Imagine waking up every morning feeling confident, capable, and ready to embrace whatever challenges the day may bring. No more second-guessing yourself or spiraling into overthinking – just an unwavering belief in your ability to handle life’s twists and turns with grace.

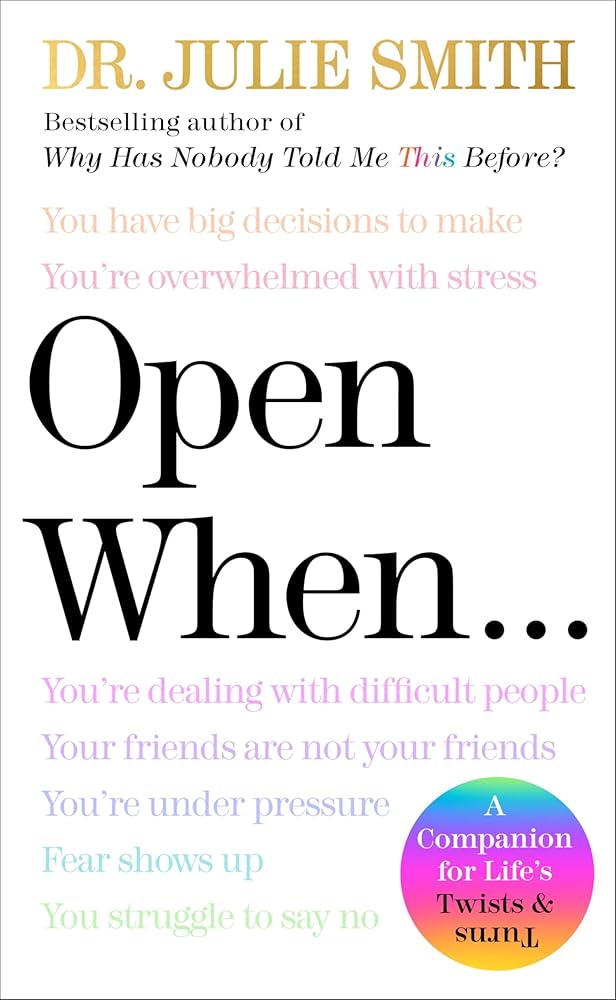

If this vision resonates with you, then you won’t want to miss my enlightening conversation with Dr. Julie Smith, clinical psychologist and author of the transformative book “Open When: A Companion for Life’s Twists & Turns.”

During our chat, Dr. Julie shares invaluable insights into quieting that persistent inner critic that so often holds us back. You’ll discover practical strategies for cultivating self-compassion, nurturing a growth mindset, and viewing failures not as indictments of your worth but as opportunities for learning and growth.

Whether you’re grappling with decision paralysis, crippling self-doubt, or a tendency to obsessively ruminate, Dr. Julie’s wisdom will empower you to break free from these mental prisons. Her approach blends profound empathy with actionable steps, ensuring you walk away equipped to transform self-criticism into self-kindness.

You can find Julie at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Cyndie Spiegel about experiencing small moments of joy.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Julie Smith: [00:00:00] Failure isn’t something you become. It’s an experience you move through.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:04] Doctor Julie Smith is a clinical psychologist, bestselling author, and mental health educator with an audience of over 7 million people. She’s become the go to resource for common sense mental health. Her latest book, Open Win, is a must have companion to help navigate everything from self-doubt and overthinking to confidence and overwhelm.

Julie Smith: [00:00:23] My innate drive is to protect my child.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:27] Every parent wants their kid to be safe.

Julie Smith: [00:00:29] It makes sense that I had thoughts like that at that time. I sat up with her in the night and just sort of looking at her in amazement and thinking.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:38] We have this just abject fear of choosing wrong.

Julie Smith: [00:00:43] How can we build confidence and have this kind of sense of confidence being a goal or a destination that you can arrive at? And and I always kind of say to people. I was always known as the the quiet one or the. And I think that was probably a symptom of being fairly shy introvert as well, which is, you know, different, but sort of a part of that. And I always had this sort of fascination with people and I never really sort of I only get that now. And I look back on, you know, I was a ferocious reader as a child. So I would just read lots of, you know, fiction and, and I never read any sort of fantasy or science fiction or anything like that. It was all you know about other kids in kind of family life. It was all kind of normal life stuff. And, and so I had that sort of fascination with people from a young age, I think, and how humans worked and how we were supposed to live and how relationships worked. And maybe that was related to that sort of shyness early on, I guess. And I would observe. So I would just watch, you know, when you’re shy and you’re not in the center of things, you know, being the heart and soul of the party. You watch and you learn and you absorb things. So yeah, I think it was definitely a part of the development of that sort of fascination with and, you know, not knowing at that point that psychology was even a word or a subject and sort of found myself in that world and equally fascinated by it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:21] So, yeah, it’s interesting, right? I think so I’ll raise my hand as a fellow, quieter person. And it really is such an interesting it’s almost like a trait of being on the quieter side that you have so much more space to observe what’s going on around you. That doesn’t mean you always do. I feel like oftentimes like you end up in your head rather than externally focused. But if you start to look out into the world, that’s like you just start to see things that maybe others miss, that maybe give you a different, more nuanced understanding of how people meander in and out of relationships and interactions. Years ago, I actually had the opportunity to sit down with Richard Branson’s mom, Eve, and we took a trip back in time, and she was sharing a story about how, in her mind, it wasn’t okay to be that child, you know, to be the shy kid and, like, part of your job if you were in a room, was to make other people feel comfortable. So she was telling a story about how, like, when Richard was, I don’t know, 5 or 6 years old, she drove him out to the countryside, basically booted him out of the car and made him find his way home, knowing that he would have to approach other people and ask them, you know, for directions. Um, and this was like training for her. He never actually made it home that night, by the way.

