Take Our Podcast Listener Survey!

Imagine a world where life’s greatest challenges become the catalyst for profound creativity and growth. In this stirring conversation, New York Times bestselling memoirist Suleika Jaouad shares how her battles with leukemia unlocked a path of “creative alchemy” – transforming life’s interruptions into inspiring artistic expression.

You’ll discover how Jaouad’s journaling practice, born from years of cancer treatment, evolved into the “100 day project” that birthed her viral Life, Interrupted column. When her disease returned during the pandemic, painting whimsical watercolors became her new vessel for transcending isolation.

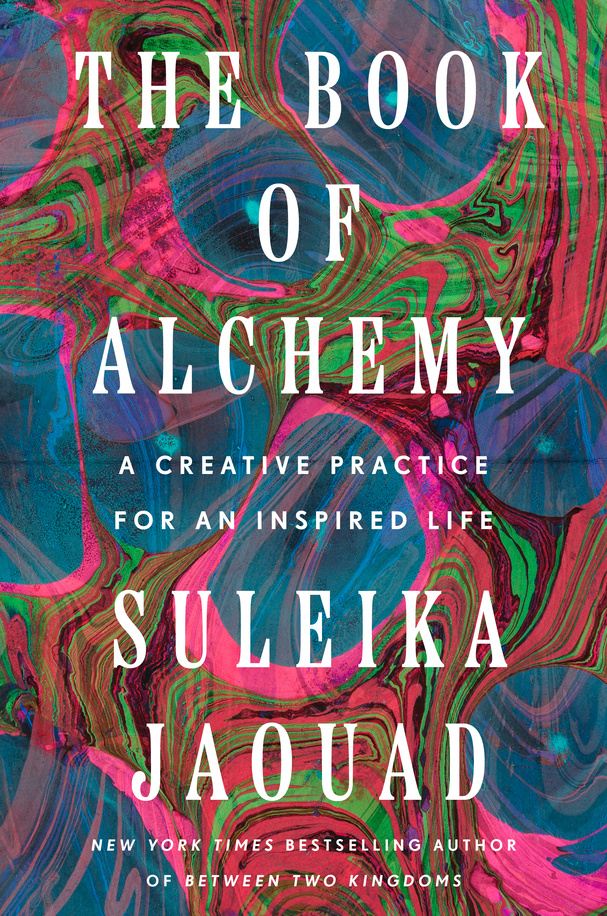

Jaouad’s journey culminates in her luminous new book, The Book of Alchemy, offering 100 eclectic writing prompts to spark your own journey of self-discovery through journaling. From Pulitzer winners to prison inmates, the prompts unearth wisdom from an extraordinary tapestry of voices.

Whether you’re navigating life’s inevitable twists or seeking to reignite your creative spark, Jaouad’s story reminds us that the alchemical act of inspired expression can illuminate even our darkest moments.

You can find Suleika at: Website | Instagram | The Isolation Journals substack | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Elizabeth Gilbert about unlocking creativity and reinventing your life.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

- Join journalist Danielle Elliot as she explores why ADHD diagnoses are surging among women in the limited-series investigative podcast, “Climbing the Walls.”

photo credit: Nadia Albano

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Suleika Jaouad: [00:00:00] None of the chemo I was doing was working. My leukemia was becoming more and more aggressive. It was terrifying and traumatizing. Within 24 hours, you know, my life completely changed.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:13] Suleika Jaouad is a New York Times best-selling memoirist and visionary creative who has found ways to alchemize interruption and struggle, including recurring bouts of leukemia, into a transformative journey of self-discovery and artistic expression. From her groundbreaking, Life Interrupted column to the creation of the Isolation Journals community and her new book on journaling, The Book of Alchemy, she empowers us to turn life’s interruptions into the alchemy of inspiration.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:00:41] Journaling, to me, felt like you know a thing you do for yourself. It’s private.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:47] You just saying, let me take the few hours I have every day to feel the way I want to feel.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:00:52] That experience had meant for me and how I wanted to apply that knowledge going forward, and even how I might navigate things differently if I got sick again. I found out in August that my leukemia is back for a third time.

Jonathan Fields: [00:01:12] You have deepened into the world of journaling and shared ideas, process prompts in a way that has inspired just stunning, stunning. Not just creative output, but community and connection at a time where I think so many people need it so deeply. Before we dive into that and the new book, which I think is so beautiful in so many different ways, I want to talk to you about a recent newsletter. You had a bit of a homecoming recently. You gave a keynote to the incoming freshmen at Skidmore, and this is a place that is not unfamiliar to you, correct?

