’re happy. You’re having a great time when you’re in it. Level two, it’s a little bit miserable when you’re in it, but upon reflecting back on it, it’s really, oh, that was great. Level three, which I never quite understood this. He’s like, it’s not fun when it’s happening and it’s not fun when you’re reflecting on it. I was like, how is that actually still considered fun? But apparently it’s how they categorize it.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:14:05] Yeah, there’s something called the effort paradox, which I guess which is sort of related to this. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:10] That’s interesting. All right. You shared in our setup also, um, this one, another short one. One of the best ways to make yourself happy is to make others happy. And I think this is a really interesting example, right. Because on the surface, you’re like, oh, sure. Like that makes a lot of sense. But then if you dig deeper, you start to think, does this actually depend on the person? And I think the answer is probably yes, because you may have people who literally wake up in the morning and their drive is to just serve, serve, serve serve, serve. Others. Others. Others. Others. Others. And. And that drive leaves them gutted over a period of time. So, like, this one was interesting to me because it kind of speaks to the fact that there’s the the surface obvious level one. But then each person is this is going to land differently for them depending on who they are and what they’re thinking about. For some people, they may be like, I’ve been doing this my whole life and it has destroyed me.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:15:03] Um, but that’s why there’s a second part to that aphorism. Yeah. One of the best ways to make other people happy is to be happy yourself. And so if you’re if you’re worrying so much about making other people happy, that you’re not happy yourself, that’s also not good. So I think we have to remember both of those. And that’s where it gets confusing, because people sort of overindex on one side or the other. One of the best ways to make yourself happy is to make other people happy. One of the best ways to make other people happy is to be happy yourself. Because there’s no one that well, and this is a bleak aphorism that I didn’t include. I left out all my bleak aphorisms. So I’ve got a whole collection of those.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:46] Totally should have had a chapter that was like my bleak.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:15:49] You know, it’s funny because everybody keeps saying, this is the this is the negativity bias. Everybody’s like, I want to know the bleak aphorisms. Right. But one of my bleak aphorisms is something like, nothing is more dismal than pointless sacrifice. And we’ve all been around people who it’s like they’re going around like helping and sacrificing, and you’re like, you know, we’d all wish you’d just kind of take care of yourself for a little bit, you know? The tension between those two principles, I think, is one of the great challenges within happiness.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:21] Yeah. I think that’s so true for so many people. Um, and I feel like so often we default to the opposite mode when we it’s like, that’s a very interesting point. Right. We’re struggling. We’re suffering. We’re like, oh, I need to really focus inward. I need to take better care of myself. And maybe that’s part of it. It is so often I mean, the research shows that actually especially part of the suffering is sort of like a neurotic spin and chatter that like when you become other focused, it actually helps lift so much.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:16:55] Yes, yes. Yeah, yeah. No. The Dalai Lama has this great passage where he exactly explains that. No, but so that’s why I think both are true. We’re happier when we’re doing things to make other people happy, but we’re also making people have they’re happier people when we’re taking care of ourselves. You know, that’s put on your own oxygen mask first. It’s also the principle. Or, you know, what the research shows is that happier people tend to be more effective in the world. They’re more interested in the problems of the world. They’re more effective in helping other people. So sometimes people think, well, if I worry about my own happiness, that just means I’m smug and complacent and self-centered. But in fact, research shows that happier people are more likely to vote. They’re more likely to donate their time, energy, or money. They make better leaders and better followers. They’re better kind of friends and family members, you know, because they’re happier. They have more emotional wherewithal to turn outward and to think about the problems of the world. But it’s also true that what you just said, one of the best ways to make yourself happy is to think of others and to, you know, take action in the world and to try to do things that are going to be for the benefit of other people, and that helps you forget yourself. So both of these things are true. They they aren’t they they seem to be in tension, but they actually work together. But I think you’re exactly right. We often kind of insert ourselves on one side and forget about the other side, to our detriment.