Julie Smith: [00:03:31] No, really.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:32] A couple of hours later, they started freaking out and they started getting they got back in the car. They were driving around. They finally found him, like eating dinner, you know, like at a neighbor’s table. He just like, you know, he found a place where he felt comfortable. He got invited in and just was enjoying himself. So kind of it didn’t. The lesson didn’t end entirely the way she thought it would.

Julie Smith: [00:03:51] I think I probably do a slightly less risky version of that where whenever we’re in like a local cafe or a shop or something like that. We’ll get the children to go and pay for something, but we’ll wait back and just let them kind of feel like they’re doing that on their own. So you’re close enough to pick up any problems. But they, you know, they get that real taste of having to make a conversation with an adult. And my daughter has done that from a really young age. And so, yeah, any time that she sort of was fearless in that kind of way, and my husband was like, yeah, go on, let her do it, that’s fine. And and now she, you know, she can, at 12 years old, hold a really good conversation with adults and is generally unfazed by it. It’s brilliant.

Jonathan Fields: [00:04:32] Yeah. That’s amazing to see that. I’m curious what it’s like for you, though, because I feel like for a lot of parents, you know, our we have this vicarious anxiety when we like, we want our kids to go out there and be brave and be vulnerable and do these things that we kind of know inside is really going to help them. But at the same time, you know, like they have their own potential hesitance or anxiety around it, but then we’re anxious on their behalf. So like, we feel like we need to step in and fix it or not do that or just do it for them. Not because they’re not necessarily ready for it, but maybe because we’re not.

Julie Smith: [00:05:05] Yeah. And, you know, I remember as you were talking and I sort of had these little kind of flashback moments of I first of all, being pregnant and feeling like my child is never going to be more safe than they are now. You know, they’re inside me, they’re protected from the outside world. And I can, you know, relatively keep control of this. And then this moment when my first child was born, kind of sat up with her in the night and just sort of looking at her in amazement and thinking, I don’t want you to ever feel pain. I don’t want you to ever feel alone or feel distressed, or be in physical pain or emotional pain and just not wanting any of those negative things for her. And that’s I guess that’s, you know, partly a biological thing and also a psychological thing being the mother of the child that it was, you know, my my innate, um, drive is to protect my child right when they’re born. So it makes sense that I had thoughts like that at that time. But you also kind of recognize on the other side that actually all of those things are a part of learning.

Julie Smith: [00:06:11] And you don’t build strength or wisdom or knowledge or any of those things from just sitting in a room and talking about them or thinking about them. You have to live. And, you know, we learn all those things through action and through trying things out and learning from when things go well and when things don’t go well. And I think that’s key in some ways. Some of the people that I’ve worked with in therapy before had never failed. They’d never had, you know, terrible things happen that they had to survive. And their confidence in their ability to cope with what might be up ahead was really low. And there’s something about, you know, obviously you wouldn’t wish negative things on anyone, but when certain things, certain challenges come along, even though they we might look back on them and say, you know, that’s a that was a really difficult time. Inevitably they leave us with this sort of unspoken or unwritten new sense of knowledge that we can cope with tough times and we can get through certain stuff and survive it. It’s a sort of inner strength, I guess.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:22] Yeah, I mean, that makes so much sense to me. You know, I think every parent wants their kid to be safe, you know? But I think what you’re describing sounds like it’s a fine line between wanting them to be safe and keeping the world small, and also not allowing them to blossom into the human beings that they could be, and move into the world with confidence and and all those different things. You know, when you’re describing that also, I feel like, um, there’s this opportunity where as a parent, you can watch your kid take risks when the stakes are low, and if they do stumble, that you can be there to help them process. And I often wonder, you know, rather than trying to protect them from everything, as long as they’re with you, as long as you have the ability to protect them from like, what if we just let them stumble as much as humanly possible when the stakes are low and we can help them so that by the time they go out into the world and we’re not there as much, that they’re just much better equipped to handle it.

Julie Smith: [00:08:20] Yeah, I think so. And I think in that sense, the best protection for kids is teaching them how to protect themselves in the future. So for example, my my daughter started playing football. So sort of English soccer to you guys. And she was new to it. And so there were other sort of girls in the squad that had more experience, and she wasn’t getting picked for matches and things like that. And so she was coming to me feeling upset about that and feeling like she wasn’t very good at it. And and the natural urge, as a mother is to make that go away. And I knew that a conversation with the coach might have changed some of that, but I didn’t want to do that. So I had to sit with her in her disappointment and problem solve with her. Okay, how are we going to how are we going to do that? You know, how do you get picked for a team? Well, you go off and you do the work and you practice and you get better until you’re so good they can’t ignore you. And and that’s what we did.