Suleika Jaouad: [00:01:46] It has been the breeding ground of my most formative moments. Um, so, you know, my dad, who’s who’s now retired, was a professor of French and and francophone literature at Skidmore College. I so distinctly remember being a kindergartner in Saratoga Springs, where the college is located, and showing up on the first day of school, not speaking a word of English. French and Arabic are my first languages, and feeling this kind of eternal sense of being a misfit, and that has been a through line in my life. And growing up in a town where there weren’t a lot of immigrant families like ours. Um, I was lucky to have access to this beautiful campus, thanks to my dad. That lessened the isolation of of being a misfit at that age. When you’re young, the last thing you want to do is stick out. Uh, assimilation for me, was social survival. I, you know, used to beg my parents to let me legally change my name to Ashley. Um, that sort of stuff. But by the time I was a teenager, about 1213, I started to embrace the fact that I couldn’t fit in and to make use of this extraordinary college campus that, you know, offered a host of not just classes that I could take for free, but also summer camps. And so the summer I turned 13, I was in an orchestra camp affiliated with Skidmore. And at the same time, there was a jazz camp that was taking place. And that was where I met a young, very awkward young man named John Batiste, who, you know, is now my husband. Uh, but Skidmore, for me was, you know, not just the place where I ended up meeting my future spouse, but it was the place that I attended when I was 16 years old and dropped out of high school because I was pursuing at the time, the double bass and the deal with my parents was that I could focus on going to conservatory, but that I had to at least take two days of classes at Skidmore.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:04:14] And this may sound like an irresponsible parenting decision to let your daughter drop out of school, to become a double bass player and a classical music orchestra, which is not really the most viable career path anymore, especially in a country that, you know, has a waning appreciation of classical music. But, you know, I grew up in a house that really valued the creative arts above anything else, and the sort of unexpected thing that happened in the course of, of taking these classes at Skidmore to appease my parents is that I absolutely fell in love with my academic experience there and decided that I wanted to go to college after all. And that sense of freedom at 16 to study anything I wanted, which for me, you know, meant signing up for a modern dance seminar and a class on Nabokov and memoir and all kinds of things, just to have the freedom to pursue whatever piqued my curiosity without worrying about it amounting to anything, actually, you know, set me on a path to identifying what it was that I wanted to do, which was, you know, not just a deep love of music and dance, but a deep love of the creative practice and storytelling. And so it was pretty surreal to return this fall. My first book, Between Two Kingdoms, was assigned as the first year Experience book, which, you know, was a brave choice in a way. It’s not your conventional.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:00] Yeah.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:06:00] Incoming freshman book. And to get to speak to these students. And, you know, I was so moved by the questions that the students posed. And I think, you know, the generation of students that are graduating from high school and entering the real world in some ways have had it so much harder than many other generations. They’ve lived through a pandemic, they’ve lived through enormous political upheaval. And much like the rest of us, there’s this sense of deep uncertainty in the air. And to get to speak both about my own kind of unconventional path at that age, and to speak to You how and you know the context of my own life. I’ve had to figure out how to navigate that sense of heightened certainty. Um, it was a gift. And, you know, also pretty fun to have my dad there and all of his colleagues.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:06] And how cool is that?

Suleika Jaouad: [00:07:07] Uh, it was so cool. I’ve never been more nervous in my life. The only thing more intimidating than a group of 18 year olds who desperately want to convince you that you’re cool, uh, is a group of 18 year olds. And your professor father.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:24] Uh, as you’re, like, literally saying that I remember the first time that I knew my mom would be in the audience when I was giving a keynote. I was petrified, absolutely petrified. Like I’d spoken for thousands of people in theaters before. And I’m like, okay, I know my mom’s going to be in the front row. Why am I going to do? I was just completely freaked out, but it was it was actually really beautiful experience at the end of the day. And like, she got to see me doing my thing and it was. And like, I couldn’t have described it. But when she was in the room and part of the energy, like she was like, oh, I get this. And it was just it’s a, it’s a it’s a really neat way to share. Terrifying as it may be. I mean, from what I understand, you’ve written about this like there was an interesting moment during that talk to, you know, it came to the Q&A part of it. And basically somebody said, hey, like, you know, for somebody who’s my age now, like, what would you do? And, and you had a really interesting response, which was basically like, don’t single channel yourself if you’re somebody who has that one passion and it’s consuming, awesome. But if you’re like, if there are five parts of you that you love and treasure and savor, then like, let those be centered in your life, which is different from a lot of the messaging that I think people get these days.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:08:36] Yeah. You know, there’s such an emphasis on finding your passion and translating that into your purpose and figuring out how to turn it into a profession. And, you know, I just really believe that that kind of messaging does not only a disservice to, you know, young people who are very much figuring out who they are. But to all of us, no matter how old we are. You know, when I think back to my early childhood, I had so many interests and even already at that age felt a kind of sense of shame around it. I remember someone saying to me, like, you’re always going through a new phase. And I took that to be a kind of criticism, like I really needed to stop flitting about and to really hone in on something and, and pick my path and ideally, you know, take what are those called advanced college courses, uh.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:40] The.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:09:40] Aps.

