You may know my guest today, Jeffrey Marsh, from their spiritual and inclusive messages that have received over 1 billion views on social media. Jeffrey is a viral TikTok and Instagram sensation, the first openly nonbinary public figure to be interviewed on national television, and the first nonbinary author to be offered a book deal with any “Big 5” publisher, at Penguin Random House.

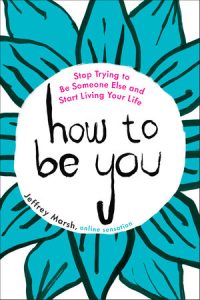

Jeffrey’s bestselling Buddhist self-esteem guide How To Be You, is an innovative, category-non-conforming work that combines memoir, workbook, and spiritual advice, inviting anyone and everyone into the conversation through a lens of kindness and inclusivity. How To Be You topped Oprah’s Gratitude Meter and was named Excellent Book of the Year by TED-Ed. Jeffrey has also been a student and teacher of Zen for over twenty years, and this practice has been central to both their lens on life, and capacity to do the work they do in a grounded, deeply-present, open-heart and joyful way.

You can find Jeffrey at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Trystan Reese about living and advocating for your truth.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:00:00] What I am is a walking metaphor. I hope it’s darn clear what I was told is wrong with me, and I hope it’s also darn clear that I love that. I love that about myself. I celebrate it, I show it, I dance within it and have joy all around it. You can do the same.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:21] Hey there! So you may know my guest today, Jeffrey Marsh, from their spiritual and inclusive messages that have received over 1 billion views on social media. Jeffrey is a viral TikTok and Instagram sensation, the first openly non-binary public figure to be interviewed on national television, and the first non-binary author to be offered a book deal with any of the Big Five publishers landing at Penguin Random House and Jeffrey’s best selling Buddhist self-esteem guide, How to Be You is this innovative, category non-conforming work that combines memoir and workbook and spiritual advice, really inviting anyone and everyone into the conversation through a lens of kindness and inclusivity and how to be you. It topped. Oprah’s Gratitude meter, was named Excellent Book of the Year by Ted-ed, and Jeffrey also has been a student and a teacher of Zen for over 20 years. And this practice, it’s really been central to both their lens on life and capacity to do the work they do in a grounded, deeply present, open-hearted and joyful way. So excited to share this best-of conversation with you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:26] And a quick note before we dive in. So at the end of every episode, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard this, but we actually recommend a similar episode. So if you love this episode, at the end we’re going to share another one that we’re pretty sure you’re going to love too, so be sure to listen for that. Okay, on to today’s conversation. I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:57] There’s so many different fun places that I want to go with you. I’m thinking almost like a bit of a three-act play. Um, if you’re cool with that, I’d love to take a step back in time, explore some of your early life. Then I thought it’d be interesting to dive into language and identity, because I think it’s a really interesting conversation. And then I’d also love to explore some of the bigger ideas and concepts that you’re regularly talking about that are from your book as well. Does that sound good?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:02:21] What if I was like, no, I’m out of here? Yeah, those are all my favorite things.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:26] Awesome.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:02:26] So I’m ready.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:27] That sounds great. So. So as we’re having this conversation, actually, where are you right now? Where are you these days?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:02:33] In beautiful, sunny Los Angeles.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:35] Ah, nice.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:02:36] I was a New Yorker from for many years myself, so.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:40] Yeah. Well, okay. So now I’m curious. Whenever somebody goes from New York to LA, I’m always curious what the motivation is behind that.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:02:47] Weather.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:48] Ah. All right. One word.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:02:51] Well, that was partly it. I mean, I actually didn’t think that the weather would affect me as much as it has, but it’s 72 and sunny today. Um, and that doesn’t hurt. But it was mostly for a career for making TV and doing TV stuff.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:08] Yeah. That still is where so much of the, the industry is. Um, but you grew up not too far from New York. Well, geographically, not too far, but it’s sort of like a different universe in a lot of ways. Um, your county PA, for those who’ve never heard of that or have never been there, I’d love if you could paint a little bit of a picture of what the area that you grew up in was like, especially when you were a kid.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:03:30] It was the woods. It was a large farm, um, over 300 acres of a farm, which means I got to run around and play. But I also didn’t have much contact with others with other people. One of my main sources of social interaction was the church and the church that I happened to attend during high school with my parents was also the clan meeting house. So the clan would meet in the basement, and, uh, we were not members, but, um, that was going on in the building. So it was a very, very conservative part of Pennsylvania and a place, you know, I was growing up in a place where I wasn’t even sure if there was anyone else like me, um, at all.