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:16] Yeah. Do you find that there’s a common tendency in aphorisms that you can look at them in different ways and find different truths?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:18:23] No, the best aphorisms. I kind of have multiple levels of meaning, and they often will use paradox, um, or kind of reversal the way that one does. Because, because again, it’s trying to use a very short form in a way to really spark insight or also just even reflection, because I think with a lot of the aphorisms, people might really disagree. People might very much disagree with this aphorism. But even then, I think because it’s something short and kind of powerful to contemplate, we can think to ourselves, well, do I agree with that or do I not? And kind of it shows us our own thinking. And so I think that they can often just by being thought provoking, they can often reveal to us our own conclusions, even if they’re different, that’s still valuable. I mean, like Oscar Wilde has a lot of aphorisms that he tosses off and I’m always like, huh? I wonder if I agree with that? But it’s like, that gets me thinking in a new way.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:13] Yeah.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:19:14] And so they often do have, uh, multiple meanings or like one of mine is like, if you don’t like a pair of pants, don’t pay to get them hemmed. It’s like, okay, that could mean a lot of different things. And it can mean exactly what it says.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:27] Right? Right, right. You can get you can get, like, five layers deep.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:19:30] Yeah. You can take that take. Make of that what you will. Right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:34] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. It’s an interesting way for you to sort of, like, inquire into yourself.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:19:42] Exactly. Exactly. Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:45] It’s also, I think they can be really interesting touch points for conversations with other people.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:19:50] Mhm. Right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:51] Because like you can be like so how does this land with you. Like and and it really helped I almost look at this as a book that you could pass around as sort of like a dinner party or people who don’t know each other yet and have everyone like just offer one out. Yeah. And have people kind of like debate, like, how does this feel to you?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:20:05] Oh my gosh, that’s my fantasy. Like how great as an author like that somebody would do that. Yeah. But I think you’re you’re really right. And it also taps into this idea. And Jonathan, I know you’ve had people tell you this like there’s a proverb that when the student is ready, the teacher appears. And sometimes it’s just like, you just need to come across the right idea at the right moment. And it could come from all different places, but it just hits you at the moment where you need to hear it and it can change your life. And Jonathan, I know your work has played that role for people. It’s tremendously exciting and it’s sort of like sometimes you sort of want to put yourself in the path for insight. It’s like, how do you put yourself in the path for insight? You know, it’s not so easy. And so again, it’s you hope that that a few of these might be really fun, really thought provoking. It spark conversation and that it might, for somebody, be like the one big illumination that shows them kind of their way forward, or reveals to them what they’ve thought all along, but never really quite put into words and so weren’t able to be guided by it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:04] Yeah, it’s like it gives them language for what it’s been spinning in their head for a long time.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:21:07] My, the best aphorism, I think, is the one where you say to yourself, oh, I’ve known that myself. I recognize that, but I just never really stopped to put it into words. That’s the most satisfying kind of aphorism.

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:19] Agreed. Okay, so along those lines, under the category of self-realization, Realization. We know if something is important to us, if it shows up in our schedule, our spending and our space. Okay, so I’m nodding along with this. And then how often have you or anyone sort of like joining us done some form of values exercise where they’re like, okay, so like here’s a list of a million different things like pick the five things that are like your values, the things that are most important to you. And you pick your five things. And then it’s like, are you actually like is the way that you’re showing up in your life making clear that these are the like five most important things to you and the choices in your behaviors? And for most people, the answer is no. So this is one of those those things where it seems obvious on the surface, it’s not showing up in my schedule and my spending or my space, but we’re like, but I really do believe that these things are important to me.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:22:09] Well, and I think this is I mean, talking about the idea that it’s sort of hard to know ourselves. That’s a good way to sort of use external clues, to give yourself insight to what’s going on inside. Because if you say like, well, culture is a really high value for me, but you don’t spend any time going to concerts, going to movies, going to productions, going to shows, going to museums, going whatever it is culture for you, you know, and you don’t engage with it in any way. It’s like, well, maybe you need to do more of it, or maybe you need to reevaluate what you think your values are. Or if you say, family is really important to me, but if it doesn’t, if family doesn’t show up a lot in your schedule, your spending and your space. Well, there’s a variance between what you say your values are and what they seem actually to be as lived.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:01] Yeah, I like that you delicately use the word variance there.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:23:05] I hope I’m using it correctly. That’s slightly. That’s a slightly. As I was using I think I’m pretty sure I have that right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:11] Yeah, I agree with that. And I think, you know, it’s one of the again, that’s one of those things where it just makes you stop for a second. You’re like, okay, so sure, like this makes total sense to me. And then it’s like, am I doing this in my life?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:23:22] Am I doing this in my life?

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:24] I say that these things are important to me, but if somebody from the outside looked at the way I’m living my life, what would they like from that same list of like, like 500 different things? What would they pick out just observing me and put on that list? And does it match up? And it’s like, oh.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:23:41] You know, that would be so interesting if you had a thing where you posted it and somebody was like, and then there would be some kind of analysis being like, okay, what are the evidence based values that somebody objectively would infer looking at the evidence? That’s fascinating. Oh, see, Jonathan, you’re turning everything into. You’re like, how do we turn this into an instrument?