Jonathan Fields: [00:09:41] Yeah.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:09:42] Um, and be really strategic about what college I went to to make sure that it synced up with whatever it was I wanted to do. And I had no idea who I was. And, you know, in the process of writing this new book, I’ve gotten to revisit a lot of my old journal entries from the time that I was a kid, and I found this entry from when I was about 12 years old. That same summer, I was on my way to band camp. That same summer, I met John and I wrote a list of my goals and predictions, and they’re kind of hilarious to me because they’re the opposite of careerist. Like, my goal was to paint graffiti on toilet seats, uh, to, um, take my double bass case and turn it into a costume by cutting eye and mouth holes in it, and to wear it for Halloween. It was, like, totally absurd. But I loved that because when I fast forward about just a couple of years later and look back at those journals, the journals I had in college. They’re all aspirational and a kind of heartbreaking way. And it’s, you know, one year and five year and ten year lists about who I feel like I should become and what I feel like I should be doing.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:10:59] And so much angst about the future and about becoming a person of importance and value and a way that might look good on a resume. It’s I’ve, you know, I lost that sense of freedom and curiosity and playfulness that, that so many of us naturally have as children. And so when I think back to my college self and I read back those journals, they’re incredibly boring. I have no idea what I was feeling or actually thinking in the moment. It’s all about some aspirational self and a really kind of conventional way. And you know, what I said to those students is very much what I wish I could have allowed myself to do, which was, you know, the freedom to take courses in fields I knew nothing about before feeling this pressure to identify a major and beyond college. I’ve in recent years, really made it a practice to try to allow for that kind of expansiveness. You know, our mutual friend Elizabeth Gilbert says you have to be 1% more curious than afraid. And that when you follow your curiosity, that’s such a gentler way in than feeling this enormous pressure to identify a purpose or a passion.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:25] Yeah. I still love that. I mean, both the notion of following your curiosity and also just 1% more than you are afraid, because so many we feel so often like we’ve got to be sure, we’ve got to be really confident about this thing, you know, like we’re doing this. Internal cost benefit analysis and expected return analysis. And what’s my likelihood of succeeding in this thing? And it’s like and we set the bar really high. Well like I’m not even going to bother trying unless I think I’m going to have a 75 to 80% chance of like, being good at this or enjoying it or succeeding at it. And meanwhile it’s like a nobody knows in advance. Yeah. You know, and be like, if you set the bar that high, you’ll never take an action about anything that you’re curious about in your life, because you’ll just keep talking yourself out of it and you just kind of stay in this own this, this little cage of your own creation, wondering why life isn’t happening for you. And that’s the way that so many people live.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:13:24] Absolutely. And it’s, you know, it’s that distinction that the journalist, uh, David Brooks makes between our resume virtues, the virtues that make us attractive and a modern job marketplace Context and the cultivation of our eulogy virtues the qualities and characteristics that were lauded for often, once we’re no longer here, you know where we kind were we brave to be? Take creative risks, even if the cost benefit analysis didn’t make sense. And I think, you know, we live in a culture that that more than ever is obsessed with productivity and output. But when we’re all, you know, on that hamster wheel, it feels like surviving and not actually living.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:18] Yeah. I mean, what if, you know, I’m not somebody who tends to look at ways to measure life, but I think productivity is sort of like the common one, like you just described. What have you made? What have you created? You know, but like if we were going to use a metric, what if it was, you know, like how much have you closed the gap between who you genuinely are and how you move through the world? You know, like, what if we just. What if if we had an aspiration? What if it was just that?