Jonathan Fields: [00:04:22] Tell me more of what you mean by, ‘like me’.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:04:25] Uh, specifically, you know, in my head, as I said it, I meant nonbinary. But beautifully rainbow, LGBTQ imaginative. There were a couple years where I really, literally thought maybe I was born on another planet and was sent somehow to Pennsylvania. I don’t know if you wanted to get this deep this quickly, but I have a bit of a reputation for doing that. You know, I was told basically in many ways when I was a kid that I was worthless. So one of the narratives I had was, well, actually, I’m very special. And it took me many years to come to the realization that every single person is special. That specialness is something that includes everybody.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:18] Mhm. When you get that message as a kid, which is a devastating message to get at any age, but especially when you’re really young, when you know the likelihood of you having resources available for you to understand how to process that in a way that isn’t any way constructive, that just doesn’t exist in most kids, let alone most adults. Right? How does that land with you? How does that affect the way that you move through your life, the way that you see yourself, the way that you relate to others at that moment in time?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:05:51] I spent so many years deeply alone and feeling deeply lonely. And the interesting thing, and the reason I love so much what I do today is that as a kid I imagined. A beautiful, loving family. It’s sort of like, um, I don’t think it was exactly like this, but it’s imagining the family I had. You know, where I was born on Mars, right? I just imagined this loving group of people who accepted me exactly for who I am and how I am. And I had enough agency as a kid to be able to imagine that. And so when I became an adult. And literally found that through social media, through community, it had such a deeper resonance for who I was as a kid. I had, in a way, trained myself to recognize who were the good-hearted people. Does that make sense?

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:59] Yeah. I mean, it’s, um, it makes a lot of sense, you know, and it doesn’t have to make sense to me, even if it didn’t. You know, this is your. This is your truth. You know, it sounds like one of the ways that you also felt okay was, was effectively to create your own worlds when you were a kid, your own experiences. I know you write about and you speak about and you talk about, you describe, you know, effectively creating your own, your own world, your own theater, um, your own play, acting in a barn where this becomes like your, your almost escape, like your place where you can be okay, but it also sounds like it was something that you that existed only for you. You kept secret for a long time.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:07:39] Absolutely. And one of the hallmarks of it was always keeping an ear out for, uh, the sound of my dad’s boots on the gravel that was outside the barn. Uh, you know, this constant split in my soul of being totally free and playing and twirling and dancing around and wearing dresses that I had bought or that I had borrowed, you know, and kept in a trunk inside the barn, um, literally playing dress-up long after you’re supposed to not do so. But also having part of my soul, part of my heart, split off to make sure I wasn’t going to get in trouble. And I. It’s a years and years for me to give up that second part, to stop worrying about whether I would get in trouble and to fully embody who I am. This is why when I talk about inner child work, I talk about my inner child rescuing me.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:38] Mmm.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:08:39] A lot of people talk about parenting their inner child, which is lovely, but my inner child kept the innocence and the fun and the idea of joy. That was really earned by that kid. You know, looking back. And that was kept in place, as you know, my inner child, to speak about it metaphorically. My inner child was a bookmark of that joy. And thank goodness you know that I had something to come back to and to reconnect with as an adult.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:12] Such a powerful way to look at that. When you use the phrase ‘get in trouble’, you were you didn’t want to, quote, get in trouble when you heard the boots of your dad coming. What do you mean by that? In your mind back then, what was getting in trouble to you?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:09:26] It meant several things. On a practical level, there was no adult that I can remember in my life who didn’t want me not to be me. And every adult people at church, school teachers, um, parents tried everything they could think of to get me not to be this beautifully LGBTQ. And that included withholding affection. That included violence, that included, uh, social, uh, you know, hints, uh, jokes at my expense, at anything. Anything at all. And on an even deeper level than those sort of tactics. I think what getting in trouble meant to me as a kid was that I would be even more isolated, that I would be rejected, left out of the group, left to fend for myself, that kind of thing.

[00:10:25] Mhm. When you were that age, growing up in that community. Were there any other? People that you could look to. Were there any other role models? Was there anyone else where you could look and say, oh, there’s someone I can relate to. There’s somebody who seems like they’re similar to me and and living life in a way that felt good. Or was it something where you really had no access to other people like that?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:10:55] For years and years, I felt deeply lonely and didn’t really have access to people like that. And then, you know, all of a sudden you’re a teenager and you see a picture of David Bowie and you’re like. What is that? What is that person doing over there? What is that? That’s what I’m doing. Where did that person come from? You know, and I guess it’s deep and poetic and beautiful at the same time. That one of David’s personas was. Was someone from outer space, right? This kind of feeling of you’re the only one. So David Bowie comes to mind. Rupaul was on TV. Um. There is an author named Kate Bornstein who wrote a book called Gender Outlaw. And that book came out in 1996. It’s actually it gets even better. It’s called Gender Outlaw on men, women, and the rest of us. And that came out in 1996, and I was on my way going off to college. And that book changed my life. So a little bit later in this, those teenage years, I began to connect a lot of the dots and and find a sense of community.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:08] Mmm, but it does sound like a lot of that community. It wasn’t local. It was. It sounds like it was more there were people in the media. There were people out there where you saw, oh, okay. I can relate to them in a lot of different ways. I can relate maybe to the community that they seem to be existing within. But that’s not here. That’s not sort of like my immediate experience. Um, if I have this right. Your mom was also a Lutheran pastor at the time, right?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:12:38] Correct. Yep.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:39] And you describe, I guess it was when you were 11. Um, a moment in the car where you decide it’s it’s time. It’s time to tell my mom what I’m feeling. I’m curious what was happening inside of you in the minutes. The seconds before. You said those words where you said, you know, like, mom, this is what’s happening that made you feel like this is the moment, like, I have to do this now after really secreting it away for all of the time. Before that.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:13:14] It felt like a pressure cooker. I mean, it was a jumbled mess, but the only way I could conceive of to be comfortable and to be happy was to inform the most important people in my world. And my mom was obviously included in that. And at the time, all I could come up with was, I think I like boys, uh, because I was the only reference point that I had. And I would end up coming out to her again at 16 and again at 18, and it would be a rolling process on into adulthood.