Julie Smith: [00:09:24] We joined another. We kept going with that, but we joined another kind of training program thing on a different day. And she did that for a year and, and built up some really good skills. And then lo and behold, she was getting more game time. And she was, you know, a sort of valued member of the squad. And, and so while that was, you know, painful for both of us in that she had to go through this period of feeling like she wasn’t really good enough for it. Actually, now she has a template for okay, when you get into that situation and you’re not as good as you would like to be in a, you know, a particular skill or, you know, ability of something, then you put the work in, you put the reps in, you think outside the box, you go out there, you find another way to build your skills up. And and then you come back and you try again, rather than having somebody come and fix it for you or, you know, force people into making, you know, including you when you’re perhaps not there yet.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:19] Yeah. I mean, that makes so much sense. And it really it also speaks to this word that you hear kicked around in the world of work these days, which is entitlement. There’s a bit of a divide, often sort of like between management leadership and the rising class of employees. And and I’ve heard this lament from both sides, you know, like I’m showing up. I’m like, I’ve been here for 18 months. I’ve been here for two years. Like it’s time for the raise. It’s time for the promotion. Like, this is like I do my time. I get the thing. And then from like leaders saying it actually has nothing to do with quote, time served like this is all about like how you’re showing up. Are you doing the work? Are you increasing your level of value and competence and contribution? And there’s a disconnect there. And what you’re like, what you’re offering is a way to bridge that gap.

Julie Smith: [00:11:06] Mhm. Yeah. And it’s interesting that we never get taught that in school do we. We kind of um get this impression that it is about time and that a certain age you’ll be promoted to a certain level and, and then, you know, a certain age you’ll have the house and the car or the child or the, you know, that there’s this sense of these things just happen. And there’s a certain maturity that comes with the experience of realizing, oh, actually, these things aren’t a given. I’ve got to put some work in. And maybe that’s a natural part of maturing, but maybe it would be easier for everyone, you know, employers and employees, if people were kind of taught this sort of sense at school, this sort of dealing with people that you’re working for and how to have those conversations and what you should be offering in return for a payment. Or you know what, the kind of a decent set of values are around an employment contract, and what to kind of expect of yourself and into and to expect of other people as well.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:01] Yeah, that makes so much sense to me. One of my mantras, just for life in general is no promises made. You know, that applies to another minute. That applies to like some benefit that you would really love to have. I think if we walk through life that way and just assume, okay, so this is all about the way that we show up. You know, it gives us, you know, both a sense of responsibility but also agency, you know, because it tells us we can actually affect the outcome. It’s not just a matter of waiting around or sitting it out or waiting it out.

Julie Smith: [00:12:29] Yeah. And I think agency is the key, isn’t it? And, you know, when I was talking about my daughter, in some ways that was probably the lesson for her was, was the sense of agency that when it’s not going your way, you get back on the front foot and you do something. You take some sort of action that can influence the situation, but in a positive way, rather than sort of complaining or looking to someone else to fix it for you or that kind of thing. And all of those experiences from a young age, I think, create that sense of agency, right? I remember when I got to university the first time as an undergraduate, I felt really lucky to be. That was the first person in my family to go to university. My mum’s entire wages were going towards keeping me there. And, you know, I knew that I wanted to make them proud for that. You know, I was grateful for their sacrifices. And and I’d also been in various different employments since I was 13. I think I took a, you know, a paper round, and I worked at an electrical cafe and shops in town and all these things, and I sort of had experience of having to go and earn some money if I wanted anything extra special. And when I got to university, there were other kids there who were much more privileged than myself and had sort of family life where they hadn’t had to necessarily work for things that they wanted.

Julie Smith: [00:13:54] Which sounds great. It sounds like a great upbringing and a great life. But when they got to university, those people were really struggled, really struggled, and some of them dropped out because they couldn’t manage their time and they couldn’t be disciplined and get to lectures or they couldn’t do the work, or they couldn’t budget, because even though they had the biggest pile of money in the account than than others, they had never had to learn how to budget or, you know, never had were never allowed to go to zero and experience that and going without. And so, you know. Well, when you know, if me and these, you know, other kids had compared childhoods, you might think that mine had in some way been worse. But in fact, I felt like I was much more equipped for young adulthood than I perhaps would have been if I’d have had everything I wanted. So even those sort of difficult things where you want to give your kids everything and, you know, make them happy in the moment. It’s not always, you know, there’s a lot to be said for delayed gratification.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:54] So true. Not easy to actually do in the moment, but deep down, knowing like, you know, the end is going to justify the means to a certain extent. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. I’ve been touching in different ways, actually, on some of the topics from your new book, Open Win. I love the structure of this, by the way, rather than this being a book where you kind of read it end to end, it’s like, now let me actually share a whole bunch of topics that are so common to so many of us. We just experience them in so many different parts of life. So you can kind of flip open. I mean, literally the title of the book is like basically open this. When this happens, you’re in this situation. I’d love to drop into some of those with you. And I think, you know, just riffing off of what we were talking about, that moment where kids show up or when we show up in a situation where we feel like in the moment we’re being tasked with doing something or showing up in a certain way or performing, and we just don’t feel confident at all. This is one of the things you write about, like there’s a sense of self-doubt that so many of us have. Take me into this experience a bit like how it often shows up and why.

