So many of us have had the fantasy of leaving behind some kind of mainstream, corporate job to follow a passion, like art, writing, or some other creative pursuit. Then, reality sets in, or rather, our belief about how impossible it’d be to support ourselves, let alone truly thrive, love what we do, and earn a great living.Which is why I’m so excited to share executive-turned fulltime and flourishing poet, Joy Sullivan and her amazing story, with you.

So many of us have had the fantasy of leaving behind some kind of mainstream, corporate job to follow a passion, like art, writing, or some other creative pursuit. Then, reality sets in, or rather, our belief about how impossible it’d be to support ourselves, let alone truly thrive, love what we do, and earn a great living.Which is why I’m so excited to share executive-turned fulltime and flourishing poet, Joy Sullivan and her amazing story, with you.

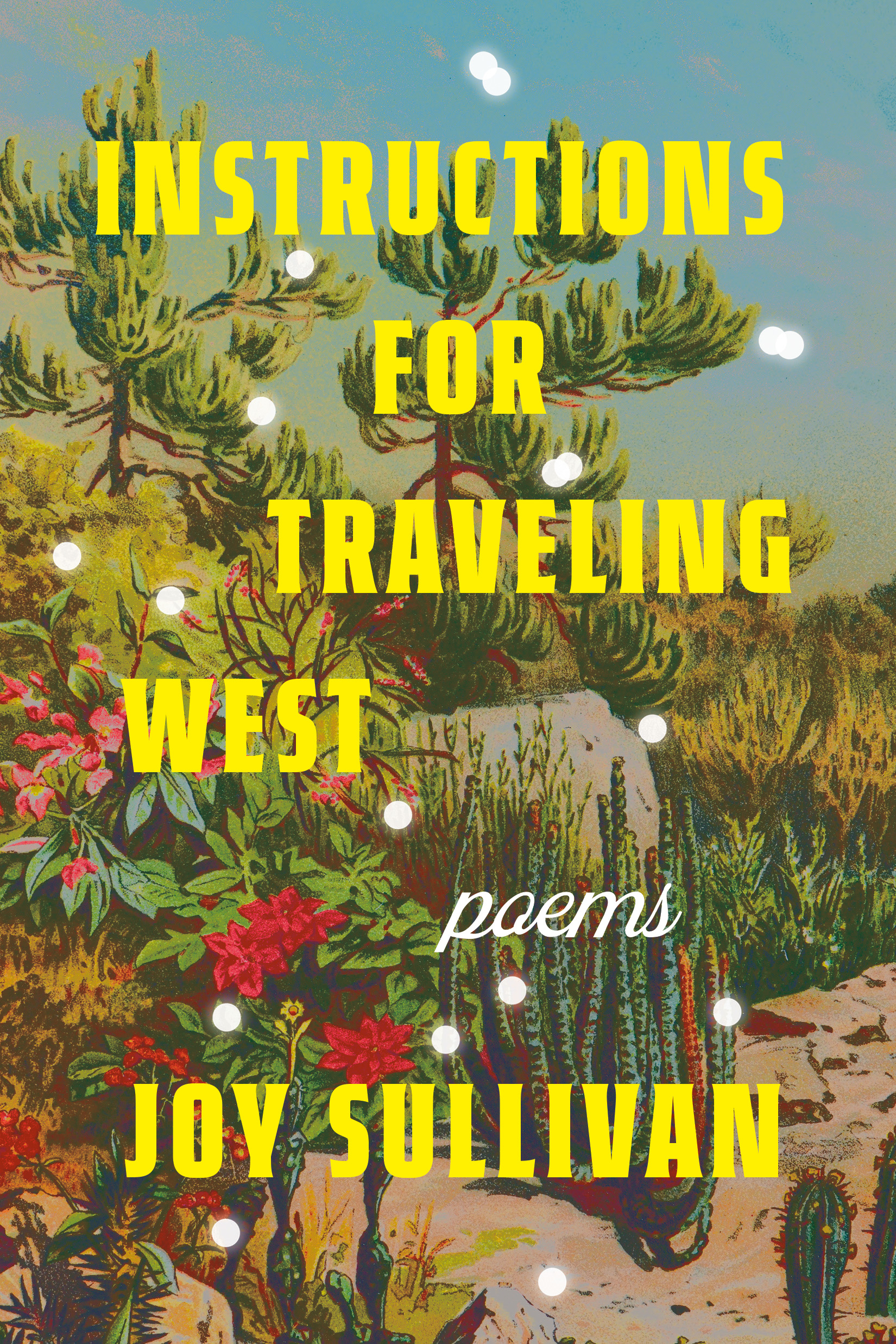

Joy went from an accomplished marketing career to becoming a full-time creative entrepreneur. In her new book, Instructions for Traveling West, she chronicles her journey—both literal and metaphorical—from the corporate world to self-expression and more-than-corporate-level living, through art.

Joy received an MA in poetry from Miami University and has served as the poet-in-residence for the Wexner Center for the Arts. She’s brought her words to classrooms and events across the country. Now, she helps other writers nourish their craft through her community, Sustenance.

I was blown away by Joy’s courage to leave corporate life behind and build a career around her creative calling. But she’s quick to bust the myth that you have to be broke, lonely and suffering to be an artist. Her story shows it’s possible to transition gradually—through a portfolio approach—without losing everything you hold dear.

Joy and I explored what it takes to overcome doubt, nurture your inner light, and manifest the life you’ve been dreaming of. If you’ve ever longed to make your passion your profession, this conversation will open your heart and mind to the possibility. Be ready to be moved and inspired.

You can find Joy at: Website | Instagram

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Morgan Harper Nichols about her journey as a successful poet and artist.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- My New Book Sparked

- My New Podcast SPARKED. To submit your “moment & question” for consideration to be on the show go to sparketype.com/submit.

