Have you ever struggled to speak up in a tense moment? Felt too intimidated to share your perspective when it really mattered? Maybe you dread bringing up touchy topics, unsure of how to speak your truth while preserving relationships. If so, you’re not alone. We’ve all faced those awkward moments where communication breaks down right, and you find yourself unable to say what you need to say, to feel seen and heard, especially when connection matters most.

Have you ever struggled to speak up in a tense moment? Felt too intimidated to share your perspective when it really mattered? Maybe you dread bringing up touchy topics, unsure of how to speak your truth while preserving relationships. If so, you’re not alone. We’ve all faced those awkward moments where communication breaks down right, and you find yourself unable to say what you need to say, to feel seen and heard, especially when connection matters most.

My guest today, Sam Horn, has devoted her career to helping people bridge divides through better communication. Drawing on her experience as a kid with emotionally distant parents, where things didn’t get talked about, but rather tucked away or, at best, talked around, she realized early on the critical importance of open, compassionate communication. And, she’s devoted her career to helping others share, listen and connect on a deeper level as the founder of the Intrigue Agency and Tongue Fu training programs. She’s truly an expert on transforming hard conversations into meaningful connections. And doing it in a way that centers dignity and ease.

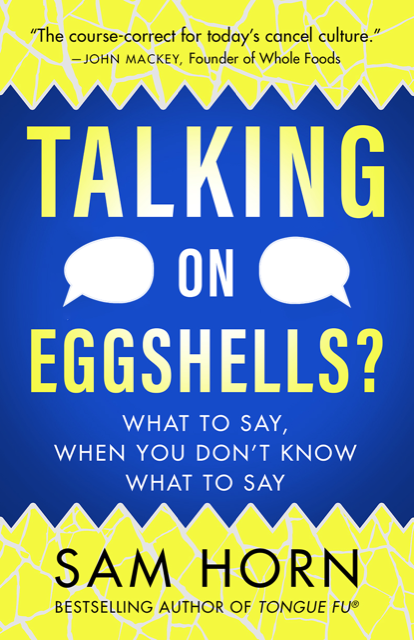

In our discussion, Sam shares her unique perspective on transforming conflicts or what she calls “talking on eggshells” into clarifying, satisfying conversations. We explore the essential skills of awareness, active listening, and empathy needed to shift from reactive to proactive in any challenging interaction. She also dives into key strategies from her newest book, Talking on Eggshells: Soft Skills for Hard Conversations.

If you’ve ever felt too intimidated to speak up, this episode will give you hope. Join me in learning how to find your voice, even on eggshells – starting from within yourself and radiating outward.

You can find Sam at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Zoe Chance about the language of influence.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- My New Book Sparked

- My New Podcast SPARKED. To submit your “moment & question” for consideration to be on the show go to sparketype.com/submit.

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Carl Studna

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Sam Horn (00:00:00) – Our dreams will go down the drain. If we cannot figure out how in 60s to get it across in a way that people are curious.

Jonathan Fields (00:00:10) – So have you ever struggled to speak up in a tense moment? Felt too intimidated to share your perspective when it really mattered? Maybe you dreaded bringing up touchy topics, unsure how to speak your truth while preserving relationships. Or maybe you’re just in a conversation where you have an idea that is so deep to your core, that is so passion filled for you, but you just can’t figure out how to get it out in a way that feels truly compelling. So if so, you’re not alone. We have all faced those awkward moments where communication just kind of breaks down. Then you find yourself unable to say what you need to say, to feel seen and heard, especially when connection matters most. So my guest today, Sam Horn, has devoted her career to helping people bridge divides through better communication, drawing on her experience as a kid with emotionally distant parents where things just didn’t get talked about, BUtrillionATHER tucked away or at best talked around.

Jonathan Fields (00:01:06) – She realized early on the critical importance of open, compassionate communication, and Sam has devoted her career and much of her adult life to helping others share and listen and connect on a deeper level. As the founder of the intrigue agency and food training programs, she’s truly an expert on transforming hard conversations into meaningful connections and doing it in a way that centers dignity and ease. In our discussion, Sam shares her really unique perspective on transforming conflicts, or what she calls talking on eggshells into clarifying, satisfying conversations. We explore the essential skills of awareness, active listening, and empathy needed to shift from reactive to proactive in any challenging interaction. And she also dives into many of the key strategies in her newest book, Talking on Eggshells Soft Skills for Hard Conversations. If you have ever felt too intimidated to speak up, or that you had something inside of you that just had to get out but didn’t know how. This episode will give you not just hope, but skills. Join me in learning how to find your voice, even on eggshells, starting from within yourself and radiating outward.

Jonathan Fields (00:02:20) – So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is a good life project. There are so many places to drop into. I think so many points of curiosity that I have about you, about your work, certainly about your most recent work talking on eggshells, because I think it is so of the moment and will dive deep into some of the ideas around that. You have largely developed your adult professional life around, really diving into various aspects of communication, how human beings relate to or don’t relate to or share ideas or don’t share ideas struggle to actually find common ground. You really focus around the idea of how do we share succinctly and clearly and in a compelling way, and also receive in a generous and open and kind way. When I see somebody who’s so deep into this type of exploration for so long, my curiosity is always what’s underneath that, what’s underneath it, beyond the professional pursuit, beyond just the impact on a professional level, supporting yourself, doing something that’s genuinely interesting and engaging and valuable, like what’s driving underneath that? What is the underlying impulse that has led you to devote so much of your energy, your love, your life, to this exploration?

Sam Horn (00:03:43) – Well, I grew up in a Cold War and not that Cold War.

Sam Horn (00:03:47) – It’s my dad was very emotionally distant and my mom was emotionally wounded. And so, Jonathan, they didn’t talk. I remember we would go on drives and hours would pass by without them saying anything. And of course, I would say, oh, there’s a horse in the field, you know, there’s anything to try and get them talking together. Because I could not believe that people who were married together had so many years of unhealed wounds that they didn’t even know where to start. So they didn’t start. And so I really, at a young age, I think, became convinced that this ability to connect through communication was going to be my life work. And you’re right, it is the river that runs through my work, whether it’s tongue fu or whether it’s talking on eggshells or got your attention, is how instead of staying silent or suffering in silence, can we initiate a meaningful conversation where we truly connect with other people?