Julie Smith: [00:15:55] Yeah. So I think confidence is often people often ask me, you know, how can we build confidence and have this kind of sense of confidence being a goal or a destination that you can arrive at? And I always kind of say to people, it’s not something you should aim for. It’s always a byproduct of a life spent being willing to be the beginner at something, being willing to be vulnerable, being willing to repeat that, you know, go into that space and stay there for as long as possible with the mindset of, I’m willing to not be perfect at this because I know I’m learning. And often confidence can be situation specific. A lot of the time I think there is some. There is a certain confidence in oneself that is kind of universal to a degree and that will you will carry with you in certain situations. But a lot of it is situation specific, right? So, you know, if I went with you to your workplace that you go to every day and or the things you do every day, I would probably feel out of my depth and not confident. And yet if I brought you to, you know, a mental health hospital or my clinic, then I would feel confident and maybe you wouldn’t.

Julie Smith: [00:17:05] And that’s purely about the experience, the time spent there, the training to deal with the different situations and all of those things are stuff you can learn and stuff you can build on over time. And I think the recognition that wherever you want to go, whatever you want to master and become more confident at, there is a path to that. It goes back to the agency thing, doesn’t it, that there is a way to it that, you know, it’s the fixed mindset, growth mindset stuff. If you think that how you are now and your strengths and weaknesses are fixed for life, then. Then you’re probably not going to do the work necessary to build your confidence. But if you’re willing to go there and you’re willing to begin to kind of learn and practice and get it wrong and scoop yourself up when you do fail, then over time, when you suddenly sort of you’ve put some work in and you look up a bit and you think, oh, I’m so much more confident than I was. There are still areas I want to work on, but it feels fundamentally different to day one on day 200.

Jonathan Fields: [00:18:10] No, that makes a lot of sense. And part of what you’re describing here is this notion of we can’t think our way into confidence. We kind of have to do our way into it.

Julie Smith: [00:18:17] Yeah. So our brains learn through evidence of action and experience. And, you know, I could sit in the therapy room with someone for hours on end, getting them to try and convince themselves that they are indeed confident. And it really just wouldn’t do anything. You know, it’s not going to move the dial, really. And what does move the dial is the stuff that happens between therapy sessions. So, you know, someone will. If I don’t know, let’s say someone has kind of social anxiety and they really want to become more confident in social situations. We create a hierarchy. So we list out all the different situations that cause anxiety in order of sort of graded in terms of how anxious does that situation make you. So, you know, at the very bottom it might be, um, starting conversation with the person in the local store down the road when I buy my food. And, you know, right at the top might be speaking to someone I don’t know at a busy wedding, you know, in a crowded room, all of those kind of. So there’s lots of different situations in between there. And each one might have, you know, a more intense, anxious reaction to it.

Julie Smith: [00:19:20] And what you would do in therapy is you don’t start with the worst one. The thing that’s really difficult, you start at the bottom and you start with a thing that feels like a challenge but feels doable. And and then when you do it, you go back to therapy and then you reflect on it and talk about it and talk about the experience. So or the sort of embedding the the small victories that you’re having and benefiting from when it doesn’t go well, because you’re turning that into a constructive learning experience. So you’ll reflect on when it doesn’t go well and what you could change to do next time. And so, you know, the sort of changes in your brain chemistry are happening when you’re having this experience and the work you do in therapy in between is a sort of embedding that and allowing you to be able to recall it and think it through in a coherent way. And so, yeah, we have to have the action in there. Otherwise. Yeah. When it’s sort of, I don’t know, trying to travel on a boat with no oars, you’re just you’re going to be floating around for ages.

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:18] Yeah. I’m curious where you land on this in this context also. So years ago, I remember being exposed to the work of a guy named Eric Reis in the world of entrepreneurship. He wrote a book called Lean Startup, which was this sort of like became the Bible for startups in that world for a long time. But there’s one line that stayed with me, and there was a lot that stayed, do actually. But this is one line like really like it feels relevant to this conversation. You know, he said, the thing that we’re trying to do here is we change the metric that we’re striving for, from success to learning. And when you do that, like when you’re talking about these iterations, like try the little thing and then the next thing and the next thing. If we enter that and say, okay, my goal here is not necessarily to succeed, but just to do the thing and learn something no matter what it is, whether like whether I’m embraced or whether I’m rebuffed, if my primary metric is just to learn something, kind of takes the pressure off. How does that land with you?

Julie Smith: [00:21:13] Yeah, yeah. And absolutely, in terms of when I talk to people about the difficult part of building confidence, in terms of being in that situation where you feel vulnerable. Certainly for me, the only way that, you know, I as the kind of the shy, introvert girl now doing things like live TV and big speaking events, the only way I’m willing to do that, or able to do that is that I’m willing to look at failures as and when they occur as a learning experience and as a necessary part of that learning experience. And that in the face of those failures, I’m not going to kick myself when I’m down. So anytime I make a mistake or if the worst happens, you know, if I fall over on stage and on live TV, I’m not going to use that as ammunition against myself. I’m going to I’m going to look after myself through it, and I’m going to speak to myself as if I was, you know, a coach who wanted the absolute best for me and to see me continue to achieve. So there are certain things you need to do to to help you get yourself back up rather than and, you know, seeing those missteps as a learning experience is key, because I think then you see it as outside of yourself. You see it as an experience you’ve had. So I see, you know, failure isn’t something you become. It’s an experience you move through. And. But when you attach it to yourself or you think that says something fundamental about who you are as a person, that’s dangerous ground, that’s going to be much harder to recover from, much harder to learn from even, because that will leave you in shame. And when you’re feeling shame, you can’t learn and move on. So yeah, you know, keeping a really sort of constructive relationship with failure is key.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:59] So you just brought up the s word shame, which I think is part of so, so much of why we shut down in so many different circumstances. We feel the sense. But I mean, you just made a really interesting statement also, which is when we’re in shame, we can’t learn to take me into that a bit more. I’m fascinated by that.