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:06] We need to actually make it something bigger.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:24:08] We do. But I do think this is it’s the kind of thing where you’re like, yeah, if a private investigator was going to be, like, studying me and doing, like, a character profile on me, what would that person conclude? You know, here’s a funny thing that I often do, and I don’t know where this comes from, but I have this weird fantasy of, like, if my husband vanished, you know how like, there’s always like, these thrillers or like somebody just vanishes. And I thought if somebody looked at our text chain like a private investigator, what would they think was the truth of our relationship? Right. Because, again, that’s the kind of evidence. What does our text change show? And so every once in a while I’m like, I’m going to put in some hearts. So the private investigator knows how deeply I love my husband. Right. Um, and my husband knows too.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:50] That’s too funny.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:24:51] Here’s another example. A friend of mine who moved to California, he’s like, oh, I moved to the beach because everybody who moves to California says, oh, I’m going to go to the beach all the time. I love the I love the beach. I love the ocean, I love to surf. And he goes and they never do. They never go. And he said, I just know that that’s true because I’ve just talked to so many people who say that. So I’m going to live on the beach as close to the beach as I can, because I really do want to surf, and I wanted to be a big part of my life. So he put it in his space. He put himself in that place because he’s saying, no matter what people say when they move to California, when they moved to Los Angeles, they don’t follow through. Yeah, a lot of that has to do with Los Angeles traffic, but that’s the fact of it, right? So he he made sure to put that into his space.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:34] Yeah. That makes so much sense to me. And I’m somebody who like five years ago moved to quote moved to the mountains. Right.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:25:39] Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:39] And like leaving my home, New York City for three decades of my adult life, basically my entire adult life, to go to this, like, new place. And we made a decision, we were like, okay, so we can be right up against the mountain where I can walk out my front door and be hiking literally in minutes. Yeah, or we can be 20 minutes out. We can be able to actually walk out our front door and have this gorgeous view, see the entire front range of the Rocky Mountains, which is just breathtaking. But then I’m going to have to get in my car and drive 20 minutes every time I want to hike, right? And like, I knew that wasn’t going to happen.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:26:13] Um.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:14] So it’s like, why would we move 2000 miles away to move to the mountains? Yes. And have that like 20 minute difference basically annihilate everything that was, you know, that I wanted to do on a daily basis.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:26:25] That’s another one of my bleak aphorisms. Convenience always wins.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:29] Yeah, that’s not bleak. That’s just real.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:26:32] Well, that, you know, maybe. Maybe. But but I think that I think that that is absolutely fascinating. And so, yes, like, do you undercut a gigantic decision with a small decision. And this comes back to self-knowledge because somebody might be like, oh, well, what I want to do is be within a 20 minute drive of a hike and a ten minute drive of like a town where I can go to a bookstore and a coffee shop. And so this, for me is the perfect thing because I. No problem. I’ll just I’ll ride my bike to the hike or whatever. But you’re like, hey, I know Jonathan pretty well because I’ve thought a lot about this. And yeah, we better have it right outside our back door. Again, there’s no right answer or wrong answer. There’s no best way to do this. It’s like what’s right for you?

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:15] Yeah.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:27:15] What’s true for you? What are your weaknesses? What are your interests? Like what matters? It sounds so obvious, but like, that is such a perfect example. You move across the country and then you’re like, 20 blocks in the wrong direction, right? Amazing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:29] I just know myself well enough. I’m just, like, especially in the winter, you know, I’d be like, I am not getting in a car and driving 20 minutes to go freeze for an hour and a half. Whereas like, for some reason, if I can walk out my front door and do that, I will. It just takes one more piece of the puzzle away that stopped me from doing it.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:27:47] Exactly, exactly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:48] The next big bucket that you focus on facing the perplexities of relationships. Yeah. Why were you like. This has to be its own category.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:27:57] Well, ancient philosophers and contemporary scientists agree that if you want to make your life happier, you have to have strong relationships. We need enduring bonds. We need to feel like we belong. We need to be able to get support. And just as important for happiness, we need to be able to give support. We need to feel like we can confide. And so relationships are just if you’re thinking, well, what are the secrets of adulthood? One of the secrets of adulthood is relationships are tremendously important. They deserve a huge amount of our time and energy and understanding, but they are perplexing. Here’s a bleak aphorism. My mother always says everything would be easy if it weren’t for people, you know? And it’s like, yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:40] Okay, I sometimes agree with that.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:28:42] Yeah. But, you know, but people are the hassle and people are the fun, right? Right. You got to have the people. And so how do you manage the people, given that the people you want them there. And so that was why there’s a whole section on the perplexities of relationships.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:56] Yeah. No, I love that and completely agree. And I actually want to float one that you already teed up in our conversations, one of the early ones, you know, we care for people we don’t particularly care for.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:29:05] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:06] Take me into this a little bit more.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:29:07] Yeah. I mean, I think again, this is sort of a paradox, but I think it’s really true where we can care very deeply about people that we don’t particularly care for, like we don’t enjoy spending time with them, or we disagree with them profoundly about important matters or values, or we’ve drifted away from them over time, and we’re not really interested in picking up a relationship. And yet we do care. We do care for them. And so it can be kind of confusing sometimes to be caught in that. And I think it’s clarifying to realize that, yeah, you can care for people that you don’t particularly care for.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:47] Yeah. I thought it was interesting to me as I read it, a variation immediately popped into my head.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:29:52] Ooh, I love a variation.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:53] Which was we care about people we don’t particularly care about.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:29:59] Ooh. Oh my gosh, Jonathan, I love that. We care about people we don’t particularly care about. Oh, that is 100%.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:07] Because it’s kind of like the definition of social media.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:30:09] Like. Ah. Yeah. Or like celebrity gossip. Right? You’re like.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:13] All that stuff.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:30:14] Yeah. I don’t I don’t particularly care about whatever. I love it, but see like now in the back of the book you can write that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:22] Exactly.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:30:22] And then again, like, this would be a super fun thing to debate because I never thought that about that. And now I feel like I’m going to think about it every day. We do care about people we don’t particularly care about.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:35] And it was so funny that that popped into my mind as soon as I read that. And maybe it was just sort of like the moment that I was in, you know, I was like, oh, wait. Yes. And like in my context, I was thinking more about social media. You know, how so often, you know, there are just all these people and often all these strangers? Yeah. And we care about their perception of us.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:30:59] Well, that’s an see, these are multiple meanings because one meaning is here’s this Hollywood celebrity. And I love reading about the gossip, but I don’t really particularly care. But another one is somebody gives me an online review of a book and I say, well, I don’t really care and I don’t really care. And yet it I really do care. It really does get in my head. So it’s like there’s a double meaning there.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:24] Yeah. And all based on your original one.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:31:26] There you go.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:27] So friendships you write about under this category. Also, it’s better to invite friends over for takeout than not to invite friends over for a home cooked meal.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:31:36] It’s better to do something badly than to do nothing perfectly. It’s funny because I’m in a book group where we take turns hosting people and like serving dinner. And I always say to people, I’m the bottom of the curve. Like, everybody feels like, well, I don’t do much, but neither does Gretchen. Or like, I don’t do much, but I’m doing more than Gretchen does. And I’m like, that’s me, you know?