Jonathan Fields (00:04:46) – Yeah, I mean, it’s really interesting. I’ve done a fair amount of work studying belonging and lack of belonging, isolation.

Jonathan Fields (00:04:53) – And one of the things that I saw in the research was that being cast out affects people differently. For some people, it actually makes them want retribution, and for other people it actually makes them prosocial. It makes them really want to do everything, to make everyone happy and to be invited back in. As a kid growing up in that environment, it strikes me that you had choices to make about how you were going to step into this, or are you going to be proactive and see, like, can I play a healing and constructive role, or can I just really isolate myself from this experience to protect myself? Curious how you navigated that dance?

Sam Horn (00:05:30) – Well, it’s interesting because I think in my DNA is to be proactive. It’s, you know, I grew up on a ranch, and when things could go wrong, our dad would say, you know, you can bellyache or you can get busy. And so I think complaining, revenge, all of that is a waste of our time. And so I think why I chose instead to unpack it and think there’s got to be ways, right? There’s got to be specific steps that we can use to bring up a hard conversation.

Sam Horn (00:06:00) – There’s got to be something we can say when people aren’t listening. There’s got to be something we can do. So I think it is in my nature to figure things out.

Jonathan Fields (00:06:10) – When you’re in that place. Also, as an adult, we can have this conversation in a rational, reasoned way, hopefully intelligent. But when you’re a kid, a lot of times when you’re in the situation you described, there is a taking on of blame that happens. Like is the fact that we’re in this car ride for hours and my parents aren’t talking. Is that about me? I’m curious whether that was ever part of your narrative.

Sam Horn (00:06:35) – Interesting. Taking on blame for it. I don’t think I was responsible for it, and I don’t think that it was because they didn’t care about me or my sister or my brother. I grew up riding horses in this very small town, and we used to ride our horses to the library, and it was very interesting because our parents did not worry and they did not caution us.

Sam Horn (00:06:59) – You know, it’s like, get bucked off, figure it out, bridle breaks, figure it out. And so I honestly think that it became my automatic response to things is like instead of complaining or blaming or it’s my fault or something, I just really get right to it and see how I can get resourceful and figure it out. So I think if you talk with anyone who knows me, they would say, yeah, that’s kind of who she is and what she’s about.

Jonathan Fields (00:07:22) – I mean, it’s interesting also, as a lifelong entrepreneur, you learn pretty quickly that at some point you want to do a bit of a debrief. More post mortem. But when you’re in it, all that really matters is that you fix it.

Sam Horn (00:07:35) – It’s, you know, our cattle got out one time at 2 a.m. and so a neighbor called and said, hey, your cattle is out on the country road. And the blaming begin, right? You know, Dave said, well, you were the one who left the fence open.

Sam Horn (00:07:45) – It wasn’t my fault. You were the one who and dad said, hey, that’s not going to get the cattle back in the pasture. Let’s go ahead and get up. You know, find him, you know, fix the fence and then we’ll debrief this in the morning. So once again, in fact, it is the river that runs through my work is whether we don’t have confidence, whether we feel like we’re not being given the promotion we deserve or the love that we deserve, that we can spiral into all of this navel gazing as my folks would cause it. Or we can really say, all right, you know, I think you use the word agency right at the core of who we are. We believe we have agency, and that means that it serves no good purpose to throw our hands up and kvetch about and complain about it and run around in circles or to point fingers about it. It is really to figure out, what can I do? How can I take responsibility for making things better?

Jonathan Fields (00:08:40) – Yeah, let’s talk about the word agency and a world that you existed in for quite a number of years, a bad part of two decades.

Jonathan Fields (00:08:48) – And I guess you still exist in the world of writers and writing and authors and creating with the written word and the spoken word. But very specifically, you headed up in various roles this legendary event in the world of writing the Maori Writers Conference, which is sort of, you know, like this is the place that a lot of established writers go that agents, that publishers, but also a lot of aspiring writers. And it’s a place that they would go often hoping to have their five minutes, their ten minutes with the people who could potentially make or break their careers, at least in their minds. You had this really unique window on the dynamic that was happening over and over a year in, year out. And it seems like that experience was also really seminal in your desire to help people really understand how to share what it is. It’s not just in their heart, but what they want out in the world.

Sam Horn (00:09:42) – So let’s put this in context, right? Is that at that time, you’re an author.

Sam Horn (00:09:47) – Most authors went their entire life and never met an agent or an editor face to face. Right? They would send out these query letters and maybe get a standard rejection letter back. Their whole career they were isolated from the decision makers. So what we did really was unprecedented. It’s that we brought the top agents and editors. We brought the mountain to Muhammad. I mean, you could imagine you could pitch your screenplay to Ron Howard. You know, you could pitch your novel to the head of Simon and Schuster. And I will always remember the very first day of our pitch sessions. A woman came out with tears in her eyes and I went over. I said, are you okay? And she said, I just saw my dream go down the drain. I said, what happened? She said, I put my 300 page manuscript down on the table. The editor took one look at it, said, I don’t have time to read all that. Tell me in 60s what it’s about and why someone would want to read it.

Sam Horn (00:10:42) – And she said, my mind went blank, you know, she said, it’s taken me three years to write it. I thought it was his job to figure out how to sell it. And my epiphany was, is that our dreams will go down the drain if we cannot figure out how in 60s to get it across in a way that people are curious. I talked with Bob Loomis that night. He was senior VP of random House. I said, Bob, what’s going on? He said, Sam, we’ve seen thousands of proposals. We make up our mind in 60s whether or not something is commercially viable and whether we’re interested. And that next day, I stood in the back of the pitch room and I watched people from around the world. This was their golden moment right there, and I could predict who was getting a deal without hearing a word being said. Based on one thing, the decision makers eyebrows. Because see if the eyebrows are crunched up, like right now, anyone listening or watching think about what’s something they care about.

Sam Horn (00:11:38) – What something they want to win funding for. They want to get approval for greenlighted, and they’re explaining it. And now, if the decision makers eyebrows are crunched up, not good. It means they’re confused and confused. People don’t say yes. Now, if the decision makers eyebrows were unmoved, it meant they were unmoved. And if the eyebrows were up, it meant they were intrigued. Curious. So I think that our goal in communication is to take something complex that we care about and then get it across. In a way, those eyebrows go up.

