What if a poem could change your life? Have you ever read something that felt like it cracked your world open, giving words to experiences you thought were unutterable? My guest today, Maggie Smith, experienced exactly that – but not as the reader. As the writer of the poem, “Good Bones.” After being rejected by many journals, the poem was published online and quickly became a global phenomenon. Her life would never be the same. But, in so many ways she never saw coming.

What if a poem could change your life? Have you ever read something that felt like it cracked your world open, giving words to experiences you thought were unutterable? My guest today, Maggie Smith, experienced exactly that – but not as the reader. As the writer of the poem, “Good Bones.” After being rejected by many journals, the poem was published online and quickly became a global phenomenon. Her life would never be the same. But, in so many ways she never saw coming.

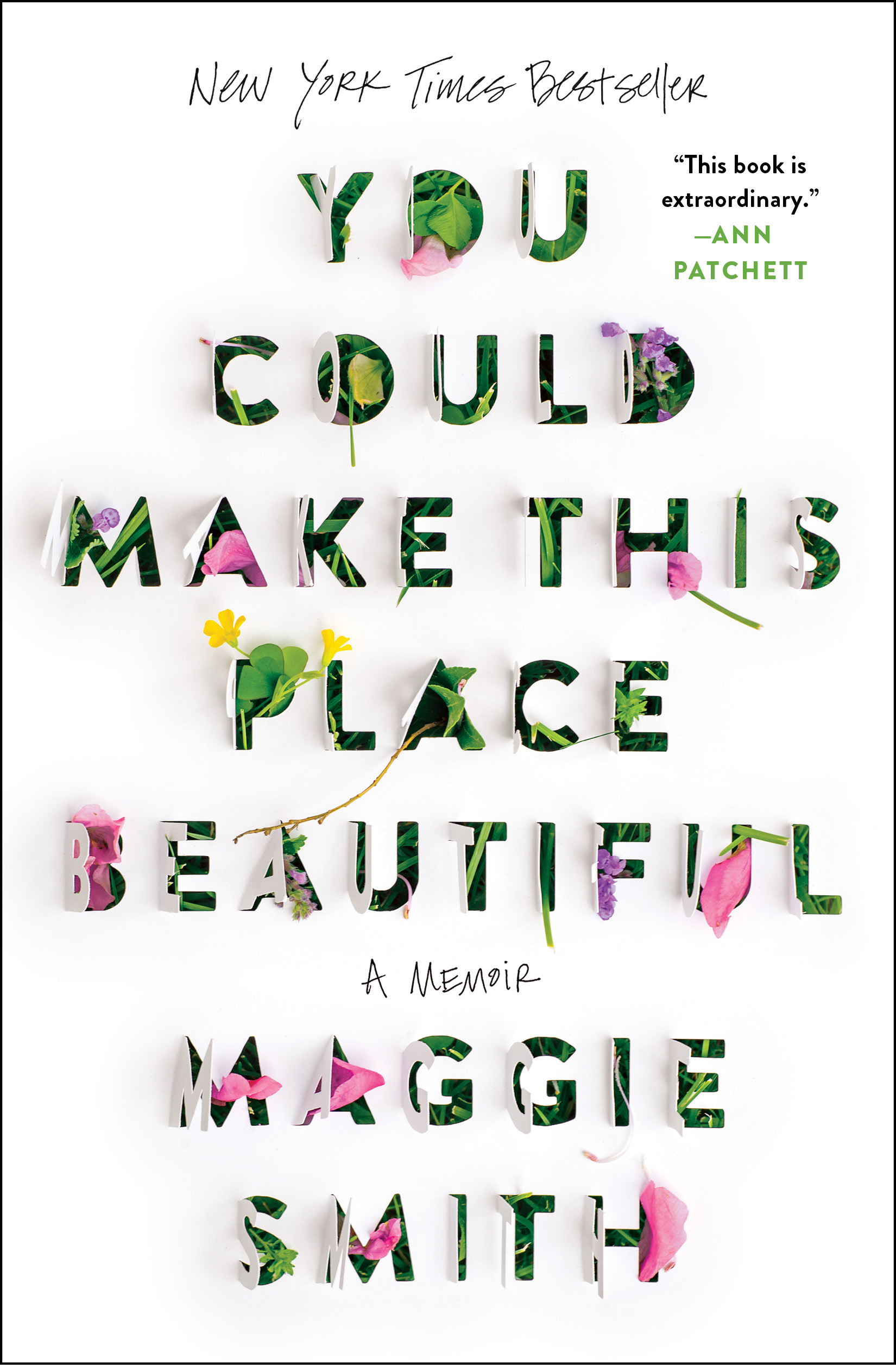

Maggie is the renowned author of multiple bestsellers and award-winning poetry collections, with her work appearing in top publications. In her memoir, You Could Make This Place Beautiful, Maggie unflinchingly explores the disintegration of her marriage, contemporary womanhood, and her renewed commitment to herself, weaving together snapshots of life with meditations on secrets, anger, and narrative itself.