Jonathan Fields: [00:13:51] Mhm. When you use that language, and I guess as you just described, that was the only language that you had at the time. You know, it’s interesting and I think this is probably a good transition into just really exploring language and identity, which has become such an emerging part of the conversation, the public conversation I think over the last really five years or so. But before we get there now, I’m really fascinated by this book that you say hits in 1996. Right? Because literally having, if not the word non-binary, but the expression of that identity in the title or the subtitle itself in 96 is a profound act. Mhm. Because that is not part of in any meaningful way, the public conversation at that moment in time. I’m curious now also when you dive into that book, you know, now a number of decades ago, um, what’s that experience of?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:14:47] Thanks for the reminder.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:50] Um, what’s that experience like for you? You know, because I’m wondering if that is that the moment where you start to say, okay, so I’ve been I’ve been trying to figure out what is the language here for a long time, but not just the language. What is the sense of identification and who I am underneath it?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:15:05] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:06] What was the role of that book in sort of like deepening you into that exploration?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:15:10] Well, the to put it simply, the book saved my life.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:14] Mm.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:15:14] It was a process of starting to see myself less and less as a freak. And looking back, you know, for a book to have so much power, it wasn’t necessarily, oh, there are gender-enthusiastic people in the world. There are gender-delightful people in the world, right. Or whatever language you want to use. There is something beyond man and woman, as the subtitle says. But it it’s it’s not just that it’s not. It’s not just technical vocabulary. It’s the idea. That I didn’t have to fit into what I was told. The only possibility to be a human being is. So there’s something technical like, yeah, this movement exists. But it’s also something mind-altering. That there are people who literally think differently on this planet. And I guess part of what was so transformative is I can go find those people.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:18] Mhm. The 90s is also a really interesting time for you to be grappling with this and sort of like figuring a lot of these things out, because this is a moment in time where HIV, where Aids is this absolutely terrifying, terrifying thing that seems like it is overtaking communities, that it’s literally just was watching the new piece tick, tick boom on Jonathan Larson’s life. The playwright behind rent and being a longtime New Yorker, I remember being in New York and being downtown and being in the East and West Village and like, like knowing all of the people who are in the play and also having friends and seeing so much addiction, so much loss. Um, so this has got, you know, this is all something that’s going on as you’re sort of like trying to figure out, like who I am, where, where is my place? Is there a place for me? Was that a part of what was spinning around in your head during that whole sort of like, 90s window as well?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:17:24] Yeah. I mean, I can remember being on the farm as a very young kid in the early 80s and seeing the news talk about the gay plague. And seeing Rock Hudson die and all of this stuff that as a very young person, when I was aware of who I am, that being associated with loneliness, being a pariah, rejection, death, uh, it can get heavy. And at the same time, you know, I’m glad you brought up Jonathan Larson, because throughout rent especially, is this lightness. Living for today is part of the message. And I also got that. It’s hard for me to go back and piece together, you know, pros and cons list of what? Of growing up the way I did. You know, you said, um, figuring it out and. I get asked a lot in interviews. When did you know you were different? Sort of this stock question. And I always give a very lovely slash sassy answer that I never felt different. What I did come to realize is that other people had a problem with who I am. But that’s not to me. That’s not the same as feeling like I’m not a human being like they are. I’m not. I don’t have the same wants, desires, um, need to belong, that sort of thing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:00] Mhm. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:06] When you come out to your mom then and then again and then again during this sort of like window of time. It occurs to me also that like for her as a, as both somebody who is devout, uh, somebody who is a parent, somebody who exists in a particular community with a particular set of norms and beliefs. She’s got all of those sets of concerns, and at the same time, she’s got to be seeing all the news, also seeing all the same stories that you’re seeing. And I’m wondering if in the back of her mind, part of what’s going on is also like, this is my kid and is, is this the life that my kid may be stepping into? And like, I love my kid and I’m really just concerned for their well-being. I’m curious whether you’ve ever had that conversation with her.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:19:54] Why, as a matter of fact, we have had that conversation and she yeah, she was flat out. So when I told her at 11, she said, you don’t know what you’re talking about. You’re too young to talk about these things. Don’t ever talk to me about that again. And she was screaming and very upset. And what I received as an 11-year-old kid was, wow, this thing that is inherent that I can’t change about me is awful. Is evil, is my fault. I gotta hide it for the rest of my life. Just the most terrible slamming sound of the closet door in my face. And years later when we talked about it, she said, I was scared that you would get HIV. I was scared that you’d be alone for the rest of your life. She said that her biggest motivating factor was fear. And at 11 I couldn’t comprehend that. And. You know, I kind of. I kind of wished, um, I don’t usually ever talk about this, but I. I wish she could have told me that at 11 years old. It was nice to hear it at, you know, 30 or whatever. I was when we when we talked about that. But in a way, the programming had already been done and that’s really unfortunate.