Jonathan Fields (00:12:10) – It must have been so interesting to sort of run that experiment for you, like being able to scan the room and eventually key in on this single metric would let you know non-verbally what was actually happening in those conversations. And I wonder how many of us pay attention to that level of nonverbal communication. Also, I know so much. Of what you focused on is verbal. How are we actually communicating with our words? But also depending on the research that you look at, you know, a significant percentage of communication is nonverbal.

Jonathan Fields (00:12:41) – And I feel like often we are completely not tuned in to. We just miss so much of what goes on in a short interpersonal engagement.

Sam Horn (00:12:53) – You’re 100% right. In fact, Jeff Weiner, who was former CEO of LinkedIn, said this is the number one career gap right now in people in the workplace is this ability to look around, to look ahead, to read the signs, read the room, and then respond accordingly. Right. My first boyfriend was a rafter, so we would go down the Stanislaus River almost every weekend. We went down the Grand Canyon together, the salmon, and he gave me a great metaphor for just what you’re talking about, which is to have our head on swivel and instead of just, here’s what I want to say or here’s what I want to ask, or I’m going to tell him how I feel, that’s like having blinkers on, right? It’s being insensitive. It’s not even taking on board whether this person is receptive to it or resistant. So he says when he goes down the river, he is constantly looking around.

Sam Horn (00:13:43) – It’s like, wait a minute, he’s listening. That rapid is a lot louder than it normally is. I think I’m going to pull over and walk ahead and scout it right. It’s like, oh, I see the current is going to carry us into a canyon wall and flip us. I think I’ll pull over here. It’s like, oh, there’s an eddy. Easy to get into, hard to get out of. So he calls it it’s not being a boatman, it’s being a river guide. And I think what you’re talking about is whether we walk into a meeting or whether it’s a family meal is to be a river guide. Okay. Who’s not talking? Right. Something going on with him? Something happened at school today or at work. It’s like, who is like, nodding, but their their jaws clenched and I can tell you’re not really buying into it. And I think the more we have our head on a swivel and we’re looking ahead and anticipating the reactions, the more we can adapt what we say and do to increase the likelihood of things going right instead of wrong.

Jonathan Fields (00:14:39) – Yeah, that makes a lot of sense to me. And that also really brings us into one of the core ideas of your recent work, talking on eggshells. You know, so this is a book which is really focused on, I think, a feeling that so many of us have these days, which is you walk into a room, a conversation, and you just don’t know exactly what to say. You don’t get the social dynamic, the context, the sensitivities, and you want to do the right thing. You want to be perceived and received the right way. You’d like to share whatever the ideas that you have, and also be received nicely and be open to that in exchange. And yet in so many environments, we’re so concerned that that is not going to happen, or that we may do or say something that actually not only doesn’t land in the way that we want, but actually offends, or that we may end up on the other side of that, that we feel like we can’t actually show up in a meaningful way.

Jonathan Fields (00:15:29) – We can’t say the things you want to say. We can’t hear the things you want to hear. We can’t move through an experience the way we want to. And early in that conversation in the book, you address this thing that you describe as interpersonal situational awareness, which is really, I think, building on this idea of being the river guide that we’re talking about. Exactly.

Sam Horn (00:15:48) – And it’s really based on a quote from Desmond Tutu. Desmond Tutu said, we’ve got to stop pulling people out of the river. We’ve got to go upstream and find out where they’re falling in. And this is the type of preemptive thinking where we do before we go in and ask for a raise, we ask ourselves, are they in the mood to give us a raise? You know, before we pitch something that’s going to cost money, we think, why would they say no? Oh, well, they’re going to say we don’t have money in our budget for that. So guess what? The first words are out of our mouth.

Sam Horn (00:16:18) – You may be thinking not I know you’re thinking because that’s presumptuous, right? But you may be thinking we don’t have any money in our budget for this. You’re right. And that’s why I’ve identified. And once again, if we Desmond Tutu this if we think upstream that we are going to increase the likelihood that people are open to what we’re saying instead of right out of the bat, they’ve got their mental arms crossed and the answer’s no.

Jonathan Fields (00:16:46) – And a lot of this is really I mean, it comes down to awareness. You actually have this quote. There’s little we can change until we notice how failing to notice shapes our thoughts and our deeds. You know, and this is the fundamental skill of awareness, both internal awareness environmental awareness. And then interpersonal awareness is a skill that’s so fundamentally to just the human experience going well and yet so rarely taught. And I’m curious whether you have a take on what’s going on there.

Sam Horn (00:17:15) – Jonathan. It’s like not only is paying attention and noticing the key to interpersonal situational awareness, it’s the key to good life.

Sam Horn (00:17:24) – In fact, I know we both really appreciate Mary Oliver’s poetry. And she said instructions for life. Pay attention, be astonished. Tell about it. Right. And so I really think that noticing is that if we are not aware and appreciative of what’s going on around us, we are going through life with our head down and we’re missing most of it. And so not only I think is it a prerequisite for a good life, because when we’re noticing and appreciating, we’re in a state of gratitude, which is a good life, I really think it’s the key to being a good parent or a good partner or a good leader. And once again, it is. Instead of being consumed or absorbed in what we want, what we think, what we believe, it is this lovely balance of yes, focusing on that in tandem with what’s going on around us so that we can be this force for good.

Jonathan Fields (00:18:22) – Yeah, that makes a lot of sense to me. And I feel like it gets us closer to the truth and also gives us more of the ability to have that word again, agency, but in the context of a clearer understanding of what’s really happening, rather than an assumed understanding of what may or may not be happening, which often is anywhere from delusional to mildly off course.

Sam Horn (00:18:45) – You just brought up, I think what’s at the core of many conflicts is this assumption that they, you know, that they are not listening to me, they’re ignoring me, they’re not appreciating me. And it is that our anger is based on an assumption, right. That often is inaccurate. And so I think one of the core ideas of the book is how can we turn a conflict into a clarifying conversation? And that’s by asking instead of assuming, right. And there’s this lovely story about a friend’s granddaughter who got a job and she’s learning disabled. So she was very happy to get this job, and she really applied herself. And when her manager told her she was up for promotion, she was thrilled. The very next day, she told her that she was in danger of getting fired. Now, before Bethany would have spiraled into depression, she would have probably left in tears, maybe quit. Her therapist had given her six words, and she went back in the next day and she said, can you please help me understand? Right? Can you please help me understand how I was up for promotion and now I’m in danger of getting fired? And her manager told her about a situation where a customer complained and Bethany remembered the situation.