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Karen Pride

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Joy Sullivan: [00:00:00] It’s a terrifying thing when the heart starts to howl in any capacity, whether in grief or joy. But I think it’s sort of a terrifying, primal feeling that sometimes when we get too happy, we get really worried that it’s going to go away. But I just was so surprised, after years and years of not literally not feeding myself great food, not eating enough, not giving myself enough pleasure, enough joy, enough freedom. When you finally give that there can, you know, enter in the sort of howling that is both grief and joy that you waited so long to start feeding the self.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:41] So many of us have had this fantasy of leaving behind some kind of mainstream corporate job to follow our passion, like art or writing or some other creative pursuit. And then reality sets in. Or rather, our belief about how impossible it would be to support ourselves, let alone truly thrive and love what we do and earn a great living doing. The thing that lights us up following some inner creative impulse. Which is why I am so excited to share executive turned full-time and flourishing poet Joy Sullivan and her amazing story with you today. So Joy went from an accomplished marketing career to becoming a full-time creative entrepreneur. In her new book, instructions for Traveling West, she chronicles this journey both literal and metaphorical, from the corporate world to self-expression and more than corporate-level living through art. Joy received an Ma in poetry from Miami University, and has served as a poet in residence for Wexner Center for the Arts. She’s brought her words to classrooms and events across the country, and now she helps other writers nourish their craft through her community sustenance. I was blown away by Joy’s courage to leave the corporate life behind and build a career around her creative calling and her deep and enduring passion for poetry. But she’s quick to also bust the myth that you have to be broke, lonely or suffering to be an artist. Her story shows that it is possible to transition gradually, thoughtfully, through a portfolio approach, without losing everything you hold dear. During the conversation, we explore what it takes to overcome doubt and nurture your inner light and manifest the life that you have been dreaming of. If you have ever longed to make your passion your profession. This conversation will open your heart and mind to the possibility. So be ready to be moved and inspired. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:40] What I’d love to do is actually start out before we even to dive into the new book and some of the poems and some of the ideas and the concepts and the stories. I also want to sort of take a broader look, because the journey that you have traveled over the last chunk of years is pretty astonishing, and some of it is, is laid out in verse in the book, but also you’ve written about it as well on Substack in different places. Two posts really jumped out at me that you shared last September, where you kind of did this two-part thing that started with lessons from leaving corporate America and then from corporate America to creative entrepreneurship. And I think the ideas in those essays would be so interesting to so many of our listeners, because I think so many people harbor these desires to make a meaningful change in the way they’re contributing to the world, to their lives and and with a really deep and profound creative impulse. But they either don’t believe it’s possible or they don’t have any idea how to do it. So you shared these two posts that I thought just teed it up beautifully. The first was lessons from Leaving Corporate America, where you kind of listed out these five different things, and you basically said, if this is what’s going on, you’re kind of like, we need to talk because this is not true. Um, could we walk through some of that? I’ll t some of them up. And I just love to hear your thoughts.

Joy Sullivan: [00:03:57] Absolutely. I’d love to chat about it.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:59] Awesome. So out of the gate, you basically write. If it costs you sunshine, relationships or health, your salary is irrelevant. Take me deeper into this.

Joy Sullivan: [00:04:09] Yeah, so I really started thinking about that about halfway through my corporate career trajectory. I had been working at a branding agency. I had worked really hard to get promoted, and for a long time that was what I just sort of thought I had arrived. The ceiling for me was going to be how far I could get promoted into this agency. And it was it was a great agency in many ways, women-owned, etc. but what I discovered in the pandemic, for me, really the gift of all that solitude. And if you’re somebody who’s in corporate America, like the first time, maybe getting to work remote in a while was this, like expansive opportunity to be outside in ways that I had never had. And it sounds really fundamental and basic, but just like the life-giving opportunity to go for a walk when I wanted to, I was like, this is revolutionary. Like, why have I waited so long? Like I’ve been so focused on my metrics have been, you know what, how far can I get in a career? And it started to take this just tremendous toll on my body.

Joy Sullivan: [00:05:14] So I had a big wake-up call when I discovered that I was having issues with my hands and with my arms from constant typing. And I went to the surgeon and he said, you got to find a different way to live or you’re going to lose your ability to write. And it was just this kind of terrifying moment that in all the metrics of my life, if I didn’t have access to sunlight, if I didn’t have access to health, and if I didn’t have access to stable relationships, for me it just all added up to net loss. So I think I am offering readers just a different way of framing success when we think about like God, is this actually, when I look at my at the end of the day, am I happier? I usually am not. If I can’t, if I’m in a job that doesn’t even allow me to go outside when I need to, or starting to really drain my body, or I can’t feel like I can have consistent relationships.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:08] Yeah, I mean, it’s interesting to me also because granted, this came when there was a forced shift. Basically everybody had to go through. But for so many, when we come to this awakening, we come to it on our knees in some way, shape or form, like we have. We’ve known it. We’ve kind of sensed it, we’ve felt it, but we’ve kind of like put it over there and then something, something major happens, whether it’s a health crisis or some other loss or, you know, a job blows up. And then we start to think about these things. And you came to this through a subtler path. But it was also it sounds like, you know, this was just a profound insight and said, okay, I can’t not do something about this anymore. One of the other things that you talk about in that post was this notion of work not making you quote good, which I think is a really interesting thing that we tend to hold on to.

Joy Sullivan: [00:06:54] Yeah. And just this idea of, like, if I work, if I get promoted, then someone who isn’t me will validate me. And for me, so much of coming back in the pandemic was this idea of sovereignty of self. Just like that same notion of like, how do I really measure success for myself? What is my body that’s telling me that I need to do or to change? It’s that same notion of like, no matter how hard you work, corporate America is not going to love you back. You are always going to be outsourcing time, relationships, and health for this thing that at the end of the day, didn’t add up to be very meaningful to me. And I think we just a lot of, you know, I grew up in a very like authoritarian culture, religious. Culture. And so for me, this idea of other people sort of either making decisions for me or also validating my worth was really hard to let go of. And I see that a lot in people and in corporate relationships that it’s like, if everybody around me is pleased with me, then it doesn’t matter if I’m pleased with me. And so I think the inversion for me of the pandemic with so many people was waking up to like, hey, I’m halfway through life. And is it adding up to something that in the end I think is really meaningful?

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:12] Yeah, that makes so much sense. And so many people have felt that and also ties into sort of like the third point that you drop around, like the importance of having a point of view, because I think so often when we step into a career, we either don’t have a point of view or we do, but we feel like we are not entitled to share it and we hide it, and we just. And we think everyone else around the table is smarter than us, you know, like more experienced than us. And listen to all the brilliant things that they’re saying. And then we kind of learn along the way that, no, actually, like that little thing inside of me is is equally valuable, which also brings it around to the fourth point in that post, which is it’s all bullshit. I feel like those two tie together really well. Totally.

Joy Sullivan: [00:08:52] They’re kind of like opposite parts of the same coin, right? I just remember my friend, I was so intimidated. I had been a teacher, I had a master’s in poetry, and then I made this career jump to go into corporate America and become like a marketer and branding copywriter. And I just remember like a huge imposter syndrome, which now I work with creatives all the time. And I just seen that this is the characteristic thing that we all struggle with. We all think our work is terrible. We all think that we don’t deserve to have an opinion on things. We all think that there’s some kind of like arrogance or narcissism present. If we have like a really formed idea about what we think is a is a great piece of art or what makes a great poem. And so for me, it was recognizing that everyone around me in this period of agency felt the same way and had these kinds of anxiety. And the most valuable thing was me, again, with that sovereignty of self, to have a point of view around my art and to say, this is the reason why I think it’s valuable in the world. And here’s the rationale that got me there. And then also to recognize that in the end, it’s all kind of bullshit. Like everybody’s on that same spectrum of trying to figure out how to be a human, how to be a good human, and how to make art that matters, you know?