In this deeply honest conversation, Maggie shares how music became her first poetic teacher, allowing her to transcend the constraints of plot to distill pure experiences into lyrical language. We explore the fateful chain of events that led “Good Bones” to captivate millions during a collective moment of trauma and suffering.

And, Maggie doesn’t shy away from the contradictions – how mega-success also revealed chasms in her marriage and life, how she leaned on art to help metabolize hardship, and the liberation in embracing life’s “unanswerable mysteries.” She offers insights that will resonate deeply with any creative soul who has grappled with the complexities of success, relationships, and honoring their truest self. With disarming authenticity, she unpacks the solace of solitude, the courage to live unresolved mysteries, and the simple keys to her own version of “the good life.” Whether you’re a longtime admirer of Maggie’s work or being introduced to her poetic wisdom for the first time, this conversation is a masterclass in beauty, truth, and the regenerative power of vulnerability.

You can find Maggie at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Liz Gilbert about writing yourself letters from love.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

photo credit: Devon Albeit Photography

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Maggie Smith: [00:00:00] You get to a certain age where you know who you are, and you don’t have to apologize for that or feel like that’s even required. Like, I understand, too, that my perspective on things and my sense of humor are not everyone’s. When I’m writing, I’m not really speaking to everyone. I really want to think about the things that I’m making, becoming part of somebody else’s life. The best books, the best songs, the best poems are sort of lenses that once you’ve spent time with them, you view the world and your experiences differently. After you’ve read it, it becomes this lens that you see things through and it changes you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:46] So what if a poem could change your life? Have you ever read something that felt like it literally cracked your world open, giving words to experiences that you thought were unutterable? My guest today, Maggie Smith, she experienced exactly that, but not as a reader, as the writer of the poem Good Bones. After being rejected by many journals, the poem was eventually published online and quickly became this global phenomenon. Her life would never be the same, but in so many ways she never saw coming. Maggie is the renowned author of multiple best-sellers and award-winning poetry collections, with work appearing in top publications. In her memoir, You Could Make This Place Beautiful, which I loved, Maggie just unflinchingly explores the disintegration of her marriage, contemporary womanhood, her renewed commitment to herself, really weaving together snapshots of life with meditations on secrets, anger and narrative itself. In this deeply honest conversation, Maggie shares how, in the early days, music actually became her first poetic teacher, allowing her to transcend the constraints of plot and really distill pure experiences into lyrical language. And we explore the fateful chain of events that led to Good Bones and the publication that captivated millions during a collective moment of trauma and suffering. And Maggie doesn’t shy away from the contradictions in her path. We dive into how Mega-success also revealed chasms in her marriage and life, how she leaned on art to help metabolize hardship and the liberation in embracing life’s unanswerable mysteries.She offers insights that will really resonate with any creative soul who is grappled with the complexities of success and relationships, and honoring their truest self. She unpacks the solace of solitude, the courage to live unresolved mysteries, and the simple keys to her own version of the good life. So whether you’re a longtime admirer of Maggie’s work or being introduced to her poetic wisdom for the first time, this conversation is a true exploration of beauty, truth, and the regenerative power of vulnerability. So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:03:10] So excited to dive in. You know, I was reading a recent post of yours, I think just in the last couple of days where you were talking about the origin story and how when you were a kid, very introverted, hanging out in your room and music really became something that was deeply meaningful to you. And you even describe it as sort of your your first poetry teacher. And it fascinated me because I feel like when you read your writing, whether it’s poetry or, you know, the recent books, everything that you do is so lyrical. And I’m wondering if you feel like that’s really informed by a deep love of music from the time you were a kid.