Sam Horn (00:20:01) – She explained what happened now that the manager knew what had really happened. She thanked her for enforcing their policy, gave her their promotion and look at the different ripple effects. Right? Conflict avoided. You know, this is so unfair down the rabbit hole of blame and outrage. Or could you please help me understand? And it led to an understanding we were on the same side instead of side against side.

Jonathan Fields (00:20:25) – Yeah. And it’s a great example of a lot of the different ideas that you talk about. I think so often we enter a conversation where there’s a perception of the potential for conflict, and immediately there’s something that happens inside of us that says, hey, I don’t want to be here, be I don’t want to engage in this and see, like, how could this possibly go right in your mind? What’s really happening here? Because at the root of all of these ideas around this new book, it’s really about it starts from our what I think would be, I don’t know whether it’s a nature or nurture reaction, but certainly an ingrained reaction by the time we’re adults to the potential for conflict.

Jonathan Fields (00:21:04) – What’s underneath that in your mind? Why do we recoil so much from these potential interactions that the way that you’ve just described, even just from 1 or 2 short examples, also hold the potential for resolution and mutuality? You know, it’s.

Sam Horn (00:21:19) – Ironic, isn’t it? We’re taught calculus. We’re not taught what to do when people complain, you know, we’re taught history. We’re not taught how to have a hard conversation. So as you said, it’s not only ingrained to be conflict averse or to be an accommodating or to be angry or something like that. It is a habit. It’s a default. It is our reaction when things go wrong. Well, Elvis said it best. He said when things go wrong, don’t go with them. When things go wrong, a lot of times. We go with them because we react, because we haven’t been taught any different. And that’s really hopefully what people learn in the books is like, there are things you can say that will help instead of hurt. In fact, I really think the quickest way to make complex ideas crystal clear is to put a vertical line down the center of a piece of paper, and on the left is like words to lose, and on the right is words to use.

Sam Horn (00:22:11) – So say someone accuses us of something that’s not true. Our first reaction is to deny it. How could you say that? That’s not true. You don’t care about your customers. I do too care about our customers. Look, we’re arguing with our customers about whether we care about our customers. So over on the right, we say these four words. What do you mean are they may say, well, I’ve called three times and left messages and I haven’t heard back all the real issue. So see, we can actually learn when someone says, you never listened to me, I do to listen to you argument rabbit hole back and forth. Well, what do you mean? Well, you’ve had your head and your phone for the last half hour. You’ve never even looked up that those four words shift us from being reactive to proactive. And as you said often they can learn to a win win outcome instead of this rabbit hole of anger and resentment and outrage.

Jonathan Fields (00:23:06) – Yeah, I mean, those four words are so powerful.

Jonathan Fields (00:23:09) – I wonder if often what comes out when we think about those four words is something which at least lands more as well. Show me the example, prove it. And I think it’s the same intention. And yet there’s a way to say to invite somebody to share more about why they’ve landed in the position they’ve landed in. But there’s also a way to to essentially want the same information, but have it come out and be received largely as an attack. And I wonder if, in your experience, you’ve seen that that happens more often than not.

Sam Horn (00:23:40) – Boy, you’re bringing up tone, right? Because look at same words. If I say, what do you mean, right? Oh look, an angry face, angry tone and those words. That’s not a question. That’s a that’s that’s an attack, isn’t it? And so this is there’s a saying be curious, not furious. Right. And so we really are asking with the belief we don’t understand what they mean. And only when we find out what’s behind it do we have the explanation or the situation.

Sam Horn (00:24:08) – And we can respond to that. In fact, I was speaking at a women’s leadership conference, and in the Q&A, a woman put her hand up and she said, Sam, why are women so catty to each other now? Jonathan, I’d heard that many times before and I thought, I’m going to Don Draper this because Don Draper said, if you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation. So sometimes we don’t ask, what do you mean? Or why do you say that? And we certainly don’t deny it, because if I said, I don’t think women are catty to each other, now I’m arguing and perhaps reinforcing her point. So instead you say, do you know what I found? Women are real champions of each other. So sometimes when people make an attack, instead of digging deep and finding out where they’re coming from so we can respond to what’s really happening instead of the accusation, sometimes we make a judgment call. You know what? I don’t want to go there. I’m going to change the conversation and go on record with what I do believe, instead of arguing about what I don’t.

Jonathan Fields (00:25:12) – Making that judgment call is not always the easiest thing, you know, because there are moments that I would imagine it makes sense to do that. It’s a redirection, and you’re trying to redirect it in a positive way and posit maybe even an alternative set of facts that allow somebody to think differently about it or frame it differently. But are there moments where you feel like, actually this is an issue which is so important and so charged, but also it really does need a direct response. It does need a direct, not attack, but it needs to be refuted in a meaningful way. Yes.

Sam Horn (00:25:49) – And so what are the criteria. Right. Where we can make informed judgment calls. Because in a way that’s it’s constant iteration, right, is when we’re dealing with people at work or online or at home, we’re constantly trying to make judgment calls in the moment. What can I do or say in this situation is going to help or hurt? So I think one of the criteria is if this is coming from someone and we’re in a relationship with them, it’s a child, it’s a parent, it’s a sibling or whatever.

Sam Horn (00:26:18) – And especially if they say something with a lot of emotional vehemence, it means it really matters to them. And if they matter to us, then, well, if they feel this way now, it matters to me too. I mean, if this is a one time situation and someone makes an accusation or says something, our judgment call may be this one isn’t worth it. I’m moving on. So I think that, yeah, in the moment, one of the criteria is, is this. Clearly coming from a place that if I ignore it or avoid it or try and change the subject, they’re going to feel like I brushed them off, which is not what I want to do with my loved ones. Right?

Jonathan Fields (00:26:58) – Yeah. It also occurs to me that scenarios like this aren’t just happening in person these days. They’re happening through screens, they’re happening asynchronously, and they’re happening anonymously sometimes where that person who may you may feel like is, quote, coming at you is actually coming at you through an anonymous avatar in the comment section on a social app.

Jonathan Fields (00:27:21) – And yet there may be vitriol or falsehoods attached to that. And I think that just complicates the issue to a certain extent, because part of what you’re talking about is really paying attention. It’s going back to the interpersonal situational awareness and seeing, can I get a beat on the intention underneath this, on the emotion underneath this, on like really understanding what’s behind this. But in that other sort of context I just described, it’s so much harder to get that beat and understand what is the intelligent response here.