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:07] Yeah. So let me ask you the question. Then. Let’s say you create something, whether you’re an artist, a writer, whatever, like a founder, you put something out into the world and there’s a voice in you that’s saying, maybe for the first time, oh, this is really good. Like, this is game-changing. Like good. Maybe just for my game, but whatever it is, how do we know without relying on others to, quote, validate it because they see the value in it and also whether it truly is what we dream of it being or whether it, you know, it’s it’s we’re kind of deluding ourselves whether it’s sort of like ego or arrogance speaking.

Joy Sullivan: [00:10:43] Yeah, it’s an interesting question because I think for me, as someone who shares their work online a lot, you can get really stuck in being like, I think this poem is only good, or I think my art is only good if it’s popular or if it’s shared, or if it gets a bunch of likes on social. And I think it’s a trap that is new, specifically in contemporary society because of the prevalent, the way we share our art and our creativity online, that you can get instant feedback and you can start to have what I think is a misconception that everything that good art equals popular art. And that’s not always the case. And for me, I’ve really had to say, if I am settled in myself, that this is an interesting idea, if this is an authentic idea, if this is a true idea that has pleased my standards, then I can send it out into the world and I can divorce myself from the outcome. Because I don’t think what is popular is always good art, and I don’t think it should be our metric for when we share or how we share.

Joy Sullivan: [00:11:46] We’re never going to know how our art lands. We can only know how it lands in our self. Right? And so for me, it was like really raising the standards for myself. Does this scare me a little bit? Is this interesting? Have I heard this before? Am I pushing this to some new territory? Am I a little bit? Is this disgusting, this idea that I’m thinking and have I pushed it far enough is a little bit uncomfortable? If someone says my art is nice, that’s just like the most depressing thing I could think of. So for me, it became about a level of taste. And I don’t mean that in a classist or a hierarchical way. I mean, have I fulfilled for myself what I think is interesting? Have I satisfied that because I see a lot of creatives and writers putting their work out there and effort of getting more likes, getting more shares, getting kind of online approval and. They burn out because they’re not feeding their own sense of creative self. They’re not satisfying that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:45] Yeah, no, I love that. It’s kind of like the way that Rick Rubin describes, like when he senses what he likes. It’s just he’s a very developed sense of taste and he just knows it. And if it goes out into the world and people love it, awesome. That’s great, you know? But if not, he’s still there’s something in him that says like, this is the only aspiration for me is to create something that rises to my level of taste, which really brings it around to the final point in that post that we were talking about, which is to nurture your knowing, to like, you’ve got to know yourself. You can’t understand this if you don’t like what is your taste? What is the thing that that is deeply embedded in you, that you yearn to get out? And how do you know when you’re getting it out in a way that’s meaningful to you?

Joy Sullivan: [00:13:26] Totally. I’m very much about the wisdom of the body, the intuition of the body, the instinct to travel west. Animals have it too, right? This instinct to migrate that I think somehow as people, we think that we’re not just animals that also have instincts that lead us to some other path, to some other place, to some other life, which is where we really need to be. And so this idea of nurturing your knowing is like, what are those intuitive hits that we get all the time, but we kind of push down or suppress? I mean, very early on when I was working in agencies, I would see people, you know, I was I started as an intern, an unpaid intern at like I was like 28 and I was, can I intern here? I had no experience in the corporate world. And I would get these hits of like, man, I could be doing that. I could be in front of the boardroom, I could be leading the creative presentations. And and that helped me take a lot of risks in that career. And then those same intuitions, instinctive hits told me, hey, it’s time to get out.

Joy Sullivan: [00:14:28] Like your body is tired. There is more that you can do. There are leaps that you can take, but I think we have to get really quiet. And for me, that happened in the pandemic was getting quiet enough that I could actually hear what it was inside me that was asking to come out. And I went to all the middle of the desert in Arizona to do it. I mean, I really got quiet. There’s something about the desert in wintertime that’s like the most silent place on earth. And in the stillness, in that unbearable stillness, you get to hear what it is that your body is asking you to do. And sometimes you can’t even name it. Sometimes your body doesn’t even know. It’s just a thread that you know you have to pool. Like I know that I need to reframe my life. The call for me was to reframe my life and prioritize health, sunshine and relationships and deprioritize that time, promotions and money and my life totally flipped when I sort of nurtured that knowing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:29] Yeah. And I mean, it’s it’s interesting you describe the word um, like that going out into, like the quietness as unbearable. And for so many it is. And, and I almost wonder whether the unbearable part of it, for so many of us, is the fact that when we get really still, when we sort of, we eliminate all the distractions, all the stimulation, everything else, and we just said, there’s nothing but us, you know, there’s nothing. You know, that moment makes us face whatever it is that’s been brewing that we’ve kind of been setting aside. And you’re like, there’s nothing to distract me from it anymore. And that’s the unbearable part, because oftentimes those things are not things that are happy for us, and we don’t know what to do about them. You know, for you, at least in part and as part of this journey westward for you, but, you know, set in motion even earlier, it sounds like, you know, and this also kind of leads to the, the part two of the the post that you shared on your Substack. You know, it led to this really big disruption to a big transition from this, you know, corporate career that you had started out as an intern, built up your copy directory, like really succeeding by all the quote, you know, external metrics, and then you decide, no, like this is this actually can’t be my life anymore. And you leave corporate America to go into creative entrepreneurship. And in your writings you address a series of myths that I think hold a lot of people back from this. One is this myth that if you’re going to be a quote artist, well, there’s a certain amount of starving that is just embedded in that experience. So take me into this.

Joy Sullivan: [00:17:01] Yeah, I was just so surprised within the corporate creative world because it was still a creative profession, all these myths or misnomers or ways that you kind of got stuck or fixed in corporate America. It really talented, brilliant, creative people stayed in jobs where they were making less money, I think, than if they would have gone elsewhere because of this idea that, like, I can’t, I have to stay in a traditional fixed structure. I think it comes back to this like work makes me good, but then also like, I’ll never make more money than this. I own. Like I have to be tied to this structure. Artists starve. They can’t be successful. They can’t learn the art of marketing. There’s no way to promote yourself without being icky. You can’t be a best-selling author and not sell out. So there’s inherently I think creatives get it on both sides. You get it from corporate America, which is really invested in keeping you in that paradigm. Right. And the myth there is like, you’ll never make more money. You’ll never have stability like you have here. And then you also duly get it in academia and on the creative side within like MFA programs that are like, we’re actually never going to give you any money to teach.