Suleika Jaouad: [00:14:46] Absolutely. Um, you know, when I got sick at 22 and all those resume virtues were foreclosed upon and I was not a person of value or import in the modern marketplace, right? I wasn’t working, I wasn’t posting anything on social media or doing anything that felt social media worthy. I was back in my childhood bedroom. I was in the hospital. I was my most stripped down, laid bare self. The question was no longer who am I going to become? But what nourishes me? What makes me feel most alive today? And I had, you know, really limited energy. I could maybe do 2 or 3 things a day. And so that kind of constraint, even though it was incredibly frustrating, proved useful. And in asking myself what actually matters to me, I only have about two good hours. Who do I want to spend it with? What do I want to do during those two hours? And it was never the things that would exist on a resume.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:00] Yeah, I mean, for for those who don’t have the expanded context, when you were 22, you were diagnosed with leukemia, ended up going into treatment for what you thought would be like 22 a couple of weeks and in and out of the hospital, in and out of all sorts of really brutal treatment for the better part of four years. Um, and so, so, like, your life was just profoundly, profoundly changed. This eventually led to you taking the practice that had been a part of you for so long, journaling, and actually blending it with I, if I’m remembering this correctly. Um, sort of like the idea from Michael Beirut, who’s this legend in the design world and the creative world? You know, like just stunning, stunning mind of creating 100 day projects. So you’re like, let me, let me actually, in a really, really rough time where I’m really having trouble even showing up to have the energy to write. Let me actually see if I can commit to writing for 100 days. That eventually becomes more of a public project with life interrupted, which ends up being a column, a video series in New York Times, and in a really interesting way. You just saying, let me, let me take the few hours I have every day to feel the way I want to feel and be with the people I want to be. And then just as much as I can write about it like that becomes something that then starts to set a trajectory for your life in a really interesting way.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:17:23] Yeah, yeah. And no part of me felt like doing 100 day project. No part.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:28] Of me. Yeah.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:17:29] Was like in a creative mood or feeling particularly inspired. I was 22 at that point, you know, I would spent, uh, I think, about six weeks in the hospital. Um, I was angry, I was miserable, I was scared, and, you know, none of the chemo I was doing was working. My leukemia was becoming more and more aggressive. And I felt, you know, this deep sense of despair. And, you know, the interesting thing about despair is when you get, you know, to a real low down place where you’ve been really brought to your knees. For me, it felt like there was a pretty clear choice. It was like I needed, even if I didn’t want to, even if I didn’t feel particularly motivated, like I knew I could just stay in that despair, or I had to kind of figure out how to vault myself out of it. And I wasn’t quite sure how to do that or what that would look like. But I knew that something needed to shift. And this idea of alchemy, which is the setting of the Book of Alchemy, but is not something that was really in my mind, but I’ll never forget. And this is related to the 100 day project.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:18:46] The day that I got that news that chemo had not worked, the leukemia was getting worse because it happened to be the day that John, my old friend from Bandcamp, learned I was sick. And then I was in the hospital and he left rehearsal with his band, and they went straight to the hospital and announced uninvited. And they put on this impromptu concert for me right there in my hospital room. And as the sound of John’s melodica and, you know, Joe’s tambourine and a band tuba started to float out into the hallway, different patients and doctors and nurses started to file out of the rooms, and we all ended up in the hallway and we started Clapping and and singing and dancing. And it was such an extraordinary moment because a hospital is a depressing place. The only thing more depressing than a hospital is maybe a cancer ward where, you know, the only sounds you hear are the mechanical beeping of monitors and the wheezing of respirators and and to feel. That energy transform and to feel, you know, that shift from from sorrow to joy, that shift from isolation to a kind of connection. That was a really powerful moment for me and kind of set me on this path of thinking about how I might begin to alchemise creatively alchemize my, my own, you know, relationship to these circumstances.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:20:26] And so the 100 day project was the beginning of that. And, you know, I think felt really daunting to me because I wasn’t confident that I could actually see it through, and I didn’t need any more reasons to feel bad about myself if I couldn’t. And so journaling to me felt like, you know, a thing you do for yourself. It’s private. There’s no audience. It’s not supposed to be good writing. It doesn’t even need to be grammatical writing. It can be fragments. It can be doodles. It can be lists. And I went into it with a couple of rules to make it manageable. The first was that I should aim for three pages, but any amount would do. And so sometimes it was three pages. Sometimes it was a sentence, sometimes it was the F-word. Um, and that was it. And that I couldn’t reread it because I didn’t want that kind of critical mind of. And that kind of performative impulse that creeps in when we feel like we have to be good at something, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:21:25] It’s like writing to judgment.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:21:26] Yeah, totally. And so it was such a liberating experience to keep that journal. And, you know, I’ve been a lifelong journaler, but I think, like a lot of people struggle to do it consistently and have more journals that I can count where I maybe fill out the first couple of pages and leave the rest blank. Um, and so that container of 100 days, thanks to Michael and, and that sense of community and accountability that came from doing it with my friends and family proved really useful and was something that I ended up returning to again and again over the coming years.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:05] Yeah, I mean that it’s interesting, right? The notion of both of journaling, the notion of 100 day project and the notion of alchemy, it seems like they keep they keep finding this way to dance with, with each other in new and different and creative ways, and also just the notion of alchemy into creative expression. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors.. You end up transmuting this 100 day project also, then into a 15 000 mile solo road trip, which then becomes deeper awakening, deeper writing, deeper insights. Eventually, it becomes the source of Between Two Kingdoms. Your last book really just sort of like describing this experience and this. And then we landed in the pandemic, you know, where, yes, everybody is is going through a moment. The world is going through a moment. You end up in your own moment with a recurrence. And at the same time it’s interesting. And you write about this, you know, you’ve had this training at that point.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:23:13] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:14] And how to step into experiences like this differently than almost anybody else. And it feels like that allows you I’m not going to say, to just do this whole thing with more grace, because I think that’s not what happened. But but it allows you to experience the last couple of years, like the pandemic years, very differently.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:23:36] Yeah. Yeah. So, you know, I when I last came on the podcast Between Two Kingdoms had just come out and I was talking about survivorship and the challenges of that. And, you know, the irony was that I was sick then and I didn’t know it. And I, you know, I been in remission for about a decade. Uh, there was a less than 1% chance at that point of the leukemia returning. And and yet it did. And so when, when the ceiling caved in, of course, it was terrifying and traumatizing. And I had, you know, thanks to keeping a journal, thanks to writing about that experience Between Two Kingdoms. I thought a lot about what that experience had meant for me, and how I wanted to apply that knowledge going forward, and even how I might navigate things differently if I got sick again. And so, you know, as much as a the misfortune as it was to have this recurrence, I also felt fortunate to be able to go into it with that knowledge. And I want to be careful here because, you know, I don’t believe that going through something traumatic makes you wiser or braver by default. There’s that old Hemingway saw that, you know, the world breaks you and you are stronger in the broken places.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:25:13] And I don’t believe that. That’s where, you know, the element of agency comes in. You know how we choose to respond to the circumstance. And that choice to me is is where things get interesting. Because as much as you know, it’s easy to feel powerless when you get sick or, you know, when your life is upended in some kind of way, there’s always agency available to us. Or at least that’s the thing that I try to anchor myself back in when things feel like they’re they’re spinning beyond my control. And so, you know, when I got sick again within 24 hours, you know, my life completely changed. My husband, John and I were making all kinds of plans. We, like a lot of couples, were waiting until the pandemic was over, as over as it could be to have a big wedding. We were talking about kids. We were, you know, future dreaming and planning. And pretty much overnight we found ourselves packing up our house, finding friends to care for our dogs and and back in the hospital where I was preparing to re-enter treatment and to hopefully undergo a second bone marrow transplant. Um.