Sam Horn (00:27:51) – Isn’t it interesting? I think this circles back to attention again and it’s like, is this deserving of my attention? You know, Jose Ortega, Garcia said, tell me to what? You pay attention and I will tell you who you are. Right? So if this is a troll who’s getting off on attacking me, I’m not going to give the troll my attention. Right? Because that five minutes, the half hour I could give to this person who is in it to win it, this person is a gotcha kind of person.

Sam Horn (00:28:23) – They’re saying it to incite me. They’re saying it to get me riled up. A response to that person is a reward to that kind of person. They’re what I call a five percenter. They really aren’t looking for a rational conversation, right? That’s not their goal. So I’m going to give my attention over to someone that’s going to be additive, instead of someone who is so clearly doing this because they get off on it.

Jonathan Fields (00:28:48) – Yeah. And I guess when it’s really obvious like that, like that is you can make that color easier. I guess my question is more around when it’s not so clear, because sometimes it’s really hard to read the intention. Somebody just right on the edge, the right on the line. And they may be deeply, emotionally invested in something and really want to engage in a conversation, or they may just be trying to cancel you or take you out, or just see if they can direct some of the attention to them, because maybe it’s going to help build their following or whatever motive they may have.

Jonathan Fields (00:29:18) – And there are really obvious, blatant versions of that, of course. But then I think more and more there are those those versions of it where it’s really hard to tell or to understand. And if somebody truly does want to engage with you, and it would make sense to engage in some constructive way, and then you don’t respond to them, then there’s that quote, brush off effect that you described, which is not the intended impact that you want to have.

Sam Horn (00:29:42) – I think if there’s a different way to say this, it’s, you know, a tension is also the river that’s run through my work. I honestly do believe that. So are we talking about trolls online? Shall we be specific about a troll online? Sure. So if it’s a troll online, then once again we’re making a judgment call. My dad used to say, if someone gives you feedback and other people, a number of other people say something similar, then it has value and you need to take it on board even if you don’t agree with it, there’s something to be learned there.

Sam Horn (00:30:13) – However, if what they say flies in the face of what everyone else is saying, it’s truer of them than it is of you, right? And now, am I going to give the attention to the 99 people who felt this was a good workshop, or the one who had an agenda or an issue? Right. I’m going to focus on the 99. So back on the troll. If, say, if this was a podcaster that you respected and this podcaster said something and you thought, I want and need to take this on board, because that is someone who I believe is very good at what they do, and I admire them. So there’s something I want to be open to. Then I would engage that person. I would ask for a certain amount of their time. I would say, I know you’re busy and you have five minutes for a phone call, or I know you’re busy. And may I ask one question? Because I really believe the clock starts ticking the second we start talking.

Sam Horn (00:31:08) – And if we just engage in a conversation and it has no parameters around it, it can quickly get out of control. And then all of a sudden we’ve gone down the rabbit hole again.

Jonathan Fields (00:31:19) – Lots of guardrail issues there and boundary issues too. You know, as you’re speaking, we’ve kind of been talking in the context of the online world. Literally what came back to me was years back when I was giving a keynote and in the middle of the keynote, a hand towards the back of the room kept raising and raising and raising. And normally, like I wait until I’m done with my spiel and then we have a Q&A afterwards. But this person was very fervent. So, so against my. Probably better judgment, I said. Is there something that you’d like to share that’s relevant to what we’re talking about now? And then came about 60s of venom, and my initial response was I felt attacked and I felt defensive and I felt the need to defend myself. And and then something kicked in immediately after that.

Jonathan Fields (00:32:03) – And what I did was I scanned the room and what I noticed were a lot of rolling eyeballs, and it became really clear to me that this was a person who was known to the audience, which was a a group that meets on a regular basis and has speakers and was pretty clearly known to probably be regularly doing this, judging purely by the response of everybody else who had been in monthly meetings with this person. And at that point I basically said to myself, okay, I know what’s happening here. And I responded with something like, thanks so much for contributing. Like, if it’s meaningful to you, I’m happy to explore this more after the conversation and then just went right back into my thing rather than engaging in any other kind of way. I wonder if so much, you know, you talk about interpersonal situational awareness. Sometimes we get cues from the people who are also part of the experience to really trying to evaluate what’s really going on here.

Sam Horn (00:33:00) – Boy, what a great example. And you are bringing to mind a time I was speaking to naval officers and I was happy at the time, pregnant in Hawaii, right.

Sam Horn (00:33:11) – And named the name for Hawaii, for pregnant in Hawaii supply. And there was a master sergeant and he Jonathan, he literally had his arms crossed and he was sitting in the corner. And the naysayers often sit in corners because they’re apart from the group, right? They have one foot out the door. And so if I had known more this was early in my career, I would have read those signs. This is clearly. And so I was speaking on being a public speaker. And so we had an exercise and he crossed his arms again and he said, I’m not doing it. He said, I’m in a storm form. Well, I tried to win him over, right. And in retrospect, I spent a disproportionate amount of time trying to win him over. And I penalized the other 25 people in the class because they were on board and they were ready to go. So what did I learn from that situation? We’re back to interpersonal situational awareness again, is that if one person, for whatever reason, has an agenda and you look around and the group doesn’t have that agenda, then we give our attention to the group and honor the greater good, instead of being hijacked by one person who’s in it for the ego or whatever reason, but is looking to be the person who throws the wrench in the works.

Jonathan Fields (00:34:29) – Yeah, so much of this keeps coming back to attention and awareness and really just being cognizant of what’s going on, not just on a context level, but a subtext level. What’s really happening here. One of the other things that you explore and you write about is which can be this experience that leads to conflict is the experience of being unseen, being feeling like nobody actually recognizes you, nobody sees the real you, nobody supports you that you’re not heard even when you speak up. You’re not appreciated. Your point of view may not really be acknowledged or validated or valued, and for sure, this can lead to conflict. And I know this does lead to conflict on a daily basis, especially in the workplace, because this is something that people talk about and complain about on a regular share date. About your thoughts on this type of scenario.

Sam Horn (00:35:26) – I was speaking for a Silicon Valley firm, and I talked to a couple of CEOs about, okay, address the elephant in the room, tell me the truth about what people could be doing that sabotages their career success.