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:56] So you’re like the book group slacker, basically.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:31:59] Well, I’m a book group. I’m like, high conscientiousness in reading and slacker in dinner presentation.

Jonathan Fields: [00:32:06] Got it.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:32:06] And nobody cares. Nobody cares. That’s the thing. What they care about is, like, let’s hang out and talk about books. So it’s better to have the takeout than to say, like, well, I’m not going to have people over if I can’t do it, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:32:22] Yeah. I mean, it’s such a great way of also, in my mind that translates to, you know, like, what about this thing actually matters? Like what’s the heart of it, you know, and all the like, don’t throw out the heart of it just because you can’t get the trappings the way you want them to be.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:32:38] And the thing is, for many people, it is a joy to entertain. And they love the process and they find it deeply satisfying creatively. And so for them, it serves many purposes, and it just doesn’t do that for me. And that’s fine, you know? And so I again, it’s back to self-knowledge, which is we’re still arriving at the core of it. And if somebody else is also getting this other this for them, it’s a whole other fun thing. Well that’s great.

Jonathan Fields: [00:33:03] Yeah. Really does all go back to self-knowledge. Um. More friends, more safety. This was interesting for me because I was like, I haven’t really thought about it that way.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:33:13] Mhm. Well, it’s interesting because I just read this big research report that came out for like the World Happiness Summit did it, and they were looking at young people specifically and relationships and happiness. And so they were they really were focused on young people. But I think it’s true for everybody that that if you’re looking at life satisfaction, quantity, quality and structure matter for happiness. And so really having more friends really does protect us from loneliness. It makes us healthier. Um, strong ties and loose ties do a lot to, like, plug us into the world and to give us access to information that we need or resources that we need. They can give us valuable advice. Like if you have friends of different ages, that’s something that can really contribute to happiness. If you have friends at different ages and stages because they can like be sources of wisdom and guidance for you, and you can be a source of wisdom and guidance for others. And that’s also a source of happiness. It’s interesting. My sister Elizabeth was lives in Encino, and so she was there recently when there was all the wildfires. And, you know, and it was it was this really fast moving emergency, but it was kind of hard to figure out for each individual household, like what exactly is happening to us.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:34:22] And she said she was in a couple of text chains and in one text chain, they said, okay, if you have to go stay in a hotel, here’s a good hotel that takes dogs. So she had a piece of information that like something that might have taken hours and like been this frantic search was easily solved. And then somebody else had a relative who was a first responder who was like, oh, actually, if you go to this checkpoint in Encino, they’ll let you in like they’ve opened up that. So she knew that like hours and hours before kind of the, the official announcement made its way into the world. And so these more friends, more safety, like how to flee, how to return all these like really she was in a life and death situation, sadly. And having these friends, having these relationships really gave her safety. But then it’s also our social safety, our emotional safety of feeling like people have my back. There are people I can trust if something important happens, there are people I can confide in. There are people who know me. There are people who, if there’s an emergency, will go feed my dog. You know, this gives us a feeling of comfort and reassurance and safety.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:30] Yeah. And I think, I mean, it’s so true. And yet I never really thought about it that way, which I guess is part of the point of of an aphorism like this. It’s like it allows you to think of something that’s been in your life for like, yes, the whole sweep of your life. And then you see it differently. You’re like, oh, there’s a different value equation that doesn’t replace my old one, but it adds to it in a meaningful way, especially if I’m in a moment in my life where I’m feeling psychologically or emotionally or physically unsafe. I’m like, huh.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:35:56] Right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:57] This gives me another option.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:35:59] Yes. Right. Exactly, exactly. That’s where the secret of adulthood comes in.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:04] Yeah. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. Perspective is something where you share some thoughts. Also, the setup in this particular category was longer and I’m curious. It felt like you wanted to give more attention to the notion of perspective.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:36:23] Mhm. Yeah. Yeah. Because I’m constantly surprised by just the perspective that we take on something really matters. Reframing matters I used to just think like well reality is reality and the facts are the facts. But really our perspective makes a huge difference in our conclusions, our emotions, just how we feel about something. Sometimes, like the most simple and obvious reframing can make a gigantic difference in how we understand what’s happening to us.