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:41] I mean, and there’s really interesting sort of contrast at the same time. This is actually beautifully documented, and you end up having a documentary created about this, this moment in both you and John’s life, where you’re going through this just like extraordinarily challenging moment and at the same time, simultaneously from the outside looking in. John’s having the best year of his life.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:27:07] Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:08] Yeah. You know, he’s like, exploding as a public figure, as a musician, as like, he’s working on this incredible symphony that would be formed, you know, in this legendary hall in New York. And meanwhile, like, you know, like you’re you’re both so deeply connected that you’re both navigating both worlds simultaneously, you know? And it’s just this really powerful exposition on the duality of life and how sometimes we don’t get to choose, like all the good and all the hard, um, it just happens all at once and it’s like, how do you how do you be with all of it? How do you acknowledge the fact that this is real? This is my reality to the extent that I can change it, I will, but to the extent that I can’t. Like, how do I do this? And it’s such an interesting moment for for both of you.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:27:56] Yeah. That that forever work of figuring out how to hold both the cruel facts of life and and the beautiful ones in the same palm. And you know, I’ll never forget that day. It was my first day of chemo. John and I are on our way to the hospital and suddenly his phone starts ringing, and he had opened his phone and discovered he’d been nominated Did for I think it was 11 Grammys, a record number, I think, tied only with Michael Jackson, something absurd like that. And we were just in these kind of parallel moments that felt oceans apart. And, you know, as exciting as that was, John’s immediate impulse was, I’m not doing any of that. I want to be here. And for me, especially having known him from the time that we were teenagers, having watched him work so hard, not towards a moment like this, because I don’t know that you can ever anticipate a moment like this, but watch him work so hard. It was important to me that he got to live it. And also, of course, important for us to figure out how to stay connected. And so, you know, one of the very first things John said to me about 48 hours before I was admitted to the hospital was, let’s get married. Let’s get married tomorrow.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:29:25] You know, we had a plan, and we were not going to let this situation get in the way of that plan. And what greater response to life’s sorrows than a proclamation of love. And so we got married in the living room of the house that we just moved to in Brooklyn. It was completely empty. There wasn’t a stitch of furniture. And we, you know, had bread twists as rings and just this tiny handful of our very closest friends who had been able to quarantine to kind of help protect my immune system. And we ordered fried chicken sandwiches and, and had champagne. And it was, you know, not at all what we’d imagined and infinitely better. And so I went into that transplant unit brimming with love And also brimming with ideas based on my prior experience of illness, about how I was going to navigate that period of, you know, isolation in the hospital. And because it was Covid, it was, you know, a step further than the typical medical isolation that you’re in when you have zero white blood cells and and no immune system to do battle for you. I was only allowed one visitor a day between very constrained hours. And I was, you know, preparing to be in the hospital for about a month. And pretty immediately things went south.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:30:55] Um, I, you know, had packed with me about six different journals. I had my private journal. I had my kind of reporter’s journal that I had written, um, on the cover of it. Observations from the nurses station. I had my journal with John. Um, John and I have had a long standing practice of writing each other letters in our journals and snapping photos of them and texting them to each other. Um, and my medical journal so I could write little notes down during the doctor’s round. And fast forward a few days later, and I was on a cocktail of medications that impaired my vision. For about two weeks, I could barely see. Uh, I was seeing double. I was seeing triple. Um, and so that meant that that writing the thing that had always gotten me through was not really available to me, at least not comfortably. And the other thing that happened is that John got exposed to Covid at work. And for about a 20 day period, was not allowed to visit me in person. And the last thing that happened is that our dear friend Elizabeth Gilbert, who was watching my dog, um, called me, uh, one day about a week or maybe ten days into that hospital stay. Um, when I was, you know, doing battle with with multiple blood infections and really not in a good place, uh, to let me know that my dog had been diagnosed with cancer and needed to be put down in the next two hours.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:32:42] And so, you know, that confluence of things is the kind of thing that, you know, can break a person. And I certainly felt that I was at my breaking point. You know, my new husband, my creative coping practice, my faithful best friend who’d been with me, you know, since I was 22 years old, all of that was was gone. On. And, you know, I had again that moment of of feeling that deep sense of despair and feeling a kind of choice present itself. And so, you know, that night I had this very clear vision. It was the middle of the night I woke up, I was so distraught of a wooden marionette being lifted by four birds. Um, and I took out a piece of paper, and a friend had gifted me some watercolors. I’m not a trained painter. And I started to paint that vision, that kind of weird hallucination. And as I painted the marionette and the birds, and as I started to paint the strings connecting the birds to the marionette, I felt my spine lift. Um, and again, that that sense of alchemy.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:34:05] I ended up keeping a visual journal, uh, and doing a little watercolor of these bizarre medication induced hallucinations I was having that were honestly kind of scary. Um, but in the process of transcribing them became interesting to me and John and his own act of creative alchemy, though he couldn’t be physically present, started composing little lullabies, um, and sending them to me. And I would play them on loop on my computer. And it was his way of enveloping me with his, his presence and love at a time when we were apart. And sweet Liz, I’ll never forget on Valentine’s Day. Very, uh, sort of in in the dark of the night on York Avenue, right below my hospital room window. I was up on the eighth floor, made a little heart out of LED lights, and spelled out my name. And so when I looked out there that night, I saw that that beautiful message. And though she couldn’t visit me, it was again, you know, that that sense of connection that I think is available to us always through through creativity. And so, you know, not not the thing I had planned, but maybe the lesson that I needed, which is that, you know, survival is its own kind of creative act, whether you consider yourself particularly creative or not.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:37] Yeah. I mean, just so powerful in so many different ways. The, um, I love also how you were able to to take this practice that had been your coping mechanism, your creative expression for literally your entire life. And in this moment, you know, went into the hospital literally saying, okay, so like, this isn’t what I wanted, but I’ve done this before, like, and like I kind of I have a maybe a little more of a plan. And you had your six different journals and like that all got blown up And and your brain says, and maybe this wasn’t a conscious, willful, logical thing. This was like a fever dream type of decision where you’re just like, this thing just came to me like what is accessible to me in this moment? You know, like if I am a creative being and my whole life has been a creative act and I want to sustain that as much as I can, because maybe it’s going to help me through this, what is available to me and for you, like the written word wasn’t available in that moment in time, but visual language, visual expression was. And that became rather than you saying, But I’m I’m a writer. I’m a journaler like, I can’t do the thing I’m here to do. You just kind of said, like, this is what I have available to me. Let me run with this. Let me let this become my thing for however long. And what’s stunning is that I don’t know if you were a visual artist before, I can’t remember, but now visual art is is a is a really meaningful big part of your life in a way that, from what I know, it really wasn’t before. Like, this has become something beautiful that’s a part of your everyday life now.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:37:15] You know? And I want to go on record and say that, first of all, I’ve, I’ve tried lots of creative things that do not become a big part of my life. Um, so, uh, I feel like that’s important to say.