Joy Sullivan: [00:18:20] And so you will be you will be a starving artist if you pursue that. So for me, it was sort of revolutionary to find this third path to take, like some of those skills I had learned in marketing and some are just I mean, I’m very grateful for my time in corporate America because it taught me a lot about how to market, how to promote, but also that resolve of remaining authentic to my own taste, to my own sovereignty as an artist, that there really could be a very happy medium between those two things, and the idea that you can’t make as much money doing your own thing as an entrepreneur was so happily overturned for me. You know, I started my own writing community, and to be able to work for myself, doing the things that I wanted to do, I had just such a different level of investment. And pretty soon I also saw a financial return that was was pretty exciting.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:13] Yeah, it’s not that when you, you know, I’m many decades into my life as an entrepreneur in many different versions and iterations, and you certainly don’t work less. You know, also in a very past life, I had a hot minute in the context of my life as a lawyer, and at one point I was working in one of the largest law firms in New York City, and I often work more hours now, even though I worked a lot of hours back then, and I would complain about the hours that I worked and how I had no life and it was ruining me and my health and all this stuff and my relationships. I work a lot of hours now, and I always have, but it’s a completely different context. It changes the way you feel when you know it’s more of an expression of something as deeply meaningful to you. It matters to you. It’s an expression. It’s like an emanation of who you are. And I think one of the mythologies and you kind of speak to this is it’s not the hours, it’s the context that wraps around those hours that makes them like potentially so grueling and depleting.

Joy Sullivan: [00:20:07] Totally. I think, as humans, again, for me, it was really revealed in the pandemic was this idea that we’re built for meaning. And I don’t think anything is as harmful to our health as doing work that we perceive as meaningless. And it’s not to knock on people who are in different careers than the entrepreneurial path that I have landed in. But I couldn’t think at that point in my life, in the middle of the pandemic, anything less meaningful than developing email campaigns, right, to sell products that I just didn’t think mattered. And so for me, it is to your point, it’s not only a question of restructuring in your life towards like our ultimate value system, but it’s also about like finding meaning and purpose. And so for me, it was a realignment with like, what do I think that really matters? And for me, that has become helping people find their true, true, their voice. Right. That is work that felt like the work with the capital W. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:08] Brings up another point that you mentioned, and this is one of the other myths, which is that if you do creative work, you’ll automatically love your life. That’s not entirely true. Also.

Joy Sullivan: [00:21:18] Yeah, that’s such a funny one because, you know, now I am a full-time writer. I’m that mysterious unicorn that people are always like, oh my God, you’re a full-time writer. They don’t even ask me questions. They just say, God, you love that, right? And it’s kind of like not all the time. And the hard part of being a full-time writer, even though I feel often very aligned to that purpose, is like suddenly you’re responsible for your timetable. You are responsible for a lot of other things. As an entrepreneur, you have to hire people. You have to run a business God, you have to do taxes, which is just like the worst thing in the entire world. So it’s not always like flip the switch and you’re automatically going to love everything about your life. I think for me, it was recognizing that there’s a real trade-off in this new realm, and that like having full-time access to writing was sometimes its own kind of burden. Like to make what you love the art you make, take on all the pressure of your happiness is a lot to ask.

Joy Sullivan: [00:22:20] I think about it in comparison to someone that I worked with at my agency, and he was a musician and an artist, and he refused promotions consistently at this agency that we worked at. And instead he just said, like, I want to come in, I want to work eight hours a day, and then I want to go home, and I want to make art and I want to write music. And that also occurred to me as like a very valid path forward to say, like, I’m going to put my time in here and then I’m going to go home and I’m going to make art. And he wasn’t asking his art to support him or to become his entire financial means. Right. So I ask people when they’re thinking about these things to really consider, like, what is the role that you want art to play, and are you ready for it to try and support you financially and emotionally? Sometimes it’s not always the payoff. Depending on who you are as a person, that’s worth doing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:15] Yeah. So agree. I don’t know if you’ve ever read the book Daily Rituals, but it basically tracks the 24-hour, sort of like daily cycle of so many different people, writers, artists who are iconic are really well known. And when you read that, it’s amazing to see that a number of them had full-time jobs with no intention of ever leaving those full-time jobs. They were kind of mundane, but they were. They were okay, and they took care of the expenses. They took care of the family. They took care of. They took that off the table so that when they went and did their art on the 5 to 9 and then on their weekends, it gave them the freedom to not have to worry about whether this art was rising to the standard of being sellable. It was just an expression of what they wanted to create, and that led them to not censor totally in a way that actually let the work be the work. And that in turn ended up making, you know, like an astonishing impact.

Joy Sullivan: [00:24:10] Truly, I think there’s such a myth. I should have written this as a sex myth in this article. But there is such, this myth that when I have, you know, I’ll make art when I have more time, or God, if I could just be a full-time writer and have that literally be my job to get up and write, then I would make art all the time. I’d have a novel in no time. I would have a collection of poems, whatever it is. And the reality is, often when you have to change your relationship with art, like when that thing gets to be the art you get to make, at the end of the day, it changes your relationship with it. You’re really excited. You want to do it, you’re making time for it. And you know, I have never been as prolific, honestly, as when I was writing between work calls and creative presentations and on my lunch break, because I knew I have seven minutes, I’m going to write now when I wake up and I have two hours to sit at my desk, I don’t feel pressured in the same way. So I always tell people, just collect the scraps. If you’re somebody who’s never going to leave a 9 to 5 job, if that’s working for you, and also if that turns off sort of the part of your brain that has to be anxious about money and all those other things, then that’s great for your art, but just collect the scraps. I think people underestimate the amount of time you can actually dedicate to writing if you write in the five-minute in-betweens.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:32] Yeah, so agree. And so often I think the snippets, the ideas, like the sentence fragments that become amazing things down the road, you’re doing something entirely differently. And it just it drops into your head and you’re like, ooh, I have no idea what this is, but I need to write this sentence down because at some point it’s going to become something. So, so much of it just happens in those in-between moments.

Joy Sullivan: [00:25:53] Totally. And also the myth of like, I have to have the cabin in the woods, you know, and my whiskey on the desk and my, you know, cigarette with the long holder. And then I’m going to be this great American novelist. Right. And that’s not how the. Majority of writers that I know and myself. It’s just not how we produce work. It’s a really unsexy ways for me. Sometimes it’s literally first thing in the morning before I’ve got an interview or before I’ve got a meeting or a work call. I have ten minutes in my laptop in bed that I’m dashing off. The first thing that I come to and like that doesn’t feel like the sexiest piece of advice, but I think we have a misnomer that hurts people. You have to go to a cabin in the woods, or you have to have immense amounts of time, and I just don’t think that’s how brains develop creative work.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:42] Yeah. I’m curious about your take on, on on a different thing that I’ve heard a lot. Also not necessarily in the context of writing, although certainly in that context, but in the context of quote creating great art. And and it goes the refrain goes something like this in order to create great art or great art comes from great suffering. When I was a kid, when I was on my late teens, I remember spending a summer out renting a house and painting houses on the east end of Long Island and like, kicking around in bare feet. And and my roommate in that house was an aspiring writer. You know, he’s probably 20 years old. And at one point during the summer, he vanished and basically said, I need to. He lived a very privileged life. He came from a lot of money, but he wanted to be a great writer. And he basically said, I need to suffer in order to be a great. All of the greats have suffered like mightily. So, you know, he basically took a backpack full of clothes, bought up an old beat-up station wagon and drove out to the middle of the country and said, I just need to live, you know, like in a really tough circumstance. Forget the fact that there was great privilege, that still waited any time, you know, he wanted to turn back to it. But what is your take? And I have heard some artists who have created astonishing works say like it came from suffering, and they were literally afraid to remove suffering from their lives because they were afraid it would no longer allow them to create the work that they want to create.