Jonathan Fields: [00:36:53] Yeah. And I mean, one of those reframes is one of the aphorisms you offer under this By changing our words, we can change our perspective. Like you and I are both writers, we’re both deeply into words. It really is interesting how by simply shifting the language that you’re using, whether spoken or written, it can really shift the way you think about something.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:37:10] Well, I’ll give you some examples from my own life. So lifelong dream. My husband and I got a lake house and it’s so exciting. And there’s a room in there that has some built in bookshelves and a desk. So the question is, what is that room? Is that room an office? Is that room a study? Is that room a library? And I’m like, this room is a library. And whenever anybody else calls it anything else, I’m like, oh, are you talking about the library? Because I’m like, the library is an amazing room that I love to hang out in the office. That doesn’t say I love to work, but even to me, I’m like, I’d rather be in the library than in the office. It’s the same room. And then another friend of mine, he in his house in the suburbs, he had this kind of funny little room. It was sort of the dumping ground where it had kind of a bunch of different things in it, and everybody just sort of put stuff in there, and they called it the dump zone. And now he’s trying to. And because I love to clear clutter. Of course, I’m like happiness bullying him about this. And I was like, what are you going to call this room because you’re calling it the dump zone. And that’s what people are doing is they are dumping stuff in it. If you’re going to clean it out and reshape the use of it, call it something else. He’s like, well, maybe we’ll call it the Social Room, but then he and I wordsmithed it and they’re calling it The Game Room.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:24] Oh.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:38:25] Because a game room is like, it’s social, but it’s active and it’s like you have to have things cleared out if you’re going to play a games, right? Because you have to have a surface to play poker or we’re going to like, you know, play canasta or somebody’s going to play the guitar. It’s a game room. And so anyway, those are kind of very basic examples. But I think show like even with something very simple, you know, you’re playing piano or practicing piano, they feel different.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:52] Yeah, totally. Um, third big category for you is making things happen.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:38:57] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:38:57] And like this immediately got translated in my mind to work. But it doesn’t have to be work. And by work I mean like your j-o-b or however you earn your living.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:39:07] Yeah. Because a huge factor in a happy life is the sense of efficacy. It’s the feeling that you can want to do something and do it. And I think that is a really big challenge in adulthood, which is just getting things done. So I thought, okay, that’s a major section.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:23] Yeah. And it’s where so many of us spend, like we’re we open our eyes, we’re like, what are we doing? Yes. You know like.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:39:29] Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:30] One of the things you share under this, where we start out makes a big difference in where we end up. This became really detailed in my life out here, because when you’re a hiker and you’re in Colorado and you’re this part of the country, often people talk about these things called fourteeners, mountains that are 14,000ft or above, and there are something like 60 plus of them just in the state of Colorado. And like a lot of people, will be like, I’m on a mission, you know, on a ten year quest to hike to the top of all the fourteeners. So I was asking a friend who’s done all of them, like, what should I start at? And he’s like, well, I recommend this one particular because you basically drive up to about 9000ft and then it’s like, so like it just it really brought home this one particular aphorism like where you start out literally like, I could be going from where I live now, which is 5500ft. Or I could be going from, you know, like starting at 10,000ft.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:40:25] Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:25] And either way, at the end of it, I come home.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:40:28] Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:29] I get to, like, write in my journal and tell my friends I did a fourteener today.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:40:33] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:35] Totally different experience.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:40:37] I love the way these are literally illustrated by your life in Colorado. This is great. Yeah. No I mean that’s a perfect example because you’re not lying if you say that you did it. But where you start out makes a very big difference in how you end up, which is like, how do you feel at the end of that climb? It’s like it’s very, very different. Yeah, and I think I also think of this sometimes, sometimes we say like, well, it doesn’t matter what you just do anything. You can always change your mind later, but you know, where you start makes a difference in where you end up. And like things kind of take on a life of their own or you learn, you tend to go deeper. Once you’re in it, going in a direction you tend to, you don’t veer as far away from it often. And so yeah, I think that’s true in many ways.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:21] Yeah. And I think this also speaks to the reality of how if you just look at it more broadly in the scope of people in life, in work, in opportunities and possibilities, that we don’t all start on the same starting line.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:41:36] Exactly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:36] And for like one person, it might be really easy. For another person, it may be ten times harder to get to the exact same job, same title, same outcome, start a business. And it acknowledges the fact that okay, so don’t just look at the finish line.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:41:51] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:51] Like when you’re considering these things either for yourself, really consider where you’re starting and also for those around you. If you’re in the habit of comparing.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:42:00] Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:00] Don’t think you know where they started until you actually have the conversation.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:42:04] Exactly. Exactly, exactly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:07] Yeah. Um, the thirst for knowledge, um, under this, the more we know, the more we notice. I love this. I’m not sure why I just did.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:42:17] Well, you’re you love curiosity. Yeah. It’s just the more you know, the more you notice. It’s just really, really true. You know, I go to the Metropolitan Museum every day. I started doing that for my book, Life in Five Senses, and I enjoyed it so much I’ve never stopped. And one of the things that I know is like, if I’ve read up on a painting or like there was an art, like there’s a new exhibit and there was an article in the paper that really highlighted something, or I learned about it in a class, or sometimes I’ll read a novel where it will talk about an artwork or something. I just notice it more. I can look at it longer. I appreciate it more when I walk by it. Later, it jumps out of the wall at me. And the more we know, the more we notice.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:00] Yeah, in my analogy on that is um, is music also.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:43:04] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:05] And more when I was a kid than now, like when I grew up, this was the time of liner notes.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:43:10] Yes