Sam Horn (00:35:40) – Because if we don’t know it, we can’t fix it. Right? So one of them said, you know, talk about people who are feeling overlooked or who are complaining that they’re not seeing or giving the advances that they deserve. And I said, well, what’s an example? He said, Sam, we were opening up an office in France, and he said, we have a woman on my team who was a foreign exchange student, speaks fluent French. She’s still in touch with her French family. ET cetera. I thought she’d be wonderful for the role. So we were at the meeting where we’re making our decision to add people to our French team, and I threw her name in the ring, and everyone went, whoo! And he said, well, you know, Susan, Susan’s. And they they went, who? And she ended up not getting that job. And it wasn’t because she didn’t deserve it. It’s because no one had witnessed her in action. And I said, did you talk to Susan about it? You said, yeah, I called her in my office and I explained what happened.

Sam Horn (00:36:37) – And he said, why aren’t you speaking up in meetings? And she said, well, I tried, but it’s just a big jockeying match and everyone’s interrupting each other and taking credit. I just gave up. And he said, Susan, don’t you understand? If you don’t speak up in meetings, people come to the conclusion you don’t have anything to contribute. And when they’re selecting a project leader, someone, you’re not going to get it because they don’t have evidence of your leadership in action. And so what we did in that session is we talked about how in every meeting speak up and it’s always additive. It’s not to complain or I don’t think that will work. Or here’s the problem with this. It’s that’s a great suggestion and maybe we can do this. It’s like kudos to the team for exceeding their quota for the first quarter. It’s just I believe we have an intentional or an accidental brand at work. And if we’re not speaking up, our brand is I don’t know who they are and I don’t know what they do.

Sam Horn (00:37:36) – And we can do something about that now.

Jonathan Fields (00:37:38) – So in your mind, then, the experience of feeling unseen, unheard and valued, it’s not just a one way street. It’s not just that this person or this leader or this manager isn’t getting me, isn’t seeing me, isn’t understanding my contribution. That part of that responsibility is ours. And that’s causing conflict and discomfort in that part of it. It’s on us. Maybe a lot of it is on us to actually say, like, how do we want to show up? Or am I clear? Am I really clear on how I want to be shown up, how I want to be seen, how I want to be heard, how I want to be valued? And am I presenting myself consistently in a way that’s in alignment with how I want that to happen? So giving others the opportunity to actually see and hear and acknowledge me.

Sam Horn (00:38:26) – You’re bringing up a situation I haven’t thought about for a long time, and I realized how pivotal it was to my clarity around this is that I was in the tennis industry.

Sam Horn (00:38:35) – I worked with Rod Laver and then World Championship Tennis, and then I went to work for Open University, and now I’ll use her name because it was a good lesson, is that I took a salary that was half of what I was making before, because I believe so much in this job, and I was just a welcome. I was glad to have it. Well, you know, I was really an initiator. I was initiating new courses. I’d read the Washington Post and oh, why don’t we add this and so forth. So after about six months, I was kind of waiting for that call into my boss’s office. Good job. You know, well, here’s your bonus or here’s your raise or here’s your something. Right. Nothing. Another six months went by. And guess what, Jonathan? I started feeling resentful. I started thinking, you know, why am I not getting paid what I’m worth? Why am I not getting the pat on the back? And I finally went into my boss’s office, and I literally pounded my fist on the desk and said, I think I deserve a raise.

Sam Horn (00:39:33) – And Sandy Bremer, bless her heart, said, you do. I was wondering when you’re going to have the courage to come in and ask for it. And I will always be grateful because. I think it’s naive and idealistic to think that it’s our supervisor’s job to recognize and reward our performance. It’s nice, and sometimes that happens. We can’t expect it to happen. So if we feel we’re not being recognized or we’re not being listened to, then what can we do about it to diplomatically bring our contributions to the attention of our decision makers, and not in an angry way, in once again, in a professional way, so that we’re taking responsibility for our career success instead of leaving it in someone else’s hands.

Jonathan Fields (00:40:19) – So if we’re not doing this, then what’s the why? If we’re not crystallizing what we’re about and how we want to be perceived, why are we not doing that? Because I feel like this is actually a pretty common experience. This is not a one off. This happens oftentimes. Is there a fear underneath that that you see that often stops us? And is it a conflict related fear?

Sam Horn (00:40:42) – Good for you for bringing up fear, right? Is why do we avoid these conversations? Why do we? Our default perhaps could be to resent someone for not giving us what we want, instead of asking for what we want, right? I think that there’s fear of retribution, or like fear being turned down, or fear of being regarded as demanding or whatever.

Sam Horn (00:41:06) – Well, once again, we can get ahead of that. I think that we can often turn a no into a yes if we put ourselves in the other person’s shoes and we ask ourselves, why will they say no? Well, if I give you a raise, I’ll have to give everyone a raise, right? It’s like we’re short staffed as it is. We can’t afford. Why will they say no? And then we bring it up first and then bridge with and. And I understand why you think that or I understand that that’s an issue. And then here’s how we can get around that. Or here’s how we can acknowledge that, or here’s how we can justify the raise by showing how we’re making the organization this amount of money, you know, so that it’s actually taken out of our profits for them, as opposed to seen as an expense. So once again, if we apply ourself to, why will they say no? And how can I come up with valid next steps that will make that moot, that we often can?

Jonathan Fields (00:42:03) – Yeah, it’s the idea.

Jonathan Fields (00:42:04) – And you talk about this in really planning in advance, you know, like thinking a couple of steps ahead. Is that different in your mind. So yes, there’s the thing that says what might they respond with? What might their reasons, rational or irrational, be for potentially rejecting my point of view and the request that I have? And can I anticipate them and think through what would be the response that would actually counter that and actually present it as part of my initial offering? So there’s this sort of like the factual and the planning part of that. And I think that would go a long way. But is there something even underneath that in terms of a more primal fear of how we might be perceived for even asking or for speaking up? You know, are there stories that we spin that are just so beyond rationality that no matter how much planning we think about, we still are going to keep sanitizing ourselves?

Sam Horn (00:42:58) – The question is, how will we brought up right what was modeled for us? Albert Schweitzer said in influencing others example is not the main thing, it’s the only thing.