Joy Sullivan: [00:28:06] Yeah, it’s such a fascinating topic, and it’s one I’ve thought a lot about because for me, yes, I think suffering is helpful because suffering does bring us to language. It drives us from it. Literally suffering drives language from our bodies. It sometimes until we are in I mean, in any change that we make, it’s usually suffering. We get uncomfortable enough to have to make it. But I don’t know that that exactly is the prerequisite. Like I think for me it’s not necessarily suffering, but it’s the ability to inhabit lives that are not necessarily my own. And what I mean by that is the gift of like, moving west. Was this just tremendous ability to be anonymous for a while to, like, enter a new city. I could go into the bar and say my name was Ada and bring my typewriter if I wanted to write it. Was this totally this ability to find a multitude of things that I wanted to write about and people that I potentially wanted to become. And so I think there’s a level of discomfort of like really saying like, what is it inside me? And I think suffering is one modality, but I think there’s many ways to get there. As an artist, I’m not really a fan of this idea that we have to live in perpetual states of melancholia, which are often hurt our art as well, because they can be hand in hand with things like depression or unhealthy patterns of relationships that sometimes, like accompany our depression. And so I want to release artists from this idea that they have to be miserable. But I do think to be a good writer, you have to be willing to be uncomfortable.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:46] Yeah. And maybe even if, you know, you don’t have that suffering in your own life to cultivate empathy so that you can understand what’s going on around you and really sort of like feel into other people’s experiences.

Joy Sullivan: [00:29:59] Truly.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:00] I want to kind of put a bow on this part of the journey, like because people may be thinking, okay, this sounds really interesting. I’m inspired, like there’s a whole bunch of myth-busting, but she literally went from corporate America to creative entrepreneur. Like, what did that actually look like? And for you, you listed this out. You know, first it was part-time, like pulling back to some part-time work in the agency. So you had a little bit more bandwidth to then start to devote to the next thing. Then you started typing live poems, like at different events or parties or whatever it is, and getting paid for that. And by the way, I have seen a number of different people doing this at events. It’s a real thing. Um, yeah. And then getting commissioned to write poetry online to create and then creating prints and then running workshops and then eventually creating your own community sustenance community to support other writers. And that it’s like the portfolio of these things that eventually culminated in you saying, okay, so I can literally step into this and do the thing that I want to do. It wasn’t like I just you snapped your fingers and you’re like, okay, I’m a poet. Like I was a copywriter, like focusing on branding and marketing, and now I’m a poet and everything’s awesome. This was a process. And there were a number of different things that you did to piece together and then eventually kind of figure out what form and shape does this do people want to actually support financially and will give me those things that I said I held dear and like the sunshine and the relationships, did I miss anything there? Is there a context that makes sense to add?

Joy Sullivan: [00:31:26] No, I think that’s exactly right. I think, again, people think like, well, God, I have to just jump straight into the abyss without having any plan. And there can be a strategy to that, because when you’re free falling, nothing motivates you to get your life in order, like the immediacy of having to, you know, figure out rent. But I didn’t go that route. I definitely took it piece by piece, step by step. And my agency was very kind and letting me go part-time. But that allowed me to open up okay. If I can spend two hours a day now on writing or writing-related things, what does that open for me? And I sort of built this path forward very slowly. I’m actually a risk-averse person, and I have had to build a lot of courage around making these leaps. And, you know, I sit at my writing desk every day and I have all these trees overlooking my street here in Portland, and I watched the squirrels leap from branch to branch to powerline to the rooftop. And I got really interested in how does the squirrel know? Like they never fall. How do they know the distance between the power line and the branch at the top of the tree? And so I actually did a little research on squirrels and how they learn to judge their leaps. And it’s that they take very small leaps at first, and then they slowly build to these longer, really astounding leaps. And when they miss a branch, they have these claws that can cut and they can also like somersault back. They’re like incredibly agile creatures, but they basically take all the data from the mis-leaps and they apply it to the new leap.

Joy Sullivan: [00:33:10] And I thought, God, this is a metaphor for leaving one’s life and the ways that we teach ourselves as humans to leap like the reason squirrels don’t fall is because they have. If they miss, then they have claws that are going to catch them on the way down, or they can course correct mid-air if they’ve overshot, and then they get to apply all that data to the next leap. So for me, I took just a small series of hops, you know, going to part-time moving to typing poems live, which is its own kind of tear. Right? But really reinforces, like, hey, I have the skills to recover. If I overshoot, I can think quickly on my feet. I can bang out a poem in five, you know, 5 to 12 seconds in front of a stranger if I have to, at a live typewriting event. And then from that, you know, proving to myself, okay, people will now pay me for that, will they pay me to commission poems? Okay. I proved to myself for that. Maybe I could start posting poems online. Maybe I could start a Substack. So I think sometimes as creatures and as human animals, we’ve got to almost teach ourselves the science of the leap and build our own courage. We have this idea that we’re trying to prove to the world that we’re an artist, but I think, firstly, we’re actually trying to prove to ourselves that we’re an artist. And a lot of that evidence building, it’s just the science of the leap is figuring out, okay, I’ve done this far. Can I stretch, can I jump a little further?

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:34] Mhm. I love that the notion that we’re really trying to prove it to ourselves first, you know. Yeah. And what I’m hearing also is that somebody needs to write a book called The Squirrels Guide to Career Change.

Joy Sullivan: [00:34:44] I know! Right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:45] Haha

Joy Sullivan: [00:34:45] Because it’s like they’ve actually done all this research on squirrels and doing parkour. And it’s like, we got to apply this.

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:53] That is awesome. That now I’m like, going to have to go research squirrels because now I’m really curious about this. It kind of leads us to your instructions for traveling west, you know, and this is words and thoughts around both a metaphorical and a literal journey that really has unfolded over the last chunk of years. What leads you to decide to sort of like, mount this journey and then document it and share it?