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:10] An album and you have all these notes and stuff like this. And I remember just listening while I’m reading all about the music that I’m listening to and the people in it and the stories behind it, and you notice so much more in the music when you actually know where it came from and the people and like what they were working towards and what they were like, the stories that they were looking to tell in the music. It made me pay attention more. Even having just the most basic stuff. And I started doing this also in museums. I used to go to museums, and I would just look at the stuff on the walls And ignore the little placard next to each one of those things that shared a bit about what it was. And then I was like, okay, it’s nice, it’s pretty. Whatever. Um, and then I started, you know, like taking my time and slowing down and reading the placards and then stepping back and looking at the work. And I was like, oh, this is a very different experience.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:44:04] Yeah. No, it really it’s true. And I think that’s why we do love to learn about the things that we enjoy, because you just enjoy it more. I mean, maybe you listen to football podcasts because you love football or right, you watch interviews with great musicians because you want to have more insight into their music. I mean, there’s so many ways to do it. And I think that’s part of why is like, it’s just we have a richer experience when we know more. Um, back to that lake house. I said to somebody, oh, I love it because there’s all these trees all around. And they said, well, what kind of trees? And I thought, I have no idea. I have no idea because I cannot, I cannot identify a tree. I a pine tree, maybe, but I don’t know. So then I was like, okay, I’m going to get an app. And every time I go, I’m going to try to identify like learn to identify a particular kind of like tree or flower or, you know, whatever. And um, and it is interesting, like you just you notice like, oh, it’s oh, you know, why is it that this one street has all these and like, oh, can I tell the difference between a spruce and a fir and all that? You just notice it much more.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:12] Yeah. And then it’s like this benevolent cycle of noticing and knowledge. Right. Because then the noticing brings more insight and information into you, which then allows you to notice more.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:45:23] And then more curiosity, because then you’re like, huh? That’s strange. How did that get here? How do you explain this thing? Or like, wow, this this album is completely different from all the other albums. Like what was going on there? It makes you want to go deeper and deeper and deeper.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:36] Yeah. Um, under this category too. And it’s sort of like the subtopic of creativity. Putting materials into our hands often puts ideas into our heads. As a physical maker, I was like, oh yes.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:45:49] Well and the thing that’s funny is, and I learned this from Life in Five sense, my book, Life in Five Senses, because in Life in Five Senses really showed me the importance of the hand putting things in the hand and how the hand is so connected to the brain. And one of the things I found, and I often recommend to people who are feeling sort of creatively stuck, is just go to someplace where there’s a lot of materials, physical materials, and it doesn’t even matter if those are the physical materials that you know how to use. So, like, I never cook, but I could go to a big like cooking store that had all kinds of like devices and implements and pots and pans and all this, or a hardware store that’s or like a home supply store where it’s like you could build anything, you know, you could do anything in your home with this, or an art supply store where it’s just you just walk up and down and there is something about just and you like, put your hands on in the barrel of screws, or brush your hands across the brushes tops and it just somehow prompts creativity. There’s just like a spark between like materials, hands, and creation. It’s really powerful.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:54] Yeah. And I’m I’ve so noticed this. And oftentimes if I feel like I’m stuck with something, I’ll, I’ll find a way to work with my hands.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:47:02] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:02] And even, like, even if I’m, like, working on something writing wise. Right? And it’s just kind of not flowing.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:47:07] Right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:07] And then I’ll go and I’ll just do something where I’m working with my hands. And that somehow unlocks the writing, which is really interesting. Like, it doesn’t just unlock the creativity in the context of what you’re actually physically making. It does something to my brain.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:47:21] Well, it’s interesting also on that point. So on the On the Happier podcast, I was sort of proposing this new thing that I had noticed, which I was calling the Rule of More. This is like a new idea. It’s not a new idea, but kind of a new way to think about it. Which is, the more you do something, the more you do it. So, like, the more you exercise, the more you tend to exercise, the more. And because my sister, who’s a TV writer, was saying that the more she writes, the more she writes. She just started a Substack and she’s saying, like, actually writing regularly for the Substack is actually helping her TV writing. Like, just the more you do, the more you do. And some a listener wrote in and said, I found that. Yeah, exactly what you’re saying, Jonathan, which is it’s not even 1 to 1. It’s like if you’re creating with words more, it might make you create with paint more, or if you’re working with paint that might unlock something with your writing, which is just this doing tends to like get our energy flowing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:12] Yeah, absolutely. So the final bucket that you dive into here is confronting life’s dilemmas, which of course, I’m surprised all the bleak ones didn’t end up there, actually.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:48:22] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:22] Tough decisions. I thought this was really interesting. Um, one, it’s easier to enforce rules than to be fair.