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:21] Mhm. Yeah, because I mean then it’s it doesn’t land as there’s quote, something wrong with you or quote like all the other ways that it could land as a young kid and even as a young adult, it’s more I’m concerned I’m concerned about you being okay as a parent, which is a profoundly different message.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:21:43] Yes. And I actually heard from both of my parents later in life, you know, after I had left home that they felt it was good parenting to get me not to be LGBTQ. In the sense that they were saving me from some horrible, lonely life. Disease-ridden life. And. It’s hard to argue with that. Because that’s what the culture was telling them. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:15] And at the end of the day, you know, it’s interesting. You ask the typical parent what they want for a kid, and most of them will rattle off some variation of, oh, I want I want my kid to be happy. Um, but the deeper truth is, before even before that, what you really want is for them to be safe. You want for them to be okay. And sometimes, you know, that’s how we map that is guided by. The culture, the ethos, the philosophy that surrounds us. It’s all. It’s all we know. Um, and so it’s like the intention is actually not a bad intention, but the way that we think is the appropriate way to go about it ends up causing harm that we don’t even realize is being caused in real-time, and sometimes not until many years later.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:23:00] Yeah, a lot of parents come to me to ask how they can support their LGBTQ kids, which is a wonderful thing. I love always getting those messages, and I have a bit of a shocking answer to that one. And it’s as a parent, you need to love yourself. You need to accept all of the things that you find unacceptable about yourself, and then demo what that integration is like for a young person. And I never, never wished that I had a perfect set of parents. But a more, um, consciously loving set. And I mean loving themselves. To have seen that when I was a kid, I think would have been something quite magical for me.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:58] Mhm. Yeah. It’s so powerful. Right. Because it end of the day it really doesn’t matter what you say as a parent it matters. The behavior that you model is what sends the most powerful message. And you can’t walk around all day saying this this this and this and then do the exact opposite and move through the world in a different way. It’s like kids,

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:24:18] You should love yourself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:19] Right? It’s like, yeah, and then go do all sorts of self-destructive things to yourself as a parent.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:24:24] Right. Exactly. You don’t have a leg to stand on.

Jonathan Fields: [00:24:27] Yeah. So when you move out into the world and you start to be able to actually say yes to your own community, say yes to your own sense of identity, say yes to your own language you described earlier when like that 11-year-old moment where you tell your mom, I think I like boys, that was the only language that you really had at that moment in time. But that’s really it’s changed. It’s evolved and it’s expanded. And that language in the early days was really, um, sexual orientation focused. But the language now, not just you, but sort of like that. There’s been this really powerful evolution of language. And I don’t want to say evolution of identity because I, we’ve always been what we’ve always been, and there have always been people of all identities and all sexual orientations forever. But now it seems like there’s been this evolution in granularity, in language that allows people to really figure out, like, what is the language that allows me to express myself differently. I’m curious how you how you have sort of explored the world of finding the language that felt like you.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:25:36] Oh goodness. I mean, it was just a bunch of it was it was a. Playground. It was a hodgepodge of trying different things. Uh, yeah. I cycled through lots of different stuff and. I was on vine and I was famous and doing videos on vine, and the kids on vine said, what are your pronouns? Are you non-binary? This was like 2013 and. I was like, what are these kids talking about? And so I went to the source. Everyone at the time would go to Tumblr.com, and I looked up, you know, what are these kids talking about? And I started reading personal experiences of people who were non-binary. And the light bulb went off. I felt so comfortable and at home and at peace with that. And because of the kids, as I like to say, I became one of the first public figures. I was the first person to talk about it on national TV, being non-binary and talking about sort of this modern era of the pronouns and, and how to treat people like us with the most respect.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:52] Mmm. Talk to me about that relationship between use of appropriate pronouns and respect, because, um, I think that’s one of the things that people will sometimes struggle with. They’ll they’ll think, oh, well, you know, like quote, why does it matter so much what pronoun I use? But it’s really not a language thing. It’s bigger than that.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:27:15] Yeah. It’s that, it’s that a statement? Was there a period or a question mark?

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:19] It’s kind of like a little bit of a lingering question.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:27:22] Okay, good. Um, that my favorite, my favorite kind. Um, I to me, it’s about a human soul. So a label is not the totality of a human experience. But it is a place for someone to land, to feel seen, to feel understood, to feel respected, to feel loved, to feel accepted, to feel the thing that I was craving the most when I was nine years old. On the farm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:55] Mmm. I mean, it occurs to me also language is. It’s a way to communicate what’s going on. It’s a way to communicate your inner life, your inner experience, your inner sense of identity, of who you are. And when you don’t have that language or when it doesn’t quite fit, it’s almost like, and tell me if this is completely off or if it resonates with you. It’s almost like you’re 80% seen, you’re 60% seen, but you’re never quite fully seen or expressed because the language is never quite accurate. Does that in any way resonate?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:28:33] Yeah. And until circa 2013 on Tumblr, I didn’t have that level of comfortability.