Julie Smith: [00:23:17] Well, it’s just so psychologically threatening when something that’s happened, and I think that’s the key, is when you think that whatever’s happened says something about your worth as a human being and, and your lovability or likeability or worthiness in whatever way. When you’re setting your estimation of yourself based on an outcome that you couldn’t really control fully, then you’re on really shaky ground because you’re the shame that you experience when you don’t feel enough for the people in your life. Um, is so threatening that you’re then in fight or flight mode, so you can’t. When you’re in fight or flight mode, you haven’t got time to think things through rationally. You just focus on feeling safe again. So inevitably then when we feel shame, we just start doing the things that that push that feeling away and help us to feel safe again. And inevitably, those, those behaviours aren’t the things that are helpful to us. You know, you kind of you don’t necessarily even notice what the feeling is or label it. You just notice you’re doing the thing that helps to numb it. You know, you’re I don’t know, you have a bad day at work and then you notice you haven’t gone home. You’re you’re in a bar drinking or, you know, something else that is potentially destructive. So but, you know, I think all of that can be helped by that clear separation between the mistake or the problem and me and my fundamental worth as a person.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:45] Yeah. No, that is so true. And also, I mean, it ties in really powerful. And this is another thing that it’s one of the chapters that you write about is this notion of like a fear of making a wrong choice, you know, like, so we’re like, we’re in this moment where we have to say yes or no. We have to allocate resources. We have to. And it’s funny because so many of us, I think, have this fear for the smallest things. You know, like, what am I going to order for dinner? But then the big things come where the stakes rise. And, you know, we have this just abject fear of choosing wrong. Take me into this a bit.

Julie Smith: [00:25:19] Yeah, and I think it can really I think it can really ramp up when we’re already struggling. So if we’re already under stress and we’re sort of reaching our capacity, then you kind of notice that seemingly small decisions that are normally not a problem start to feel like a problem, like the things like choosing dinner or, you know, deciding whether to go to that social event or not. And, and you can find yourself kind of ruminating over it. And sometimes that rumination can be a symptom of the fact that you’re already highly stressed or low in mood or both. And maybe you’ve got lots going on, which makes then decision making a real struggle. But I think sometimes when it’s a sort of a bigger decision, there can be that kind of sliding doors feeling of, you know, what? If I make the wrong decision and I regret it. And I think inherent in that idea is the sort of fallacy, really, that there is a right decision that will involve no cost, and it would just be payoffs, and it’s just not true. You know, if you, I don’t know, say you whether it’s a decision to have children or not have children. This sense that one of those will be the perfect decision, that will mean you’ll have the easiest and best and most fulfilling life just isn’t true. There are different paths.

Julie Smith: [00:26:42] Both of them might be brilliant in their own ways, and both of them will inevitably have a degree of cost to you and sacrifice. And so it’s not so much trying to weave through life, dodging anything that you might regret. It’s working out which regrets you’ll be able to live with, and which regret regrets you’ll be able to, or which costs that you’ll be able to carry, knowing that it’s still the right decision. So I know when I had children, for example. So before I had children, I was totally focused on my career in the NHS over here in the National Health Service and all the different things I wanted to do. And. And then when I had my daughter, it completely changed and shifted and and it didn’t it didn’t feel. And it still doesn’t feel like a cost to me that I made sacrifices in my career progression. You know, I didn’t go for the consultant job because I needed to be present for my daughter, and that’s exactly what I wanted, because my values had shifted. And so it no, even though it was potentially a sacrifice or would have been considered a sacrifice to my younger self, it now doesn’t feel that way because I’m clear on why I made that decision. And and I’m more than willing to, to pay that cost.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:08] Yeah, it’s it’s interesting because you bring in, you know, when you became a parent, you’re like, I think one of the things that we tend to struggle with is when maybe I’m just speaking for myself, but I would imagine it’s more general than that, is when you’re at a moment where you need to make a decision, the stakes are meaningful, but it’s not really your stakes. Maybe you’re making a decision for, you know, a young child who is not quite at a point where they can really make it themselves. Or maybe you have elderly or aging parents and you’re making decisions on their behalf, and you know that the decisions are going to be in really meaningful ways, affect either that young child’s future or, you know, your aging parents day to day life. And I wonder if sometimes like that becomes this added factor when we know that we have to make an important decision. And the decision is it’s not just going to affect us, it’s going to affect people who we care deeply about in ways that could be extremely good, but also extremely challenging. Do you see that come up?