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:48:28] Mhm. Every parent knows that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:31] Ah, right. I mean that land is kind of like with a thud. But it’s one of those things where there’s a tension in this.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:48:37] There is a tremendous tension. Yes. And maybe you don’t agree with it. You know what I mean? Because I went back and forth on that a lot. I was like, is that true? Do I agree with that? But I do feel like it’s true.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:50] Yeah, I do too. Under this category also, you talk about pain. Um, the place that hurts isn’t always the place that’s injured.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:48:59] Okay. So.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:59] And this has so many levels, right?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:49:01] Exactly. And I thought of it because the physical therapist actually told me that about my back pain, saying like, oh, it’s probably your hip flexor. And I’m like, but that’s not where it hurts, you know? And then I and but then I realized it’s it’s metaphorically true too. Like a friend of mine was, was going to buy a new apartment and I said, oh, whatever happened with that? And she said, oh, I decided not to do it. I thought I wanted outdoor space, but I realized I actually want a husband. So she was thinking like, oh, like, I really need outdoor space. That’s that’s what’s bothering me about my living situation. You know, I need I need a little bit of outdoor space. It’s like, yeah, that’s not really what’s hurting.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:42] Mhm. One of the others on this category, um, getting it wrong, the person who knows the most facts doesn’t always have the best judgment. When we were kids we would have called this the difference between book smarts and street smarts.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:49:55] Oh. Yeah. Exactly. Exactly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:59] And I think everyone has like, lived this somebody is encyclopedic about something. They’ve read every book. They have a PhD.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:50:05] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:06] And then there’s the question about like some practical application.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:50:09] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:10] And it’s almost like you’re trapped in, in whatever is like the Archive of Knowledge is there as a searchable resource. But it’s like the application. How do we use this to make a decision or to, to behave in a particular way.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:50:27] Yes.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:27] They’re not mutually shared just automatically. And sometimes even they’re mutually exclusive.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:50:32] Yeah. Yeah. And it can. And sometimes the person with the most facts can kind of talk the biggest game. And you always have to remember like but is this person have the best judgment.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:42] Right. You’re like they’re so smart. They know so much more than me about this thing.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:50:47] Right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:47] And then when it comes down to actually utilizing that knowledge, it’s a completely different experience.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:50:53] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:53] Let’s spend the last few minutes I want to talk about um how do we start to think about doing this for ourselves. How do we create our own secrets of adulthood. Give me some guides here.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:51:02] So an aphorism is something that’s original to you. But I think for many people, a very useful secret of adulthood is a proverb that they’ve heard. Or, you know, something that they’ve learned from somebody else. So I think one good thing is just if something really strikes you deeply, write it down and keep track of it, because it can be very energizing to read these because you might think, oh, I’m never going to, you know, Dolly Parton said, find out who you are and do it on purpose. Wow. I’ll never forget that, you know, because I totally agree with that. It’s like you’re going to forget that in a week, right? If you don’t write that down. So it’s good to write it down. And then sometimes these are things that are just floating in the world that really resonate with us. Like when the student is ready, the teacher appears. Like, I didn’t say that, but you know, you might write that down. But then I think once you start looking for them or thinking in that way, you’ll start to, I imagine, discover that there are things that you think, or if you push yourself a little bit further, that you think about the nature of parenthood or how you think you should make decisions, or how do you stay resilient or whatever, something. Um, and then and write it down or as just happened here live on the podcast. If you’re reading something and you’re like, well, I would put a different spin on it, or I would say, I would say it differently, or I would say the opposite, like write that down, because again, it’s this it’s this way of surfacing our own values and our own observations in life that are incredibly valuable. One of the reasons I wanted to do this book is, you know, I just keep learning the same lessons over and over and over again. And so it’s just nice to write it down so you can be like, okay. Let me just remind myself one more time, you know, if I have to make a tough decision, choose the bigger life. Like, that’s just going to be a helpful thing. But I have to remember to do it. And so and you also might think about the people in your life, like a lot of times people will will just kind of say, well, my father always said blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. We might write that down and say like, okay, well, that’s in your head. Do you agree? Or maybe you don’t agree. Like if you’re not five minutes early, you’re five minutes late. And it’s like, do I agree with that? Do I think that’s right? That’s up to you, right? And that’s not an aphorism because that’s like a piece of folk wisdom, but it’s in your mind and it’s maybe guiding your thoughts. And so it’s useful to write it down and then react to it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:16] It’s so funny, as you shared that I was just I flashed back to New York City snark mode and I was like, if you’re five minutes early, you don’t have a life.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:53:24] Yeah, yeah,