Maggie Smith: [00:03:44] You know, I think so. You know, I read mostly fiction when I was a kid. I think most of us do. You know, I was reading, like, Nancy Drew and Trixie Belden in The Boxcar Children and Fairy Tales and really anything I could get my hands on. And a lot of them were adventure books without parents present, which, like, that’s the key. If there are parents around, nothing good ever happens. Nothing exciting anyway. But the thing about all of those books is that they’re plot-driven, right? So you have like characters in a place and there’s usually some sort of like exciting conflict, and then something has to happen and then it gets all sewed up at the end. And that’s not the way my brain works. I’m not really a plot person. I’m much more. I say I’m kind of more of an image presenter or like an experienced distiller more than a storyteller. I would much rather spend time describing something in great detail, and maybe making a metaphor to explain what it reminds me of, or what I think it’s related to or connected to, than having person A say to person B something and then they go to another location. And for me, music was one of the first experiences with language that didn’t require plot. Um, you know, like nothing had to, quote-unquote happen in a song. Like, it could be you were sitting in the sunshine thinking about something or remembering something. I mean, so many of those great 60s 70s singer-songwriter lyrics from my parents record collection. There’s so much nostalgia and also like good time songs like I’m on the Road and I’m Looking Out the Window and I’m seeing this or seeing that. And so I think for me, music, it just gave me permission to use language in a different way than I was finding in the books I was reading.

Jonathan Fields: [00:05:41] Yeah, I mean, that makes so much sense, you know, because music especially sort of like the classic singer-songwriters, you know, like Joni Mitchell, uh, Neil Young, Dylan, like that whole sort of like generation. It was really more vignettes than stories. When you really think about it, you know, it’s sort of like these passing glimpses of a moment. But I think what’s so powerful about that also, and we feel like we actually have to have a story almost, you know, spoon-fed to us with all the details for us to transfer into it. But it’s almost like the deletion in a vignette allows you to fill in the blank spots with your own experience. And I feel like your writing does a lot of that too.

Maggie Smith: [00:06:16] Oh, that’s so kind. Thank you. I love that idea. As a writer, regardless of the genre I’m working in, I’m always thinking about how not to sort of close every window and door, to leave some openings for the reader to get in, because really, a piece of writing isn’t finished. And I think this is true of music, too. It isn’t finished until it has a reader or a listener like it’s we are participating and sort of co-creating this thing. I make it and I hand it to you, and then you bring all of your life experience and emotional intelligence and associations to bear on the thing I handed you, and it becomes something different in your hands than it was when it was just me doing it by myself. And if I’ve sewn everything up so tightly that you can’t find a way in, it’s sort of like I’m not really holding up my end of the bargain.

Jonathan Fields: [00:07:14] Yeah, I mean, that lends actually really powerfully. It actually, a couple years back, uh, I was having a conversation with Kate DiCamillo, children’s book author. She said nearly the exact same thing, but with kids books. Also, she’s like, literally the final act of of, like, writing and publishing. This book is getting into the hand of a child, into the mind of a child. And it’s they’re reading that sort of like completes the cycle, which is kind of fascinating.

Maggie Smith: [00:07:36] Yeah, yeah, it’s really not done. Like when we think about, you know, stages of the writing process, I mean, the last one is like, you know, revision, editing, publishing, but there’s like this whole other thing that happens afterwards is not really so delineated, and it’s the connection that you get to make with someone else. And I don’t know, for me, it’s in some ways one of the most gratifying and also most terrifying parts of the process. Writing a book is one thing. Handing it, you know, kind of kicking it. Out of the nest and handing it to other people is something very different. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:14] I mean, that brings up another curiosity of mine. I know you sort of shared in different ways in different times that, you know, you definitely see yourself on the introverted side of the spectrum. And yet you write in a very publicly vulnerable way. And I’ve often I’ve wondered how that lands with you.