Joy Sullivan: [00:35:16] Yeah. So again, when I was, you know, in the middle of the desert in the pandemic, I wrote this poem to myself, and it was me trying to believe in myself as a writer, as a woman, as a solo traveler. At that time, I had done something. Again, it goes back to the idea of making yourself really uncomfortable. I’d done something really scary for me, which was to travel for six weeks across the American West by myself. I had never really traveled alone before, and so in that process, I wrote this poem called instructions for Traveling West. And it was it begins, you know, first you must realize you’re homesick for all the lives you are not living. I always tell people, be a poet, not a preacher. I was not preaching to other people. I was telling myself like, Joy, there’s something inside you that is asking for. A different life and has been asking for a long time. And then the rest of that poem was literally just all the things I wanted to say to myself, you know, give grief her own lullaby, Knight yourself with all your newborn courage.

Joy Sullivan: [00:36:22] And I think the beautiful thing about the page and about poetry is it has this strange alchemy. When you take a leap on the page, you can take a leap in your life, right? You sort of practice that idea and the safe space of the page. And within 40 days of writing that poem, I had sold my house. I had packed up my Subaru, my two cats, and all my books, and I’d left a relationship and I had gone part-time at work. And so it was just this kind of amazing momentum, I think, both within poetry and with also within. Really getting clear on yourself was what is the thing I need to say. And if I really make good on that, how does my life transform? And then I just remember posting that poem and being shocked at how many people resonated with this idea of traveling west, you know, physically or as a metaphor for their life. What was the thing that they were kind of not looking at or looking away from? And what was their figurative west?

Jonathan Fields: [00:37:27] Yeah, I could see so many people really just embracing that. It’s funny as you’re describing it. Also, after I was a lifelong New Yorker, like raised a family, married like in 30 years in New York City. And September 2020, in scariest part of the pandemic in New York City, you know, we packed up and came out to Boulder, Colorado, for what we thought would be a couple of months, three and a half years later, as we’re having this conversation, like, now, Boulder is home. And there’s I think so many people launched into this journey. But I love the fact that the notion that something can start on the page and then somehow become real enough that it inspires you to manifest it, to actualize it. But then, you know, a part of that sort of like that poem also, you know, like the lines also come in that you must commit to the road and the rising loneliness. And I think this is something that sometimes we’re fearful of because we feel like if we’re leaving all of these things behind, what lies ahead of us is not just possibility, but also loneliness. Because we don’t know the people, we don’t know the places, we don’t know what’s going to happen. And a lot of people from our past lives won’t understand what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. And I feel like this is so much of what you weave into the different writing in this book.

Joy Sullivan: [00:38:48] This idea that, like, you always have to go and that if you go, if you take the leap, your life will just be great. You know, everything will work out for you. You’ll find your your true love. You’ll find your true career. You’ll find your true home. You know, there was a part of me that really wanted that to be true. When I started this journey, I was like, I’m going to do one scary thing, and then the rest of my life is just going to be great, and then I’ll never have to do anything again. And what I realized is like, God, this road comes with its own price. It is hard. It is hard to leave a life. There’s real grief. There’s real loss, there’s real loneliness tied to that. When I was writing this book, I had all of my poems laid out, and I have organized the book into sections that are different lines of that initial title poem. And I was trying to end. I realized that I was writing the poems towards this idea of home as the ending. I wanted the last section of the book to be home, and I could not finish that book with that structure. And I realized that I was also trying to live my life with this very singular.

Joy Sullivan: [00:40:07] Okay, I’ve done the one scary thing. I’ve been lonely. I’ve experienced loss. I’ve reinvented myself. I get to stop. And I realized that that was actually wasn’t a true it wasn’t a truth for me. I hadn’t lived it. And for me, I had not found home at the end of this book. I haven’t found every answer to everything, but I have found this tremendous sense of self and this tremendous sense and confidence in the ability to continue to leap, which is inherently uncomfortable. But it made me rearrange the order of the book, as you know, lines of that poem. And so the book now ends with the section Joy is not a trick, but it doesn’t end in home, because for me, that was a falsehood. And I didn’t want to write a book that wasn’t true. That felt like the worst death in the world. To hand you some kind of satire, an idea that if you leap once, it’ll all be okay. The truth is, we don’t know. It might not be. But I’m trying to suggest to readers it’s absolutely thrilling and absolutely beautiful and absolutely profound to still take the leap.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:15] Yeah. And once you hit on the reality that actually my current state is not okay, then you’re not comparing some false illusion of okayness now to some uncertain future once you realize, like, actually, you know, things aren’t as they seem now. So yes, I’m stepping into uncertainty, but also possibility. And maybe that’s better, you know? In one of the early poems. Remember what it was like to be a kid? You really sort of, like, recount childhood wonder in that state of wonder. Do you find yourself dipping back into sort of like intentionally moving back into that childhood state of wonder, especially as part of the sort of the creative or the writing process?

Joy Sullivan: [00:41:58] Um hmm. That’s a beautiful question, Jonathan. I’ve not I’ve never been asked that. And I quite like that, that framing I do, because one of the best pieces of advice I was ever given as a writer comes from Brendan Constantine, a poet, and he talks about, like, moving through the world as an alien. You’re seeing everything for the first time, and that is what it is to be a kid. You’re just this little tiny alien on Earth, and you’ve never seen any of this before, and the kind of immense wonder. And so when we think about writing beautiful, profound, life-changing work, it comes from that sense of sort of isolating or defamiliarizing oneself from the world. And it’s a whole like philosophy of detachment or defamiliarization in art. It’s a sort of better see it, right? Picasso deconstructed the face so that you could better understand what it was to be human. And I think that that’s really important in our work. Like, how can you see the world for the first time? And a lot of times that sets a child. And for me, that was seeing the world and then learning language for the world was so fundamentally powerful for me.

Joy Sullivan: [00:43:14] And I’ll just tell this brief story. I remember as a kid we lived in Central African Republic, so we lived overseas. My dad was a doctor and we had a telescope set up in the backyard some nights. And when we would look out and we’d see the stars, and there was a man from a neighboring village who came by the house and wanted to look out the telescope. And he had never seen the sky up close before. And as a kid, seeing that man, its face, the jubilance that came over him to see stars up close and the moon up close, I thought, God, if I could have one ounce of that in my adult life. Now, when I think back on his face like that is, the joy of being alive is to see things fresh and for the first time. And I think that’s the gift of poetry, is we get to do that over and over. We get to sort of relive that sense of childhood wonder.

Jonathan Fields: [00:44:04] I mean, do you feel like that is an inherent in poetry, or do you feel like that’s the lens that you deliberately bring to the way that you write poetry?