Julie Smith: [00:29:12] Yeah. And, you know, even in my own life, when all this happened, you know, I originally left the NHS so that I could manage my work around the family. And I started this really small private practice from home that I could do in kind of school hours so that I could be present as a mom and still kind of keep my skills going and that kind of thing. And, and then when all of the videos I was putting on social media kind of took off and the book deal and then busy, you know, it was all kind of going wild. And I was really acutely aware at that time that I didn’t want it to affect the children. I made these decisions for our life so that I could be there and be present as a mom. And I was so I was so focused on it not affecting the kids. But I could also see the benefits to us as a family of doing this, and the sort of options that could create for us as a family. And so I was trying to do that and it not affect the kids. So I was essentially kind of not really sleeping that much. I was putting the children to bed, working until, you know, late into the night. And then I was getting up early to try and make videos and things, or right before they got up because we were in lockdown as well.

Julie Smith: [00:30:23] So they were at home. Um. And the person who paid the price for that was me in terms of, you know, lack of sleep doesn’t, you know, you can’t do that for too long before it has consequences. And, and so I think all of these things are a constant kind of balancing act, aren’t they? Of, um, you know, it wasn’t ideal to say no to all these wonderful opportunities that have been brilliant for our family, but it also didn’t feel right to say yes to all of them and not see my children. But it also wasn’t sustainable to sacrifice my own well-being in order to make sure everybody else was happy. And all the opportunity, you know, everyone offering opportunities was okay and my children were okay and I wasn’t. That didn’t feel like a good equation either. And so there’s always this kind of this toing and froing of this, you know, people imagine that balance is this perfect sweet spot where everyone’s got enough of you and you’ve got enough of you, and it’s just brilliant. And don’t shift from that. I think it’s more of a constant movement, a constant awareness of when you’re shifting too far in one direction, you readjust and, you know, balance the other way, and then you balance back and you come back and forth. And something that I talk about in both the books actually, is how important those simple values exercises are to me.

Julie Smith: [00:31:46] There’s something from therapy that I personally do, I don’t know, like every few months maybe, or if I’m just feeling a bit out of sorts or kind of, you know, overstretched or like, I’m not kind of living in the way that I want to. I’ll sit down and you just, you know, pen and paper. You just kind of jot out the different areas of your life. So I might put, you know, parenting, marriage, friends and social family, health, kind of learning, creativity, career, all of those things. And in each box, I just put a few words about what matters most to me in that part of my life. So not what I want to happen to me, but the kind of person I want to be and how I want to show up there in good times and bad. And then I kind of rate them. So I’ll give it a rating out of ten. In terms of, you know, it’s fairly kind of crude rating how important it is to me. So zero. Not at all. Ten is the most important thing. And then I’ll do another rating. But this time is how much. In the last couple of weeks I feel I’m living in line with those values, and all it does is it just kind of shines a light on the areas that I’ve shifted away from in that balance. And so if you’ve got a rating for an area of your life, let’s say health, and it’s ten out of ten important to you, but you notice you’ve put a two out of ten in terms of living in line with your values around that.

Julie Smith: [00:33:06] Then that’s just an indication of, hey, come over here. We’re a bit neglected over here. And so and it’s okay to you can’t have top scores on all of them all the time. And that’s okay. You know, it’s not a source of self-criticism. Criticism. It’s just an indication of when you nudge the balance and because inevitably life does pull you away, right? Sometimes there are big things going on, like with the, you know, the coming out of the book. For example, recently I’ve been doing lots of, you know, going up to London or doing podcasts and things like we’re recording this now. And so I had to drop the children over to my husband’s office, and they’re going to go off, and he’s going to take them to one of their classes. And, and I would normally be doing that. But that’s okay, because tomorrow I’ll pick them up from school and we’ll, you know, do stuff. So it’s that constant just adjustment, that rebalance of, yeah, I’m still looking after the things that matter most to me, and I’m fully aware of what those things are. But sometimes work will get a lot of me, and sometimes the children will and sometimes other things will.

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:08] Yeah, I love the way that you bring values into the exploration, and also the way that you bring a sense of self-forgiveness into the conversation as well and say like, you know what? I got to actually acknowledge and forgive my humanity, and the fact that I’m not living in this sort of like isolated, perfect world with perfect conditions of living a real life in the real world. And things are going to happen. I’m going to fall apart. The world is going to change. Things will come up and we’ll be right back. After a word from our sponsors. This is one of the other topics you write about this notion of self-criticism, and we can get so in our heads, like, you know, just kind of beating ourselves up and saying, you know, like I made this decision or I wanted this thing to happen in a particular way. I was a part of the way that unfolded, and it unfolded in a way that I absolutely didn’t want and hoped wouldn’t happen. And then, you know, rather than saying, okay, so it is what it is like, how do I actually what can I learn from it? And then how can I move forward. And this is a way to improve or fix this. So often, you know, we get just stuck in our head in this spin cycle of self-criticism, which can be so defeating. Yet it’s such a I mean, I would imagine this is something that you’ve seen in clinical practice over and over.