Maggie Smith: [00:08:30] It’s not always easy. Yeah. I mean, there’s sort of a joke in my family that of all, like, I have two younger sisters and of all of us and my in my immediate family, I was the most introverted. I was the sort of room dweller, the opt outer non-joiner. And I had sisters who were like athletes and doing show choir and, you know, just it was very different. And it’s kind of funny for everyone, including me, that I’m the person who now has probably the most public job out of all of us. I think one of the deep ironies of writing is that many of us get into it because we are introverts, and we like spending time with our own thoughts and our our records and our books and our sketch pads. And then if you do enough of that, and if you find a readership, it requires you to sort of shepherd these things into the world and get up in front of people and talk and get on an airplane and go someplace and, and do a lot of a lot of things that are more exposing and can be uncomfortable. But that’s that’s part of the that’s part of the gig. So I guess I hope my fear of it, which has not gone away, keeps me honest. You know, like there’s just no way I’m going to become a game show host. I do it because it’s part of getting the work to other people. But I could also live in a cabin in the woods and not speak to other people and be just fine.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:03] I’m pretty much right there with you, actually, so. But it’s such an interesting dance, right? Because, you know, if there’s a side of you that that has figured out some kind of work that you really love doing, that really lets you feel fully expressed, and then you have an opportunity to actually, like, share that with the world and have people receive it and support it and support you in turn. Yeah, it’s this fascinating dance, you know, because if you don’t actually need that on a sort of psycho-emotional level and actually you probably prefer not to have it or at least have have some pretty serious boundaries up there. But you also see that it’s enabling you to do this other part of you that really makes you feel more whole. It’s such a fascinating dance. It’s something I grapple with on a pretty regular basis too.

Maggie Smith: [00:10:44] Yeah, it’s funny, I was visiting with some high school students recently because I’ve been doing an artist-in-residence program at a museum here, and we’re all gearing up for this final end-of-year open mic. And for some of these students, it’s like the first time they’re ever going to stand up at a microphone in a big room and read something, you know, read something that they wrote that’s vulnerable. We had this meeting and I gave them a pep talk about the value of sharing, and part of it is that part of it is what you say, like, this is what it takes to do my job. So I have to find a way to do it my way and make it work for me. But the other piece of it that I shared with them is like, you know, I said, how many of you listen to music today or read a book in the last couple of days, or watched a movie or TV? And of course, everyone raised their hands just with the music. And then I said, well, what would have happened if those people had been so shy or scared or reticent that they didn’t put that thing into the world? I mean, it wouldn’t have touched your life. And that’s part of it, too, is is like we kind of have a responsibility to one another. And if I make something and I think it might have the capacity to mean something to somebody else, then I feel a kind of like community responsibility to not like, hoard that thing. And I was telling them the same thing. Like, you don’t know how far the ripples might go. Something you read in that room might touch someone and you might never know. They might not even have the guts to come up and tell you that they had that same experience, or that it meant something to them. But we have to trust when we send things into the world, that they’re reaching people that we may never meet.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:34] Yeah, I mean, that must have been so interesting with are these, like high school-aged kids? Yeah. Yeah. To sort of like have that conversation with them. But also getting back to your earlier point, how do you then also let them know that even if you have the courage to stand up there and say this thing and speak your piece and express what’s deeply vulnerable to you, whatever it means to you, it’s not going to mean to everybody else in the room. Yeah, and they’re going to have their own interpretation. And sometimes it’s going to be really different than what you your own like sort of like internal meaning was. And that you’ve got to almost like the minute you speak it out loud or the minute you surrender to the public. It really is an act. To surrender. It’s like it’s as much theirs now as it is mine. Which for any grown-up, I mean, like, I’m. I’m Gen X and I struggle with that all the time. I’m like 16, 17, 18-year-old kids. Like, it’s got to be tough.

Maggie Smith: [00:13:20] Yeah, I think so. And it’s true. Like, you know, my position basically is when I let something go, when I say it’s done, I’m no longer seeing things I want to change. I’m no longer dissatisfied with it. And I let it go, or the deadline just comes and it’s just time and I let it go. It’s none of my business what other people think of it. Now. That’s easier to say than it is to actually live by sometimes. Like no one wants to get negative reviews, no one wants to be trolled on the internet. I mean, it’s it’s always nicer to get kind feedback or at least feedback that you think is in the spirit that you intended when you made the thing. But that’s not always going to be the case. And so you’re right. You have to kind of serenity prayer that thing right, and just let it go. And instead of worrying so much about what the reception is for, the thing you just made the best cure for that anxiety is just start making something else, you know, and let it go.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:25] Yeah. It’s interesting. You know, I think we get so precious about the creative process and we don’t own that. You know, to a certain extent, this is a volume game and not just to perfect your craft. Well, you’ll never perfect your craft not just to work on your craft, but like you just said, also, it’s sort of like it gives people something else that you’re sort of like releasing, and then it’s like you’re not judging all of the feedback and all of the moment by this one thing and then saying, oh, it was terrible. Never again. You’re just saying, I’m going to keep putting things out and some will end and some will won’t. And but at least there’s a quote, a body of work rather than this one thing that you can kind of diversify the experiences around.