Jonathan Fields: [00:37:29] Yeah. Duly noted.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:37:31] Yeah, yeah, yeah. Um, and, you know, and it wasn’t it wasn’t part of some grand plan. Um, it was this moment of I have so much angst, so much despair in my body, and I need to get it out. Otherwise it’s going to kill me. And so, you know, those those nightmares, right, that were so terrifying to me. And the process of transcribing them, you know, you become the handler of the thing you fear rather than the hand-build. And so that felt good. And so the next day I did it again. And the day after. And, you know, by the end of my hospital stay, the walls of of my hospital room were covered in paintings, and the nurses would come into my room and, you know, look forward to seeing the next apparition taped to the wall. And this young woman who would come to clean the floors told me that she would always clean and for longer than necessary and linger, um, because it made her feel good to be in this room. That was a weird, surreal kind of art gallery. And again, you know, much like that first 100 day project, the goal was not to create a body of work or to turn it into some, you know, into fodder for some art exhibition. It wasn’t the goal wasn’t even to be a good painter or a bad painter. It didn’t really matter at all. The point was creative expression. It was that transmutation of whatever was swirling around inside of me into something of my own making.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:39:17] And that for me, you know, has been my way of being in conversation with the self and therefore, you know, feeling like I get to be in conversation with the world, even if, you know, the reality was that I couldn’t step outside of that room. It was, you know, when we talk about alchemy, we think of the transmutation of something worthless and base and, like, lead into something precious and noble, like gold. Um, and so it felt like my own private act of alchemy. But I think the important piece here, you know, to to go back to the Skidmore students was that I wasn’t doing it with a goal. Um, if I had done it with a goal, the ego would have immediately chimed in. The voices of insecurity and doubt would have said, you know, you’ve never studied this. What’s the point? You’re going to embarrass yourself. These are stupid, whatever it might be. And I was getting to, you know, in the the weird container of the hospital that sort of set apart from any expectation of productivity getting to, you know, tap into that 1%. More curious than afraid to follow that thread of intuition without caring where it might lead. And to me, at every juncture when I’ve allowed myself to do that, the irony is, of course, that it’s it’s yielded something incredibly valuable, whether anybody knows about it or not.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:00] Yeah, it’s like the like rather than going into it saying, like, I’m doing this so that at the end of it I can have X, you do it simply for the experience of doing it. And it seems like just as you described, every time you’ve done something like that, there’s, there’s like a purity in it, you know, and, and something kind of gorgeous emerges on the other side, you know, whether it was life interrupted, whether it was the book, whether it was the new book, you know, the book of alchemy, which, you know, through this experience and also the experience of bringing together community to journal collectively through the experience of the pandemic, um, which leads to the isolation journals where you create this just stunning global community and then reaching back into your past, into this realization, you know, in your earlier days that, oh, like when you can actually just have the seeds of a prompt in the form of somebody else’s writing or ideas or experiences, it’s really helpful to you. And then so you start to invite people into it. And then this leads to a book, you know, the book of alchemy, which is now like this offering to everybody else, you know, to say, what if we took 100 days? Here’s, here’s effectively, I don’t want to say a roadmap because everybody needs to travel their own thing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:22] But here, here, here are 100 prompts divided into ten different sort of categories that might be interesting for you to explore, each one provided by a different writer, so that if it’s interesting to you, maybe you can experience the same kind of alchemical transformation through the process of just showing up every day, whether it’s one word, whether it’s five pages, whatever it may be, and I’m going to help you, and I’m going to bring in 100 stunning minds and writers and hearts and souls to help. Just plant seeds for you to get you going a little bit. Um. I’m curious, I want to I want to dip into just a couple of different parts of that book for you. When does your own. Okay, so I’m moving through another season. I’m doing this thing. I’m doing it differently in my own life. But, like, when does this make the transformation from this is what I’m doing for me to, oh, this could be something beautiful that can become an offering to others now.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:43:29] So for me, it always starts with the resistance. Um, I very much tried not to write this book for a lot of reasons. I think, you know, journaling has a lot of associations, but it just seems like the self-evident thing, like uncap a pen and write some stuff down. What could be so hard and, you know, despite the mountains of evidence that that show us the benefits of journaling. Like I said earlier, you know how many of us have have bought a journal with the best of intentions of using it, and only filled out the first couple of pages and left it blank. And in the beginning of the pandemic, when we all went into lockdown, so much of that experience felt familiar to me. You know, the face masks, the, you know, isolation rules. Um, the challenge of figuring out how to feel a sense of connection when you’re stuck at home, um, when your life as you know, it has imploded. Except that, of course, this time we were all living that and navigating that in real time. And so I decided to start a newsletter called The Isolation Journals. It was meant to be a 30 day project, um, which became a 100 day project. Uh, but this short lived thing where because I know how challenging it can be to journal when you’re not feeling particularly inspired or reflective. Um, even though that’s usually when it’s most beneficial to invite some of the most creative minds I knew to share an essay and a prompt.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:45:14] And you know, I’m someone who, in my younger years, if I’d been instructed to write to a prompt, would have said, absolutely not. Um, always seemed like homework. But also as someone who’s, you know, been keeping a journal for many years, I know that sometimes, you know, it’s it’s when you’re stuck in a thought loop or stuck in your life, it’s easy to get stuck in, in, in your own reflection. And I need something to kind of ignite some spark that twists my mind out of its usual rut. And for me, I’ve always found that in reading and in some kind of inquiry, which is to say, a prompt. And from the very beginning I was very clear that, first of all, you don’t have to write to a prompt. You can use it as a thought prompt. You can use it as a conversation prompt. You can write about how much you hate the prompt. They’re really meant to exist there as a sort of mirror, showing you either what you find, uh, resonance and, and or what repels you. Either way, it’s kind of interesting and that there’s no special skill that you need. Which to me is why it’s always been the most accessible way into cultivating a creative practice. You know, you don’t need to be a writer.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:46:35] You don’t need fancy equipment. You don’t need to have taken a course. It doesn’t even need to look like writing. It can be songwriting. It can be your form of journaling can be, you know, in in playing the piano, which is what my husband does, or voice memos when he’s wandering around the house. It’s really capacious in that way. It contains anything, and there are no rules. There’s no wrong way to do it. And to my great surprise, within 48 hours of starting the isolation journals, because people were stuck at home because they were looking for a way to stay grounded and stay connected to each other, we had over 40,000 people who had signed up, and some of my very favorite individuals and stories that emerged from that project are what made me want to write this book. There was a woman named Joelle from Minnesota who lost her 13 year old daughter, and she decided to use her daughter’s art supplies to create a visual journal entry. Each day, a little memory of her daughter and the way she described it, was that she felt like she was in collaboration with her daughter that she was keeping a kind of grief journal that allowed not just for for the immense, unspeakable pain of that loss, but also for the joy of of remembering her, of getting to visit with her. And so she continued that visual journal long after the Hundred Days.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:48:09] Um, another story that comes to mind is Charlie from Minnesota, an 80 year old grandfather who never journaled before and who was feeling isolated before the pandemic and certainly isolated during it. And he started doing a daily journal and sharing his entries with this sort of global virtual community. And he’s still one of our most ardent community members. And the way he describes journaling is it feels like an adventure, and I have no idea where it’s taking me. But the best part is that I no longer need to know. And so I had started to think a lot about journaling and all it can contain, and started to think about these, you know, extraordinarily creative minds who’ve helped me shift the cylinder, um, and allow light to fall in a different way. And, you know, in the last year, year and a half, as I was recovering from that bone marrow transplant and trying to find creative ways to alchemize my own sense of isolation and to a kind of creative solitude and connection. The answers and the questions that kept emerging were the ones in the journal. Um, and so in writing this book, you know, I revisited I think I have over 100, 200 journals since childhood, um, and started to notice that the same old themes came up. And so this book is divided into those ten themes that most frequently came up, which I think are the themes that probably most frequently come up for many of us.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:49:55] You know, there’s a chapter on love. There’s a chapter on fear. There’s a chapter on purpose. And that began to inform the framework of it. And so, you know, really it’s it’s kind of like a memoir in essays, not just my own, but the 100 contributors. And my very favorite part of getting to write that book was getting to curate that extraordinary collection of voices, those incredibly brilliant, creative minds. And when I say brilliant creative minds, I don’t mean, you know, the famous authors and musicians. There are some of those in there, you know, the George Saunders and the Elizabeth Gilbert’s of the world. I think, you know, for me, I interpret that very broadly. You know, there’s um, at the time he was 7 or 8 years old. A contributor in the book, two time brain cancer survivor who shared a beautiful essay and prompt. There’s a young man who is re-entering the real world after a long prison sentence. There’s a young mother who, you know, writes a beautiful essay as she’s on the the verge of widowhood. And so it’s really a collection of, of the people who have embodied that idea of, of creative alchemy and who’ve inspired me to find ways to tap into it in the context of my own life.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:27] And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. I love the way that you’ve approached this. I also love just the voices that you’ve assembled for this. Um, and it’s interesting. I’ve been I’ve been using it in a sort of a different way of journaling. So like, I’m very fortunate. I live in Boulder, Colorado. I hike, you know, on a very regular basis. I’m out in the mountains, in the woods for an hour and a half, two hours, many days of the week. And I’ve actually started my own form of what I would just almost call, like walking, journaling. Like I would read a prompt from your book and it would, I mean, a like there’s so many beautiful writers who are sharing these aren’t these aren’t just prompts. These are just beautiful pieces of writing, of thinking, of feeling that get into you, that get under your skin and into your heart and into your mind. And I would read them and then, um, you know, and it takes me 2 or 3 minutes to just read through this. And then I would go out for a hike, um, and I would hike with it. And like, my form of journaling with your book has kind of become I’ll read something, you know, almost flip open to a random page in one of the ten categories. I’ll read the prompt and then I’ll just go walk with it in the woods for an hour and a half and see what emerges. And it’s it’s, um, it’s been just this kind of magical experience. It’s super cool.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:52:56] Oh, I love that so much. I mean, you know, that’s nothing could make me happier than these prompts being used in creative ways than the notion of journaling and its conventional sense being exploded. I sent the book to a friend of mine who has two young kids and is in a book club with some of her her dearest, dearest friends, all of whom are also very overwhelmed, exhausted young mothers. And she, in their last book club meeting, um, read one of the prompts and asked everyone if instead they could journal together for ten minutes and like some of the moms were like, okay, that’s not really my jam. And others were like, I’m never going to have time to do this, but whatever, we can do it for right now. And afterwards, you know, they talked about what came up in their journal entries, and some even shared their journal entries. And she called me yesterday and she was like, I’ve known these women for a long time. And I learned things about my friends that I have never learned before. And we don’t have time right now or, you know, to do it every single day. But we’re going to keep working through the 100 essays and prompts together, no matter how long it takes us. And I love that so much because again, you know, it’s it’s that that sense of connection to the self that I think allows us to feel connected to the world and our fellow humans in it. And yeah, I’m so I’m so happy that they’ve offered good fodder for your walks and the woods.