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:25] because nobody’s five minutes early.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:53:26] Right, right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:27] You’re always 20 minutes late. That’s just the way it is.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:53:30] Yes. So again, it’s like you may agree. You may disagree, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:34] I mean, I was thinking also as you’re describing that I’m like the four big buckets and then sort of like the however many subcategories under each one of those four big buckets. Maybe that’s also really interesting frame for people to sort of say, okay, so let me use this as a guide. Let’s start with this one big bucket and then look at the different things that you’ve teed up and say, okay, so like what’s my thought under these different categories. What have I heard and what might graciously you provide a whole bunch of space at the end of the book for people to actually start to create their own as well?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:54:01] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:01] Before we send people off to start to explore these, are there any don’ts in terms of sort of like trying to create your own list?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:54:08] No, I think it’s I think there’s so many ways to do it the right way. I don’t think there is a wrong way to do it. And remember, like sometimes it’s just helpful to write it down and then you might decide you don’t agree with it. You know, it’s like just put a question mark after it. Because a lot of times sometimes when you really distill a conclusion down to one sentence. You’re like, wait a minute, do I even believe that? Is that do I? Is that true? Um, and that’s all part of the process. So I think, um, I think that there’s no one right way to do it. It’s whatever way it feels to you. And I think it’s also the kind of thing where it can be really fun to, to give it to other people in your life. We all trade these back and forth. I mean, I have things that somebody’s grandmother said to her. Oh, a friend of mine’s grandmother said, um, every happy couple should have an indoor game and an outdoor game. They play together. My husband and I don’t play an indoor game or an outdoor game. We’re still happily married, but I still think it’s an interesting idea. And I heard this from my friend’s grandmother, who I never met. You know what I mean? So part. But I wrote it down, so part of it is just the fun of like collecting these, handing these over to other people, especially if it comes from you or like somebody close to you. It is really it’s very satisfying. It’s very satisfying for me to give this to my daughters. I think people would find it very satisfying to share it with the people in their lives.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:55:25] We all want. We want to spare people the lessons that we’ve learned the hard way. Let them learn it by reading and not through tough experience also.

Jonathan Fields: [00:55:34] And it’s like if you come up with your own list of aphorisms and then you share it with other people, it’s also you’re sharing a window into how you think and see the world, which I think. Is really interesting.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:55:44] 1000%.

Jonathan Fields: [00:55:45] And again, they may agree or disagree.

Gretchen Rubin: [00:55:46] They will really reflect you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:55:48] Yeah. It’s so cool. It feels a good place for us to come full circle. As always, I wrap with the same question. You have answered this over the years, but it’s been a bit of time since I asked. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Gretchen Rubin: [00:56:03] Talking, reading and writing are the good life to me, and that’s my cubicle and my treehouse. It’s my way of contributing to the world and also taking from the world.

Jonathan Fields: [00:56:15] Thank you. Hey, if you love this episode, safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with James Clear about habits and identity. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help by Troy Young. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle Bliss for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app or on YouTube too. If you found this conversation interesting or valuable and inspiring, chances are you did because you’re still listening here. Do me a personal favor. A seven-second favor. Share it with just one person. I mean, if you want to share it with more, that’s awesome too. But just one person, even then, invite them to talk with you about what you’ve both discovered to reconnect and explore ideas that really matter. Because that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields, signing off for Good Life project.