Joy Sullivan: [00:44:12] I think both and I mean, I think good poetry asks not to just be read, but to be felt in the reader’s body. And the only way I know to get you to feel something in your belly and not your brain, is to ask you to experience it for yourself. So you have to use that defamiliarization technique. You have to say it in a new way. You have to say it as if you were a child seeing it for the first time, or else. I think we bring all our own preconceived notions, memories, ideas to that thing, and we don’t get to experience it in its fullness. So for me, also, having been a stranger in many places in my life growing up overseas, moving back to the US when I was young, I’m kind of used to that strangeness of a new place and seeing something as if I were seeing it for the first time. So I do try and apply that to my work. Like, what if I was experiencing this and I sort of take myself back to those years of acculturation where the, you know, US Ohio, where we were was just blaring and strange, and there was Walmart and Happy Meals and highways so fast it felt like flying, you know, what is it to be a new creature in this world, to sort of have that alien experience? How can I translate that to the page in a way that wakes up my readers, too?

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:35] Yeah, that also ties in really beautifully to one of the later poems in this same part, roads, where you really explore the theme of belonging. So it’s interesting the notion of sort of like constantly looking with fresh eyes, beginner’s mind and and being in different places with new people and new experiences, but also trying to tap into the sense of this innate human need that we all have to feel a sense of belonging. And I wonder whether you feel like belonging more is an outside in thing or an inside out. Can you.

Joy Sullivan: [00:46:05] Say more about outside in, inside out.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:08] Whether belonging comes from those around you, seeing you as you are and accepting you, or does it first need to come from you, seeing you and accepting yourself before anyone else ever has the opportunity to do that?

Joy Sullivan: [00:46:21] Yeah, it’s such an interesting question. You know, I think for me, belonging has been this really elusive thing. Just like the every time anyone asks me where’s home, I just curl up into a ball and I don’t know how to answer because I moved around so much as a kid and I was constantly shifting culture. Right. And so, ironically, when I came to words, it was because I couldn’t speak the languages of the places that I was in. So to come to the page and sort of have this private way that I could communicate was very sacred to me. So I do think the sense of belonging for oneself has to come from that innate listening to the self, to that innate listening to the voice. I think we all like to think we’re special little creatures, for whatever reason, that, oh, I just I’ve never really felt like I’ve fit in anywhere. I’ve never really felt like I belong. And I think that’s just like a fundamental part of being human is that we always feel on the outs a little bit of any community that we’re in. But I think really what that points to is more a discomfort with self. I think when we get really clear on what that voice is, who that person is, what that sovereign self is inside us, it matters less sort of the geographical location that we’re in, or the sense of larger home ness. It can just be in oneself, if that makes sense.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:44] Yeah, no, I think that resonates with me. Further into the book, you really deepen into life’s simple joys, appreciating life’s simple joys, the deep instinctual response of the heart to true happiness. Tell me more about your take on the heart’s capacity to sort of howl for joy.

Joy Sullivan: [00:48:03] It’s a terrifying thing when the heart starts to howl in any capacity, whether in grief or joy. But I think it’s sort of a terrifying, primal feeling that sometimes when we get to happy, we get really worried that it’s going to go away. And that’s where that line comes from later in the book. Joy is not a trick. It’s like if I really let myself feel terror and then I really let myself feel joy. If I really let myself feel all of life, what happens when I don’t can’t feel it anymore? And that’s a terrifying question, right? And Maya Angelou, she was asked, can anyone write a poem? And she says, I think so. I’m not sure everyone would write a poem, but in order to write a poem, you have to have sharp ears, and you have to not be afraid of being human. And for me, that’s really the key of like, what it is to fully feel is to have the courage to fully feel it all, which is something we’re always all trying to do. But I just was so surprised, after years and years of not literally not feeding myself great food, not eating enough, not giving myself enough pleasure, enough joy, enough freedom. When you finally give that there can, you know, enter in the sort of howling that is both grief and joy that you waited so long to start feeding the self?

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:27] Yeah, no, that makes so much sense. And part of that howling I feel like is also often embedded in there is longing. And this is something that you speak to in Ghost Heart, you know, which really reflects on the longing for places and lives unexplored, that concept of sort of unfulfilled futures and the feeling of belonging to the unknown. And I think so many people relate to that sense of almost like unquantifiable or unidentifiable longing, but they just feel it in their bones in some way.

Joy Sullivan: [00:49:58] It’s so fascinating to me. And Cheryl Strayed calls that other life, that life that we’re homesick for. Her version of that is the ghost ship, right? That you sort of salute from the shore the other life that you didn’t get. But I think there is some part of that that is really natural and that we can’t change, that. We’re always going to have wistfulness and longing. It’s like that sort of discontent. It’s part of being alive. But I also think there’s such wisdom in what that longing is asking us to do. Again, if we compare it to the call that animals get to migrate instinctually, our bodies are asking us to listen to that in some way. And I think even if we can’t all leave our lives, we can’t always move west or quit our jobs. I think it behooves us to listen to the wisdom of that the body, the wisdom of longing, the wisdom of want, if you will. I just know before I left Ohio, I woke almost every single morning at 4 a.m. from the same dream, and it was that I was stuck in a barrel of water decomposing. And it was this terrifying image. And every morning I woke with that. And the day that I drove away from that little blue house on Avondale and moved to Oregon, the dream never came back. And so I think there is this idea of like, what is the body asking for? What is the life that we haven’t lived? How can we answer that? And I think it looks different for every person, but I think there’s wisdom in listening.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:33] Yeah. So agree. And you use the word dream and it shows up in different ways in your writing and in this book, you know, in the part where you. Or giving grief. Her own lullaby in one of the poems is called dream, but you sort of go dream is sort of like when you get to that place you’re talking about collective, not just collective dream, but collective grief, and you sort of ease your way into it with a, with sister, sort of like you’re talking about the different individual explorations of grief. And then you, you sort of you move your way around to this poem, block five, which is really sort of exploring. Okay. So yes, and like we all feel this individually. We feel it collectively. This is a part of the human experience. And even while we’re moving through it, we still have access to these small joys. And I think so many people struggle with that. Dear friend of mine, Cyndie Spiegel, wrote a book a couple of years ago called Micro Joys, where she was moving through a profound season of just astonishing loss and grief and sadness. And yet she found she still had this capacity to, like, find these tiniest little moments. But she almost had to let herself feel them, because so often we’re like, I should be like, there are reasons for me to be in the state of profound loss and grief. I should not be feeling joy now, and we shame ourselves when there’s a glimmer of it. And it seems like this whole part was sort of like dancing with these ideas.