Sam Horn (00:43:09) – And Tara Conklin said, our greatest work of art is the story we tell about ourselves. So, Jonathan, I think what you’re bringing up is what story was modeled for us, and what story are we continuing to tell ourselves that we may not even be aware of? If what we witnessed growing up was an accommodating or a people pleaser, where someone was always, you know, making sure to keep things nice. ET cetera. Well, then that may be our nature as well. And then we ask ourselves, is that serving us? Are we taking that to an extreme, you know, has it become our Achilles heel because we do it all the time at cost, right. So, yeah, I think that if there is fear, fear of rocking the boat, fear of not being liked, fear of angering or upsetting or offending someone, then we don’t risk it, right? We see it as a risky. In fact, Kerri Patterson said something really profound. She said, do we perceive that telling the truth means we’re going to lose a friend, right? If someone doesn’t like what we say, doesn’t welcome it, that we have put a friendship or relationship at risk, then maybe we don’t say it.

Sam Horn (00:44:26) – And hopefully, though, the purpose of talking on eggshells is there are ways to tell our truth without losing friends. There are ways to have hard conversations where people are open to it, and we come out with a good outcome instead of ending up upsetting. Each other, not talking to each other.

Jonathan Fields (00:44:45) – Yeah. And sitting on your hands. It never gets you feeling the way that you want to feel. I mean, in that scenario you just described. So, sure, on the surface, if you don’t say the thing that you feel like you need to say, the friendship continues. But what’s really happening is like there’s a superficial, like tether between you, but the real bond just becomes increasingly degraded and frayed and eventually nonexistent. And then who cares if you have the facade of a friendship, if there’s no real friendship underneath it, you know, and what we’re doing by not actually sharing what we need to share is creating that dynamic, and then wondering why we feel increasingly alone when we’re surrounded by so many friends, not realizing that they’re actually not our friends anymore.

Sam Horn (00:45:31) – What a profound frame you’re giving this the cost of not speaking up or telling our truth, right? There’s balance in all things, right? And so if we are feeling something deeply and we’re so afraid of angering or offending or upsetting someone that we’re not telling it, then that’s a regret waiting to happen, isn’t it?

Jonathan Fields (00:45:55) – Yeah. Just packaged up and ready for us. You know, I think one of the other things that that a lot of us may be concerned about, and again, this is something you speak about is this idea that we’re going to say our piece and we’ll feel really good about saying it. Okay. What’s out there? Like we say, in a kind way, we see it in a proactive way. We say giving people this proactive grace, which you talk about, which basically assumes benevolence to a certain extent. And, and we think to ourselves, or maybe this is the outcome that happens. Nothing. There’s no change, there’s no meaningful response. We just feel like we’ve said the thing that we had to say, and then nothing comes out of it, which can just be incredibly frustrating.

Jonathan Fields (00:46:40) – And I feel like sometimes we even anticipate that that may be the result. And that anticipation alone stops us from doing the thing or saying the thing. Is that something that you see.

Sam Horn (00:46:50) – One word for that ghost, right? Someone ghost us. Yeah. And it can be a spouse, you know, it can be, you know, whatever. It’s just that they don’t respond. They don’t say anything, they don’t register it, they don’t get upset about it, and they don’t want to know more about it. They just don’t do anything about it. Right. So now is this their type? Is this just the way. Well, like, my dad was emotionally distant, right? He was brought up in a family and in a culture where men did not discuss their emotions. Right. It was considered a weakness and so forth. So if I in the early days, because he actually turned around in the last years of his life, he came to clarity that he wanted a deeper relationship, and that meant talking about things that were wrong, or that meant he’s talking about his emotions or his fears or et cetera.

Sam Horn (00:47:44) – We’re veering into something called Five Percenters because you said an assumption of benevolence. And you are right. I’m a pragmatic optimist. I think that most people are good. I think that most people care what’s fair. I think most people correct and self reflect, right? Oh my God, that wasn’t fair. They were, you know, I was having a bad day. I shouldn’t have taken that out on them. Then there’s five percenters and they don’t self reflect and they don’t self correct. And they don’t care what’s fair. And they don’t want a win win. They want to win and they don’t want to cooperate. They want to control. And ghosting sometimes is an issue of control right. And so if over time there is a pattern of behavior where it is clear whether someone is ghosting us as a means of control or insulting us or manipulating us, then there’s a whole set of different responses on how to deal with five Percenters.

Jonathan Fields (00:48:45) – Take me a little bit deeper into that then, because I would love to think that this is a less common experience than it is, but I may be wrong there.

Jonathan Fields (00:48:53) – So take me a little bit deeper into what some of those responses might be.

Sam Horn (00:48:57) – So I wrote a book called Tongue Fu more than 20 years ago. It’s been sold around the world and so forth, and in the beginning, and they were based on Gandhi, you know, be the change you wish to see. It’s everything we’ve been talking about, Jonathan. It’s taking agency. It’s trying to be a force for good. It’s using language that helps instead of hurts. ET cetera. And in the beginning years, people would go, thank you. Why didn’t they teach us this in school? I’m going to etcetera. Then a trend started to happen. Usually about three quarters of the way through. Someone would put their hand up and say, I agree with everything you’re saying, but there’s this one person, right? And then they would go into someone and you’ve tried everything with this and they fly in the face. Guess what, Jonathan? It was like halfway through the program. Upper and then a quarter of the way in this program and then in the first five minutes.

Sam Horn (00:49:47) – So I think, who knows if it’s 5% of people these days, once again, are not coming from this place of I want to get along with other people. It’s coming from, I want to get my way and I don’t care what I have to do. And so one of the suggestions on how to do if we assess and we think, yep, this is not a one time situation. This is ongoing. Yes, I can see this person does it knowingly and intentionally because it works for them. If we see that knowing intent behind it. Colette said it best. She said the better we feel about ourselves, the fewer times we have to knock someone down in order to feel tall. So if we see this person is knocking someone down in order to feel tall, then one of the things is we’ve been taught to use the word eye, right? I don’t think that’s fair. I don’t like to be spoken to like that. With Five Percenters, the word eye backfires because it ends up being a double jeopardy.

Sam Horn (00:50:50) – We end up taking responsibility for their inappropriate behavior. So I believe in something called do the you. You back off. You take your hand off my shoulder. You enough. Because with people like this, the word you keeps the attention where it belongs, which is on their inappropriate behavior instead of our reaction to it.

Jonathan Fields (00:51:15) – Yeah.