Jonathan Fields: [00:54:40] Yeah. No, it’s been really beautiful. And in fact, shortly after this conversation, I’ll be doing the same. So I look forward to flipping open to, like, whatever page I land on today and, uh, and, and meeting the ideas in the woods. Um, it feels like a good place for us to come full circle in our conversation as well. So I’ve asked you this question before. It was a number of years back, um, and you were in a different place and the world was in a different place. But in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Suleika Jaouad: [00:55:10] So, you know, I found out in August that my leukemia is back for a third time. And it’s been really interesting, you know, navigating this new chapter of illness and and all the uncertainty and, and what ifs that come with it. And when I expressed that to my doctor, my wonderful doctor, and I said, I just don’t know, you know, how to do this. It feels scary and it makes it hard to plan a couple of months ahead without, you know, fearing the future and and wondering if I’ll get to exist in that future. His advice to me was the kind of advice that lots of people reach for when someone’s in this situation. And, you know, he said to me and has said to me more times than I can count, you have to live every day as if it’s your last. And as well-intentioned as that advice was, every time he said it to me, I would feel this intense sense of panic like, I have to, you know, carpe diem, the shit out of every moment and every day. And everything has to be meaningful. And every, you know, gathering with my loved ones has to be beautiful and make it into the memory bank. And that is an exhausting way to live. And it’s certainly not sustainable. And just a lot of pressure.