Jonathan Fields: [00:28:42] Hmm.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:28:43] It’s kind of hard to explain if someone has been comfortable in their label their entire lives and. I think this this, this this is one of my favorite, um, references. Gene Hackman is an actor, and he, he has talked about in interviews about how he doesn’t even think of himself as a good actor, just a comfortable one that he’s been in like 40 movies. And so his 41st one, he’s just going to walk on set and know exactly what to do. And the I. The concept of having language that truly sees a person is that level of comfortability. It’s a level of goodness. It’s a level of human relaxation that is hard to describe if you’ve never been through it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:34] Mhm. So it’s not just respect. It’s about I mean it’s a yes and it’s respect and ease to a certain extent.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:29:42] Yes. That’s the perfect way to say it. Yeah. Respect and ease. Which as you’re saying it, it seems a little, a little ironic to me because people usually have a little time where they are not at ease trying to learn the new pronouns. Right. So it’s a little bit of like, bumps in the road until everybody is at ease. But that does eventually happen. And it’s beautiful.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:08] Yeah, I mean, it’s interesting. So I’m 56 and, you know, I came up in a world where, you know, the teaching was, you know, there are these two things and names were assigned based on that. And those two different states, you know, like male, female were assigned to a being at birth generally. And then you reference them throughout life that way. And it is interesting to me because we live in a very different world, which is an amazing thing right now. Not that, again, not that people are different, but that there’s an openness to actually acknowledging. That there’s more than this binary state, and that there’s new language that really helps people step into and express, like whatever, wherever they are in the spectrum, in gender. And like you said. And yet at the same time, I still stumble on a regular basis. And I think a lot of folks listening to this have that same experience of stumbling. And the fear is always I always want to lead with dignity. And so sometimes I will default to just not saying anything rather than saying the wrong thing. And I often I feel like there’s that fear in so many people is that you don’t want to do harm, and that misgendering it can really do harm. And I wonder if there’s sort of like, we’re in this. I feel like we’re in this moment right now where people are trying to figure out like, what is the what is the the way to step into the conversation on all sides where dignity and doing no harm are at the center of it all. And I feel like we’re all stumbling in a really big way through that conversation in real time together.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:31:52] And thank goodness. Thank goodness. Because if we were un stumbling and if we were comfortable when people were not being respected or included, then I think it’s probably a good thing to be uncomfortable. You said it so beautifully. That this is a process with an end goal that is noble, that is beautiful, that is human connection. And it’s such a delight to speak to you because so many people want to get bogged down in the rules. And don’t realize the spiritual aspects. Not that a person has to have a spirituality, but when I say spiritual aspects like a like human dignity and respect, right? Because the danger has been. As non-binary folks, we’ve gone from people thinking we’re absolute weirdos, not wanting anything to do with us, to now people being afraid to say the wrong thing around us. And in both instances we are left off alone with nobody to hang around with, right? People are afraid of us because we’re weird, or people are afraid of us because they’re they’re going to say the wrong thing. And one encouragement I would give is. We have encountered this many. You know, if you’re talking to a an out non-binary person, we’ve encountered this many, many, many times. And yes, it is not pleasant to be misgendered. It’s not pleasant when people forget, but. You should be included in that common human dignity and respect as well. Meaning I, as a human being, don’t want you to spend three days feeling bad. Because you said he. That doesn’t seem very productive to me.

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:07] Yeah. And at the same time, right, as you just described, what’s what’s the alternative is if you just if you’re so fearful of making of saying the wrong thing, of making a mistake, that the behavior that you choose to adopt is just to opt out of the conversation entirely, you’re doing harm by basically engendering isolation, by creating separate worlds, by almost implying like there is. I’m so uncomfortable with being wrong that I’m just going to, like, opt you out of my experience of life, of community, which inadvertently is just an entirely different way of doing harm.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:34:54] Yes. And it’s a repeat of what we might call the old days when people just purposefully cut us out of society. Yeah. And the conversation altogether.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:05] Right. It’s like the net effect is the same and the intention may be different, but the net effect is the same thing. Yeah.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:35:12] And I always like to remind allies that you will goof. It just is going to happen. And being able to do that and recover in as graceful a way as possible is part of being a warrior for equality on this earth.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:34] Hmm’hmm. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:40] The other um, interesting evolution of language is I think gender has been really cool to watch how the conversation has shifted around it. And the other part of it is sexual orientation. There are a lot of new phrases, there are a lot of new identifications, and I feel like there’s kind of some fun being had with language along the way, too. I think I think is gender fun, even sort of like part of the. So there are so many variations now, um, that, you know, I think, you know, you’re talking about and granted, there’s more than just male, female and non-binary or on the gender side, also, there’s a full spectrum of identifications. And now we’re seeing that in sexual orientation also. And I feel like a lot of times people also still conflate sexual orientation and identification with gender and make assumptions that if you’re this in one of those categories, then you must be this in the other. And yet there is like a beautiful amalgam of mix and match, you know, like whatever tapestry you want to put together that feels fully expresses you. It seems like there’s this availability to pick and choose the language that continues to evolve in a really beautiful way from the outside looking in again, talking to you, as, you know, like a straight cis-gen midlife guy. Um, does it does it feel like that? Um, from your lens, from your experience?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:37:07] Yeah. Are you talking specifically about the kids on TikTok that, kind of vibe?