Jonathan Fields (00:51:16) – I’m going to push just a little bit deeper into this, because there may be some people listening to this also who are thinking themselves, okay, I get that. It makes sense to me, and the person that they have in mind is somebody who is close to them, either in their family and they have no intention of removing themselves from the family or removing that person because they have a whatever values they may have around family. Or maybe it’s a work scenario where this particular person has a certain amount of power over them, and they deeply need this job, and they cannot do anything to jeopardize it. Where does that person go?

Sam Horn (00:51:54) – Good. Okay. So can we talk about a personal situation and a professional situation? Yeah.

Sam Horn (00:51:59) – Yeah. Let’s okay. So number one, if it’s a personal situation, we ask ourselves, well, you know, there’s three things we can do when we’re not happy with someone’s behavior. We can change the other person. Ha ha. We can change a situation. As you said, we may not want to leave the marriage, or we may not want to not go back to our parents house or see our sibling again or whatever. And we can change ourselves and we can always change ourself. Chances are, and if we change ourself, we can often change how the other person treats us, which improves the situation. So we can always start with number three. And in a personal situation, I believe in being a pattern interrupt. If this person starts in and they get very intense or loud noise, normally we’re told to turn the other cheek, right? That gives him a bully pulpit. I don’t believe in turning the other cheek. If someone is loud and intense and insulting us instead leaning in, you know they’re trying to dominate us with their angry intensity.

Sam Horn (00:53:00) – And if we make nice with them, we’re rewarding them because we’re teaching them that we’re afraid of them. And the next time they want to control, manipulate is just get angry and I’m going to back down again. So I believe in literally and figuratively standing up for ourselves. You know, this is a domination submission kind of thing. And they often do it when we’re seated and they’re taller than us or they’re standing over us. So if we literally and figuratively stand up and say dad or our brother Bob or our spouse or something like that, enough, I’m going to leave. And and we can pick this conversation up when you’re ready to speak to me with respect, or we stand up and we say, this conversation is over, I’ll be glad to talk about this. And we teach them that we do not suffer in silence, that we do not turn the other cheek, that this does not work in backing us down. So that’s a personal situation. Now, shall we talk about a professional situation? That’s good, because sometimes people say, I can’t do that, right? Because I would lose my job and I depend on this money.

Sam Horn (00:54:08) – It’s very interesting. There are a lot of different responses. One is that there is strength in numbers and there is strength in documentation. Over the years, I’ve had a chance to work with a lot of hospitals and physicians. ET cetera. And over the years, it used to be that some physicians were notorious for abusive behavior. And if nurses or hospital staff complained, sometimes the physician was a rainmaker. And so they were going to do anything to that person. And so they felt helpless. So two things we can do. Number one, when I say document, I mean write down the where did it happen, what was said, who witnesses. ET cetera. And then take it to a decision maker. Because these days, with the regulations and the rules in place, if they have documented evidence of behavior of this person, then they are legally bound to respond to it. Right. Because this is what happened. I talked to so-and-so, and this is date, and a three weeks later and nothing’s happened.

Sam Horn (00:55:14) – They’ll be held accountable for that. So I believe in documentation and I also believe in strength in numbers. So if there are other people who have experienced this as well, then it’s not our word against that person’s word. Right? It’s like, here are three people in this organization who have witnessed this, who have been treated like this, who have been talked to like this. Now we have strength on our side because it’s not just opinion and we’re not complaining. We can take it a step further by talking about the customers we’ve lost or the employees that have left as a result of this. Now it’s a bottom line impact for them, right? And they have added incentive to talk to this individual who may be a rule maker, because they have a number of employees with documented evidence they can act on, and they understand it’s a bottom line loss to them, which is incentive to address it.

Jonathan Fields (00:56:07) – Yeah, sort of like use the structure of the organization and the meta frame of like rules and regulations that need to be abided by to drive towards the outcome.

Jonathan Fields (00:56:18) – That actually is one that lets you be back in a place of comfort and ease and dignity and respect and agency. Zooming out a little bit, what you described, you use the language about your dad. Later in his life, he came to clarity around the nature of the relationship that he wanted to have with you. I wonder whether seeing that evolution with your dad has been a motivator for you to try and create that effect in others early in their lives, so that they can have more time in clarity and connection with people around them.

Sam Horn (00:56:58) – What a astounding.

Sam Horn (00:57:00) – And profound and sensitive observation Jonathan, is, because it’s never occurred to me, and I think you’re right. Is that one of the themes of what you said is the price we pay when we hold our emotions, what’s termed close to our vest or something like that, right? When for whatever reason, it’s not happening and we either suffer as a result of it and have regrets and feel we don’t really know someone, and that the wealth in what matters is when we feel we can be honest.

Sam Horn (00:57:34) – And there’s a free flow right between us that we don’t have to read between the lines, that we don’t have to second guess if so. So you’re right. I think that experiencing my dad that way, because one of my memories of him was that he never cursed. And we were building a corral for my Appaloosa horse, and he hammered his thumb and he went, damn, that’s the only time I ever heard my dad curse, you know? So that is something to admire. Yet it is a thread sticking out of the carpet of how tightly controlled he was around his emotions. Right. So growing up, that’s a noble thing, is to not say something in the moment is to not reveal emotion. Right. And our strength taken to an extreme as our Achilles heel. So I think when he evolved and was more open with his emotions. Now back to what you said. I experienced firsthand that it’s a better way to be with the people we love. And if through my work, we can be that way pragmatically and proactively with other people, then that’s a win, isn’t it?

Jonathan Fields (00:58:48) – Indeed.

Jonathan Fields (00:58:49) – It feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. So in this container of Good Life project, if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Sam Horn (00:58:58) – Well, Jonathan, it’s a kudos to you because I’ve had the privilege of listening to you for years and you are a rising tide advocate for the good life. So your work in bringing our attention to what matters. So first, thank you. And secondly, it is a good life is wealth and what matters. And to me, that’s being close with family and friends, and it’s being active and engaged and additive and appreciative every single blessed day of our life.

Jonathan Fields (00:59:34) – Thank you.

Jonathan Fields (00:59:36) – Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode safe, but you’ll also love the conversation we had with Zoe Chance about the. A language of influence. You’ll find a link to Zoe’s episode in the show notes. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app.

Jonathan Fields (00:59:53) – And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor, a seven second favor, and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life project.