Julie Smith: [00:35:22] Yeah. And it’s something that people want to hold on to as well. You know, people a lot of people believe that it’s the source of their drive and their success because, you know, when things aren’t going so well, they are hard on themselves. And that’s what, you know, gives them the kind of kick to to try again or work harder and that kind of thing. And that’s all fair and well, but it also kind of assumes that you can only achieve from a place of threat, you know, from that kind of threat mindset of not going to be good enough. And, you know, I again, it’s the same stuff that you’re coming from, but you can have a sense of drive from a place of worthiness, but also wanting to, you know, discover your potential and discover your limits and do positive things for the world as much as you can. And that’s a much more pleasant place to come from in terms of drive and without the sacrifice of poor mental health. And because inevitably, you know, I remember one of the things that we used to kind of talk about in therapy was this idea of someone who is relentlessly self-critical. It’s almost the equivalent to, okay, you know, imagine if I was going to lock you in a room for a year and you weren’t going to come out of that room for the entire year. And I’m going to put in that room with you the worst bully that you can remember from school. And and they’re just going to be that bully to you for the whole year, 20, you know, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Julie Smith: [00:36:57] When you then come out of that room after one year, you know, you’re going to feel pretty terrible. You’re not going to come out with confidence, you’re not going to come out feeling happy and jolly, and you’re not going to come out with brilliant mental health. You’re going to suffer all the consequences of round the clock bullying. Whereas if you were in that room with your best friend or your favorite sports coach. You would come out with fundamentally different mental health, and feeling differently about yourself, and feeling raring to go with all the things that you’ve been dreaming about doing, without the self-doubt and the self-criticism that comes with it. And I would say that if for someone who’s relentlessly self-critical, it’s the equivalent to living in that room with the bully 24 over seven, because it’s in your head every minute that you’re awake, and that’s not without consequence. So if the way that you speak to yourself in your head sounds more like the bully than it does the best friend, it will be costing you and it will be affecting your mental health in a negative light. And so it’s this idea of, well, I think people have the misconception that if you’re going to be nice to yourself, that somehow kind of self-indulgent and that self-compassion is the same as indulgence, which, again, is not true. So, you know, compassion is actually often doing the really tough thing or taking the more difficult decision that has your best interests at heart. So it can be really difficult. So let’s say my son wakes up and he feels a bit tired, a bit groggy when he wakes up and he says, I don’t want to go to school today.

Julie Smith: [00:38:34] Indulgence might be me saying, okay, let’s not bother. You know, we’ll go in when you feel like it. That would be indulgence, whereas compassion would be, okay, I get that you’re tired. Getting to school on a regular basis is really important for your education. Here’s why. But we you know, we get up, we have some breakfast, we have a drink, and we, you know, see if you’re feeling better. And then we try anyway, even though you don’t feel like it. Let’s recognize that it’s important. So, you know, compassion is there for, you know, having his best interests at heart and encouraging him to do the thing that he doesn’t necessarily feel like doing because it’s going to help him in the long run and be better for his future. So it’s fundamentally different. And so, you know, you can you know, I don’t know have drive at work or you can get yourself to the gym or you can do these things that are difficult, um, from a place of compassion and caring for yourself, you know, treating yourself like you’re someone that you’re you have a duty to look after or if you’re, you know, taking on that role of a coach of an elite athlete, you know, you want them to achieve their, their, their capacity and their their potential. And so in order to do that, you can’t pull them down. You’ve got to lift them up, but you’ve also got to push them forward and not pull them back.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:53] I feel like so many of us are better at offering compassion to other people than we are to ourselves. You know, when you think about, okay, so how do I actually, um, be more compassionate in those moments to myself? Is there a question or a prompt or something that you would invite us to explore?

Julie Smith: [00:40:11] Yeah. You know, you hit the nail on the head there where, um, people that don’t have much self-compassion. It’s not that they are unable to feel compassion, it’s that most of it goes outwards towards other people that they care about. And so I always say that’s really good news, because it’s kind of just a process of redirecting some of that so that we get to share it around because we’re not asking someone to, you know, put themselves above everybody else in their life just to bring them up to that same level of priority so that they’re kind of treating themselves with the same care and respect they treat everybody else. So a really great exercise that, um, a lot of people have found really helpful is this process of thinking of someone that you love or care for unconditionally. And that was often a child in the person’s life, whether it’s their own or, you know, a niece or nephew or something like that. And you spend time kind of with that image in your mind and feeling what you feel towards them. And when you do that, you’re engaging with that feeling of compassion, and often you kind of then imagine that, okay, let’s say that person, that child or adult that you feel such compassion towards is in the situation that you’re in now and dealing with that problem.

Julie Smith: [00:41:27] What would you want them to have the strength to do? What would you want them to say to themselves? And what would you want them to do to work their way through it? And often that then just gives you this kind of idea of what would self-compassion really look like? Because inevitably you want that person to do what is best for them and what has their best interests at heart. And so it kind of creates this idea of, oh, okay. Yeah, I’d want them to, I don’t know, stand up for themselves or, or find a way to, you know, pull themselves out of bed and, and get to that exam even though they feel nervous or and not not be too hard on themselves when it went wrong or, you know, all of those things that we seem to be able to find that for other people so easily in the moment, for ourselves, it’s really difficult. So there’s lots of different exercises like that where you you engage with the compassion, you kind of push it where it moves. So you find that compassion that you can feel and then you redirect it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:26] Now, I love that it’s funny as you’re describing that what came to me also is what’s often classically known as the metta meditation or loving kindness meditation, which is, you know, it’s repeating generally like a handful of simple phrases, you know, like things like May. May you be safe, may be healthy, may be happy, may you live with ease. But classically and you cycle through different people. And that meditation takes only a few minutes. And the first person that you’re often taught to start with is yourself. You know, you start by saying, May I be safe? May I be healthy, may I be happy, may I live with ease. And then you go to a person who you really care about unconditionally, and then you go to a person who is a stranger, and then you go to a person that you struggle with, and then you go to all beings. But it’s interesting that what you’re offering is sort of like this interesting reframe. And saying that first reframe for a lot of people may not be super accessible, you know, like May I. So what if you actually started with that person? That’s the next ring out where it’s like, no, I can find it for this person and then work back into it. It’s like this interesting shift in that.