Jonathan Fields: [00:37:13] That, but also just like in common conversation these days, just like I feel like there’s been an expansion, like it started, sure, in certain areas. But now, um, even, you know, it’s interesting, right? Because even the word queer, I think is really interesting because that word I’m seeing used in so many different contexts now, sometimes without even reference to sexuality. And I think it’s just fascinating to see how people are playing with this language and just adopting it to mean whatever it is that they feel somehow just resonates with them.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:37:45] Yeah. And it goes to show you how woefully inadequate language is to describe human lives, let alone behavior. But you know, you’re the way you encounter things and how you feel and and all of that stuff. Language is just not adequate. And you highlight the invitation. I don’t know if you meant to do this, and I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but, you know, someone like me is an invitation to folks who have never. Uh, never thought twice. About the labels they use. You know, for example, you use the word cis, meaning cisgender, the opposite of transgender. And even to use the word opposite, like, what am I talking about? You know, but it for someone who never even encountered the word CES because they just thought of themselves as a man from start to finish, and that’s been their whole experience. The invitation for me to someone like you, and again, correct me if I’m wrong, is your box doesn’t have to be so small and proscribed either. That men don’t have to spend an inordinate amount of time trying to be the meanest man you know, or whatever the version of that is. That the comfort and play and genderqueer nature of human existence as a non-binary person can be, you know, you can come to this playground, you can come to this, this field over here and hopefully find some some peace and expansion yourself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:32] Mhm. I like that invitation.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:39:36] Yeah, and it’s never. I never. So a teenager will, you know, comment on one of my videos and say, is it okay if I’m a non-binary lesbian? And I say, of course, right. It’s kind of like what you were saying before. It’s like, uh, we’re we’re making this up as we go along, and I’m perfectly fine with that. And if there’s a word or a set of words that you love that help you to feel seen and understood, even if that’s man or woman or something, you know, a label that’s that you’ve used and has been common your whole life, you know, even if that’s the case for you. Hopefully you still find comfort in the idea that you don’t have to have a standard. You don’t have to meet a standard of who you are. With sexuality or gender.

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:32] Yeah. I mean, I think that’s it’s such a powerful invitation for everyone, you know, and I think it’s I love the reframe and I love you and, you know, like reflecting that back to me because I offered, like, this certain idea to you unwittingly kind of like opting out of the same exploration. And so you reflecting it back to me is like, you know, right? Right. No, I got it. It’s all good. You know, it’s like we’re all in this dance together, you know? And like, don’t ever assume that you’re on the sidelines trying to figure out, like, what quote they are trying to figure out.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:41:09] You just excited me so much. Because allies will ask me, how do I respect non-binary people? And I’ve started asking, well, what are your ideas? What are you coming to? What are you coming to the table with? Because you’re in this movement to right of liberation. If that’s what we’re doing, you belong here too. You helped me just now, right here in this podcast recording, identify why I’m uncomfortable with this kind of expert model of I’m supposed to tell people what’s up. You know, it’s I don’t like that feeling at all.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:45] Hmm. I get that. Um, I want to shift gears a little bit. Also, maybe it’s not a shift gears, but it’s just another point of curiosity for me. Um. You at some point, and you probably picked this up because I used the phrase do no harm earlier. There’s a Buddhist side of you. I’m curious what brings you to that a bit further into life?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:42:09] Well, as a young person about, oh gosh, trying to do the math in my head over 20 years now ago, I was so intensely devoted to self-hatred and self-judgment. When I say I did extra credit, I worked on it on weekends. I did everything that you could do as a young person in my 20s to hate myself almost out of existence. And so things got so desperate that I needed to move away to a monastery for a while, a Buddhist monastery. And have a chance to look at. What exactly we are doing here and what we may be trying to do and why? Honestly, why self-hate and other hate is such a huge. Issue and I happen you know, I wrote about this in in How to Be You, but I happened to study with the person that that first used the term self-hate in a spiritual context. And she. Was. It was brilliant to study with her and take a deep look at why and how. More importantly, how that happens.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:28] Why Buddhism? I mean, there are.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:43:30] I’m lucky.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:32] Because there are so many places that you could have chosen to step into so many different paths, so many different ideologies, philosophies. And I’m always curious why that, especially given the context of like, you know, you you grew up in a particular tradition, like a faith-based tradition.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:43:50] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:50] I can understand why there would be a lot of friction there when you’re sort of saying, I’m in a really dark place, like self-hate is effectively become my religion, and I need to choose somewhere else to step into to figure this out. There are so many different choices you could have made. I’m curious why that particular choice was made.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:44:09] It chose me. Self-hate had become my religion. Yes. Thank you for that. Thank you for the gift of that beautiful phrase. It had become my religion and addiction. Uh, my family, my everything. My world. And I went into a spiritual bookstore in Philadelphia. And across the bookstore was a book, a handwritten this, this weird, like, artsy handwritten font. On the cover of the book, it said, there is nothing wrong with you. And it was written by the guide at the at the monastery that I would eventually go to and train within. But of course, I saw the cover of that book. There is nothing wrong with you. And my brain started going, oh yeah, right. I know this is wrong with me and this is wrong. It started like, you know, do you want the alphabetical list or order of importance of what’s wrong with you? Right. And as my brain is doing that, my feet are like, walk, walk, walk, walk, walk over to that book, cracked it open and and through whatever miracle was able to take in that message. For at least a glimpse, you know, just a moment in time. Enough to set me on that. That path. Do you know who Guan Yin is?