Joy Sullivan: [00:52:59] Yeah, I think there’s this strange mechanism of grief is how closely it is associated with joy, and how terrified is people that we are to feel either one of those things. But I think there is this, this time when we’re experiencing loss and loneliness, the dark gift of the pandemic was it also brought into sharp focus all these things in our life that were quite beautiful. And then I think a lot of us got to the, you know, a couple years into that and didn’t want to let go of those things, like those things that came into focus as became not only small joys, but deep delights. You know, the ability to go for a walk every day just became a pleasure that I couldn’t imagine having to let go of when we were all supposed to come back into the office. Right? So for me, it was this idea of like, Ross Gay also talks about this in his, uh, Book of Delights, but just these small ways every day that we’re finding meaning and that these actually grow within our collective imaginations when we give them time. So within my writing community, I call it tiny tenders. I say that the base of every poem is a tiny tender. It’s one small detail. It’s one small thing that you have witnessed that you are now going to give reverent attention to on the page. And so I think it’s really an exercise of that reverence of attention. You know, I just remember in the loneliness of being on the road, standing in the sunlight, washing tomatoes in my sink. And I looked down and I thought, My God, I’ve never seen anything so beautiful as these tomatoes. And I never want to lose this reverence for these dumb tomatoes. But for me, it was about that, the reverence of attention that we can bring to those small delights and how we can stretch them out and give them to one another.

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:48] Yeah, that reverence and the attentiveness, I think is just so lost in so much of our lives these days. Um, you know, the pace of everything’s accelerating. We live in a state of such perpetual distraction that when you can drop into it, even for a heartbeat, you’re like, oh, this, this is actually what it’s all about. You also. And you wrap around to this in the last part of the book, you remind yourself, um, joy, not a trick. There’s a peace when the Queen dies where she’s sort of saying, let’s pay attention, let’s be here. Let’s acknowledge the loss. And also, there seems to be this underlying instinct in us to move forward. Um, so I’m curious, like in your mind, how do we navigate between this attentiveness to the moment, to often to loss, to change, and to standing in a place of, of also constant access to hope and possibility?

Joy Sullivan: [00:55:34] Yeah. It’s so interesting, just even as a woman now who’s gone through therapy a lot, and the thing that my therapist always is always talking about is this feeling, it’s like, I don’t I feel all the time, okay, I’m a poet, right? She’s like, well, Joy, I think you could still feel a little bit more. Right. And so it’s this idea of like feeling every feeling fully of like having to feel all of it, and then that getting us to the next place that we’re supposed to go. So I think that poem begins, you know, the instinct of bees and of the body is to be rebuilding. And sometimes I imagine myself and all the emotions and all the things that I feel is literal bees inside me that are just quivering forward, like they’re trying to feel the ecstasy of the grief or of the joy, and then they’re literally trying to rebuild and to find the honey and the sweetness and all those things. And there’s that line in the poem that talks about, you know, who is the first person that told you that your soul’s monarch was dead? And then even so, what did you turn into, honey? And this idea that no matter what card we’re dealt in our lives, like, what are the ways that we insist on healing? What are the ways that we insist on rebuilding? Just like bees insist on making honey? I just think there’s such a beautiful lesson in that.

Jonathan Fields: [00:56:57] Yeah. So agree. When you bring a work like this book to the world, when you’re working on it, when you’re writing it, when you’re living the stories that then end up becoming the words and end up becoming the emotions and the feeling sensation. I’m curious, do you create an intention beyond your own honesty and expression, or a desire for how you want this work to land in others minds and hearts?

Joy Sullivan: [00:57:23] The only thing harder than writing the book was living the book, right? So it’s sometimes hard when you’re a person who writes a lot of autobiographical work, a lot of poems that are clearly the I is the poet in the speaker and the writer one in the same. It’s sometimes tough to then send that book into the world, because you basically feel like you’ve invited everyone over to look inside your closet and to talk about all the house dresses that you wear. Right? So it’s this kind of bizarre feeling to feel like, God, I put all of that out into the world, and now people are going to read it and judge me. And what I found more is that poems stand as sort of mirrors to the self. Like, certainly they reveal something about me and but mostly they reveal something about you as the reader. And that’s been really helpful for me that these poems, when I release them, I think of them as birds. That’s the only way I can write, is I sort of send them off and I say, like, now you’re your own thing now. Like you’re flying away from me. They are not me anymore. So once I have written the book, I sort of release it into the world and I say, like, you are now separate and I allow people to have their own experience with the book. Like I can’t dictate how people read it, if people like it, if people see themselves or don’t see themselves. And I think that’s a healthier approach and like keeps me sane and able to keep writing, is this ability that, like, people are mostly going to find truths about themselves or not in the work, and it’s less about my experiences. It’s now about their experience with the book. Lisa. That’s what I tell myself.

Jonathan Fields: [00:59:04] Yeah, I kind of love that frame. It’s funny because I can’t remember the poem, but I remember like being in an environment where people were fiercely debating what the writer’s meaning was behind every word, every phrase, every line. And what you’re kind of saying is like, okay, so I had my own meaning when I wrote it, but once I release it out into the world, they can. You interact with it, whatever meaning, however that lands in your heart, that’s what it is. You don’t have to know. My side of the story like this is going to land in the way. Like like honor your. This goes back to the beginning of our conversation. Like, know yourself, honor your lived experience. Like what is real for you? Like that’s enough.

Joy Sullivan: [00:59:42] Truly, I think that’s such a beautiful way to put it. And like, there’s a poem in the book called When All This Ends, I’ll throw a party. And I wrote it as a poem of longing, of deep loneliness, mid-pandemic when we couldn’t touch each other, there was no vaccine yet. And it’s just like, I want to throw a party and I want to kiss everybody, and I want to get sloppy and have blackberry wine and hug and dance. And I don’t reference the pandemic explicitly in the poem. When I posted it, everybody knew. But now people read, when all this ends, I’ll throw a party. And usually people, without knowing the context that it was written in the pandemic, see it as expression of the afterlife or a way to think about losing someone after death and like what comes next. And I think that’s so deeply beautiful. And so for me, the way that we give our poems, our art or creativity, longevity, an act of generosity is to sort of remove our original intention and to say, I’m going to allow this to be whatever it is. It’s a life on its own. It’s literally a bird flying forth. I can’t dictate where it ends up. I just have to let it fly.

Jonathan Fields: [01:00:54] I love that it feels like a good place for us to come full circle in our conversation as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Joy Sullivan: [01:01:05] I think for me to live a good life feels like fully inhabiting the work that one is meant to do, which is always going to come back to voice. So it’s again getting in touch with that voice inside you and then letting that dictate what you do, what you say, where you go, where you travel, where you land. So for me, it comes back to voice and finding one’s purpose and asking those two things to be in alignment.

Jonathan Fields: [01:01:35] Mhm. Thank you. Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode Safe bet, you will also love the conversation we had with Morgan Harper Nichols about her journey as a successful poet and artist. You’ll find a link to Morgan’s episode in the show notes for this episode of Good Life Project. was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and Me. Jonathan Fields Editing help By Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project. in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor, a seven-second favor, and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields, signing off for Good Life Project.