Julie Smith: [00:43:29] Yeah, I think that’s exactly right. I think you have to start where it’s easiest to access it, and then it’s a shifting rather than a trying to generate something that you’re not used to feeling. So that can be really helpful.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:41] Yeah, I love that. I feel like this also leads into another topic that you dive into, which is the notion of overthinking. You described self-criticism as something that sometimes people like to hold on to because they feel there’s value in it. Overthinking is this interesting, very wide ranging phenomenon. So many people I know really get stuck in this. Weirdly, I’m somebody who doesn’t spend a lot of time in overthinking, and I’m probably the outlier among most people that I know and that I’ve learned and I’ve had conversations with friends and with colleagues and and some of them have told me, they said, I like I know it’s hurting me. I know it’s a really uncomfortable experience, just emotionally for me, but I believe there’s value in it. I don’t want to let it go, because if I keep spinning this thought in my head, it’s going to at some point, it’s going to get me to a solution or to the big idea or to the thing. So I’ll just suffer with it. Do you see that as a common phenomenon, also with overthinking?

Julie Smith: [00:44:39] Yeah, I think that that is the sort of the I want to know what the word is, whether it’s a sort of almost a mirage, isn’t it, of or the illusion of worry and overthinking. Is that it? And why it’s so addictive in some ways, is that it gives us the impression that we’re solving the problem, and often what we’re doing, rather than solve it, is to, you know, cause worry by definition, is sort of unconstructive. And so what we tend to be doing really is rather than problem solving it in a constructive way, we’re actually just playing out that worst case scenario or a variety of worst case scenario thoughts over and over again. What if this happens? Or what if that happens? And so often what we can do in a kind of therapeutic situation is allow for this and not kind of trying to squash it or pretend those thoughts aren’t there. We’re saying, okay, well, what if then? So what if that worst case scenario, what do we do either to prevent that or what do we do when we if we get there and that happens and try to create that sense of agency so you can turn those particular situations into action. So you’re doing something about it and you’re getting off that sort of back foot feeling of rabbit in headlights. Things are happening or can be happening to me and I’ve got no control over it to okay, well, what are we going to do then? Let’s put something in place and either try to prevent it or prepare for when it’s going to happen, so that we deal with it in a way that makes us proud.

Julie Smith: [00:46:05] And I think sometimes that’s what worry in itself, or overthinking neglects, is the agency and the action that comes with it, because it’s all fair and well to think about worst case scenarios. And it’s actually a real benefit. It’s not something that’s wrong with our brain. It’s really helped. It’s kept us alive all this time, but it kept us alive when we were able to turn that into action, to keep ourselves safe. And and if it’s worrying about something that, that we don’t need to worry about. So there’s nothing we can do to keep ourselves safe. Or, you know, if I’m sat here worrying about one day I might get some illness that I don’t know what causes it or how to prevent it. Or, and I could sit here for the next ten years and worry about it with the possibility that it might happen then. There’s not really many ways to be constructive about that, unless there’s some sort of health behavior you could do right. And that’s the stuff to be, to learn to let go with mindfulness and thought diffusion, that kind of thing. But if it’s something that, you know, if it’s, you know, I’ve got a speaking event next week and I feel super anxious about it and I’m imagining worst case scenarios. Then there’s something I can do about that. Often that worry will be because I’m unprepared, and I need to put some things in place to prevent those worst case scenarios from happening. And, you know, that’s really easy to kind of access that sense of agency over.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:26] Yeah. No, that makes so much sense. You know, I feel like so many of the things that we’ve been talking about, it’s like action is the answer, not just random action, like some sort of like intentional, like thoughtful action. Because action can also probably deepen the harm or deepen the painful emotion. And yet, like if we just stay in our head, then it’s like there’s no resolution. It feels like a place for us to come full circle in our conversation as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Julie Smith: [00:47:57] I guess the first thought comes to mind is the value stuff that that I was thinking about before. To me, a good life is really simple, being the best that I can be for my family and the people that I know and care about and the wider community, and trying to be a force for good within that. And I guess even in the stuff, you know, even in the work that I do, I’m reaching beyond my own community to, you know, strangers on the internet. I can’t change the whole world, but I can make my small corner of the internet a positive one. So it’s always just trying to make sure that everything that I put out there is with positive intent to do some good, and inherent in that is looking after myself to ensure that I can do that for as long as possible.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:56] Thank you. And before you leave, if you loved this episode safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Cyndie Spiegel about experiencing small moments of joy. You’ll find a link to that episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help By Troy Young. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle Bliss for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project. in your favorite listening app or on YouTube too. If you found this conversation interesting or valuable and inspiring, chances are you did because you’re still listening here. Do me a personal favor. A seven-second favor. Share it with just one person. And if you want to share it with more, that’s awesome too. But just one person even then, invite them to talk with you about what you’ve both discovered to reconnect and explore ideas that really matter. Because that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.