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:30] What? Guan Yin as in the goddess?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:45:32] The bodhisattva. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:33] Yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:45:34] This Buddhist figure.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:36] Right.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:45:37] Statues of Guan Yin have had. Boobs, mustaches sometimes both together, sometimes like this angelic being that has no gender and a lot of the stories, depending on which country you’re following that particular deity through in the history of Buddhism will take many forms, many genders, to help someone reach Nirvana or become more enlightened. So there is this tradition already built into Buddhism that transcends, I don’t need to tell you, transcends the identity. But also helped me to become much more comfortable in this gender-transcendent space.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:23] Mhm. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And that was actually one of my curiosities because there is and it’s not only in Buddhism, I feel like it exists more in various eastern traditions than Western-based traditions. There is much more comfort with the idea of dissociation with any particular gender identity, almost shapeshifting. And, you know, it’s it’s just a part of the storytelling, the mythology, the ideology around it in a much more natural way. And I also feel like it’s it’s also that way in the art and the culture of a lot more eastern traditions as well. And it’s sort of like Western said. Mhm. We need to lock this down. Um, and you know, so I’m always fascinated by that divergence, you know, in, in how people storytell about themselves and the world and how the traditions have evolved sometimes over thousands of years around that.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:47:16] Yeah. You know, another prime example is indigenous cultures in North America too. But yeah, I like how you said. Western culture. What was the phrase you used? We need to lock this down. I think it is a in large part, you know, I didn’t know I don’t know how philosophical about gender you want to get, but it does have to do with power struggles and hierarchies. And I didn’t get to say this earlier, but the first suggestion. Of using a gender-neutral pronoun came from women from feminists in Ms. magazine. So there is this concept in 1971. So there is this concept of undermining the power structures in the hierarchies by using more inclusive language that comes long before this language we’re using now about non-binary identity. And to me, it’s all of a piece. We’re going for true equity for folks.

Speaker3: [00:48:19] Mm. When you decide to basically say, I’m going to step in the world as me and I’m going to fully own it and then step into social media and then start to really storytell and share ideas and share who you are in a very bold public way. You also really start to develop a lot of your own ideas and share them. That leads to this fantastic book, How to Be You, which is almost like I feel it’s almost like your your Ten Commandments. Um, but I don’t want to call them commandments, because that would assume that they would always be static. And I feel like even that is sort of like not the intention behind it. Like, this is a dynamic, a dynamic set of thoughts and let’s have a conversation about them. So many fantastic thoughts around perfectionism and cultivating deep trust of yourself and really a devotion to self-knowledge, self-awareness, self-inquiry. Among the topics that you explore, which I thought was fascinating, was the relationship between punishment and control. Talk to me about this.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:49:21] Yes. You know, I realized through my own, how would you say it through my own self-hate journey, uh, that if I was always the worst person in the room. I was able to have some sense of control, some sense of normalcy, some sense. If it was always my fault, then at least I knew whose fault it was. And I don’t know where it came from. Bravery, gumption, desperation to be able to step out of even the idea of whose fault is it? And the undermining of a sense of control or a sense of even consistency that you give up with that. Yeah. From one Buddhist to another. How do we know ourselves? Well, we’re the we’re the people who are terrible, right? We’re the people who are always striving to be better and self-improve and you know. Well, if you have no self, that’s not a problem, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:50:28] Hmm. You talk about the myths of control? Also, as part of that conversation, this idea that control is actually even a thing that that it’s, um, that it’s possible to be in control, that it’s possible to be in control all of the time, that there’s a should involved in it. You actually should be in control all of the time that there’s something wrong with you, that if you’re not or if you can’t constantly be in control, that, uh, you should do something to have more of it. And, and that other people have this magical state, which is a should an aspirational state and you don’t. So much of this is built around this notion that we are we exist in a world that is. I’m going to go back to that phrase, lock down a ball. And it’s like, the more that you assume that everything is within your control, it’s almost like you are inviting suffering into your life, you know, because the reality of the world is it’s not. And yet and yet this is our default approach to everything in life. And I wonder, I often wonder why that is. Like, why do we why do we seem to arrive into adulthood with this wiring which is so slanted towards suffering?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:51:51] My teacher at the monastery used to flat out say. It’s not what, it’s how. It’s not the circumstances of of growing up, uh, non-binary or not, or on a farm or not. Uh. It’s how we build a life, how we are taught to treat ourselves. And I have never encountered someone who was not given the message in one way or another. There is something wrong with you. I. [exhale] I mean, they don’t call it intergenerational for nothing, right? So happened our parents happened to their parents. Happened happened happened. Happened, happened. And I admire people like you. And a lot of my spiritual heroes who say, well. The buck stops here, then. I might not have been given those skills, but I sure am going to go find them somehow, by hook or by crook. To end this cycle somehow.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:59] Hmm.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:53:00] I think it’s one of the most noble things a human being can do.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:04] And by the way, I haven’t yet opted myself out of that cycle. I’m still struggling with all the same stuff as much as I.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:53:10] Come on.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:10] Read as much as I. I know all the things. But like, I’m human and right there with with everybody else listening, like we’re like, let’s still a lot of life that I want to like say, oh, I can map this, I can figure it out, I can there’s a, there’s control that I have over it. And for the most part, for me in the context of my life, it’s it’s over the the nature of the relationships with people that I can’t imagine moving through this season on the planet without, you know?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:53:40] Mhm.

Jonathan Fields: [00:53:41] And yet, like, the truth is always impermanence. And uh, you know, everything is sort of like in perpetual flux. Um, you follow up in your book with like one of the other big ideas really kind of follows nicely with that, which is to get used to not knowing, you know, which is that there is a certain freedom, like, not only is there, you know, like the renewal, there’s a, there’s a freedom in actually not having control in not knowing all the answers and just surrendering to the fact that, oh, yeah, like, stuff’s just gonna happen and I’m gonna get asked something in a big meeting and have no idea what the answer is. And the notion that there’s freedom to that is a little counterintuitive. But if you kind of just, like, sit with it, it’s like, huh? Well, what if there was?