Suleika Jaouad: [00:56:37] And so I’ve come to believe that while it may come from a good place, it’s really bad advice and that we if we were all, you know, to live every day as if it were our last, our world would be chaos. We’d be emptying our bank accounts and declaring bankruptcy and doing all kinds of things. And so for me, you know what living a good life has come to look like is a much gentler kind of twist on that advice, which is trying to live every day as if it’s my first. And to go back to that sense of childlike curiosity and wonder that we have access to, you know, with such ease when we’re little and that we lose as we get older and to wake up like a little kid might and to do what delights me. And that’s rarely the big bucket list items. It can be pausing to admire, you know, a caterpillar scuttling across the grass. It’s, you know, hanging out with my three dogs. It’s embarking on a new creative project just for the hell of it, without sense of expectation. And when I do that, when I take the pressure off, when I allow myself to tap into curiosity without any expectation or outcome, that’s when I feel most alive. And so to me, it’s it’s that right now.

Jonathan Fields: [00:58:26] Mhm. Thank you. If you love this episode you’ll also love the conversation we had with Elizabeth Gilbert about unlocking creativity and reinventing your life. You’ll find a link to that episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help by, Alejandro Ramirez, and Troy Young. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle Bliss for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project in your favorite listening app or on YouTube too. If you found this conversation interesting or valuable and inspiring, chances are you did because you’re still listening here. Do me a personal favor. A seven-second favor. Share it with just one person. And if you want to share it with more, that’s awesome too. But just one person even then, invite them to talk with you about what you’ve both discovered to reconnect and explore ideas that really matter. Because that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.