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:54:28] Did you say I’m gonna get asked something in a big meeting and not?

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:32] Which is really funny because, like, I don’t, I don’t have.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:54:34] Is that your big fear right now?

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:35] I don’t have big meetings. I’m sort of like I’m postulating

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:54:39] I was gonna say, how many zooms are you on? Right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:42] Yeah. Like. I’ll be in my suit and tie and all of a sudden I’ll be like.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:54:50] Uh, I think that would be fun to do a zoom like that with you. But as long as it was, you know, a game, a play. Um, yeah. No, that’s that’s that’s. So first of all, it’s true. You can’t control anything. But second of all, once you give up on trying to, that’s what you get. Freedom! Happiness! Ease! Joy! Jokes! I get a lot of hate. As you implied earlier, you know I am on social media and am an LGBTQ person on social media. And you know, I used to not be able to really, uh, not not shockingly, but, you know, it used to be very difficult to kind of psychic weight of everybody really telling you the most awful things that, that you’ve ever heard in your life on social media. And. One thing. That really helped me. Is the realization that I do not want to control other people’s reactions. I couldn’t. But also. I don’t want to, I, I, I don’t want to I don’t want to be playing that particular game. It was really profound. Just a few moments ago, you reminded me that as a little kid, I had to use my smarts in order to survive. So the one of the very first things we talked about being in the barn, having an ear out for my dad’s boots on the gravel, I had to be highly intelligent and suss out how I could do a quick change or, you know, run the tire to the other entrance of the barn and make it out. You know, I had to use, let alone sussing out my parent’s moods and being intelligent enough to navigate around all of that and not get in trouble like we talked about. But then you grow up. And that intelligence that I used to survive. Has nothing to say. About love. Has nothing to say about being vulnerable with a partner has nothing to say about death loss. The intelligence I needed to survive is really not. Helpful in so many areas that we call human lives.

Jonathan Fields: [00:57:26] Yeah. And at the same time, right, the almost always bundled with that intelligence is a devotion, often unwittingly, but out of survival to hypervigilance. Yes. And the psychic weight of sustained hypervigilance year after year after year becomes brutalizing. And at some point, if on the one hand, if you’re perpetually in environments and communities where you feel like it must be there for me to literally physically survive, it’s something that maybe, you know, like you, you say this is a part of the equation of the life that I’m choosing to live. But but what if you could figure out a way to be in communities and conversations and in a, in an emotional and psychological and cognitive space where you didn’t feel like you needed to carry that burden, maybe not completely let it go, but not at that level. Like what would become available to you from a bandwidth standpoint for love, for connection, for devotion, for whatever it may be when you’re not carrying that, the volume of that load anymore.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:58:38] It’s such a good question. I was shocked when gajillion percent shocked when I learned that there are people in the world who are not part of communities and constantly trying to prove to that community that they’re valuable.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:51] Mhm.

Jeffrey Marsh: [00:58:53] [laughing] Uh, they’re just, you know, are part of a community and don’t even think about it. It’s like, wait a minute I want that. So yeah it’s a really, really good important question.

Jonathan Fields: [00:59:04] Yeah. And it starts to bring and bring it full circle also. Um, one of the last things that you talk about in your book, and I’ve heard you talk about elsewhere, is this notion of being passive in your own happiness is deadly, of not sitting back and waiting for things to happen, of really being active in the exploration of how you want your life to show up. And I think that’s such a powerful invitation for anybody. And it almost everything that we’re talking about, probably everything that we’re talking about, like a lot of the context has been and you’re like in your life has been in the context of gender, has been in the context of sexuality. But the truth is, just like you just described, everybody has existed at some point in a community or wanted to be accepted by a group or a person or a community where they felt like they had to, in some way hide or be someone else, or carry a different identity and give up, you know, a certain amount of their agency in the quest to just. Leave a good life to be happy. So your invitation, you know, in all the work that you do, I think it’s so interesting that literally everything that you say, every idea that you have is relevant in every person’s life, in every context.

Jeffrey Marsh: [01:00:21] [laughing] Oh, good.

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:23] That’s my global proclamation. I’ve, um.

Jeffrey Marsh: [01:00:29] Well, that’s funny. I thought you were going to, um. I don’t know if you know the LGBTQ phrase ‘to read someone’?

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:35] No.

Jeffrey Marsh: [01:00:35] You know, like, open them, book, open them like a book and read them. And, um, I really thought you I think you did pretty well. You read me. What I am is a walking metaphor. I hope it’s darn clear what I was told is wrong with me. And I hope it’s also darn clear that I love that. I love that about myself. I celebrate it, I show it, I dance within it and have joy all around it. You can do the same.

Jonathan Fields: [01:01:06] That feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. So hanging out in this container Good Life Project. If I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Jeffrey Marsh: [01:01:18] To talk well and often and kindly to yourself.

Jonathan Fields: [01:01:27] Hmm. Thank you.

Jonathan Fields: [01:01:30] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode Safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Tristan Reese about living and advocating for your truth. You’ll find a link to Tristan’s episode in the show. Notes. This episode of Good Life Project. was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and Me. Jonathan Fields Editing help By Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project. in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor, a seven-second favor, and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields, signing off for Good Life Project.