Maggie Smith: [00:15:03] Yeah. That’s true. I mean, I think if you make a lot of different things, somebody’s going to like something.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:09] Right. Hopefully, right?

Maggie Smith: [00:15:09] Let us hope. And yet if you had 500 really nice comments and five snarky ones, the five snarky ones will live rent-free in your brain on repeat until you die. I mean, that’s just sort of how we are as humans. I think it’s hard to sit with negative feedback. And so it’s it’s good to remind ourselves that, like, we just keep going. We make other things. I say all the time, I’m not for everyone. My work’s not for everyone. I’m not for everyone. My music taste what I like to eat. My sleep schedule like I’m just not for everyone. None of us is. And if we try to be everything to everyone, we will have sort of diluted ourselves down to some unrecognizable form.

Jonathan Fields: [00:15:55] Yeah, and I love that. And it is really hard to stand in that, you know, it’s when you read your writing in particular, there’s always this sense of it’s not overt, but almost like implicit gallows humor in it.

Maggie Smith: [00:16:07] Oh yeah. That’s that’s Gen X, right?

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:09] Sometimes. Right. I’m like raising my hand. Yes. Disaffected. All this, all this stuff. And you seem fairly fearless about just sort of like saying, this is how I see the world, and it’s going to enter the way that I express myself, and I’m good with that, even if other people aren’t. I’m wondering if that’s been a process for you.

Maggie Smith: [00:16:25] I don’t know that it would be safe or accurate to call me fearless in any situation. I am definitely not fearless, but what I have learned to do is do it anyway. Like, oh, I’m scared I’m doing it anyway. Or if I’m really too scared to do it, I will find some workaround that allows me to do x, Y, z and not do that thing that is just too terrifying for me to do. But I almost never say no out of fear. Like that’s not a good enough reason for me. I don’t mean endangering my physical safety, but if I’m presented with some sort of opportunity or challenge, if the only reason I’m tempted to say no is because I’m afraid of failing or embarrassing myself, or being disliked, like those aren’t valid enough reasons to not lean in and try unless it involves public speaking, in which case I can find it. I can find lots of reasons not to do that. I’m like, oh, I can’t get away. I’m a single parent. Um, but yeah, I’m not at all fearless. I think I just, you know, you get to a certain age where you know who you are and you don’t have to apologize for that or feel like that’s even required. Like, I understand, too, that my perspective on things and my sense of humor, again, are not everyone’s. When I’m writing, I’m not really speaking to everyone. I sort of imagine, I think, a kind of single human being who was my ideal reader, who gets it.

Maggie Smith: [00:18:04] And I think if I if I thought about. Readership as like potentially millions of, you know, faceless human beings. I think it would be really hard to let go of things, because that doesn’t feel like it has the potential for a warm reception or even real human connection, which I think is what we want when we make things and hand them to other people. Like, I don’t want to do like a t-shirt cannon with my work, where I’m just sort of like shooting it into like a hockey stadium and maybe somebody gets one. I really want to think about the things that I’m making, becoming part of somebody else’s life the way that, like all the books and the room I’m sitting in now and all the records and the room I’m sitting in now are part of my life. The best books, the best songs, the best poems are sort of lenses that once you’ve spent time with them, you view the world and your experiences differently. After you’ve read it, it becomes this lens that you see things through and it changes you. It doesn’t matter if you read it once or if it’s a book you’ve dog-eared and you come back to again and again, and there’s no getting to that kind of intimacy with a reader via a t-shirt cannon approach.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:28] Yeah, no, I completely agree with that. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. 2015. You write this poem Good Bones. From what I understand, it takes about 20 minutes to write this thing. It kind of channels out of you. You spend a chunk of time after that, submitting it around, trying to get it published. Nobody’s taking. Then finally in 2016, somebody says, yes, this goes online. And this becomes for so many people, for millions of people, what you just described those books and those albums were for you. This becomes a moment in time, like an inflection point where they experience this poem, and this is pretty concise poem. It’s a short and sweet poem, but they experience the world and they experience their lives differently after it, and that leads them to share en masse. And this is a crazy, crazy, crazy wild. And I want you, I want to talk a bunch about sort of like, you know, how that then became this before and after moment for you as well. But I’m also curious because I’m always fascinated by the concept of sliding doors. You know, there’s one thing slightly differently. You write this in 2015, you’re submitting it around, hoping somebody’s going to publish it, that it goes out there in the world. It doesn’t. It’s a year or so later when it finally lands, when it lands. Also, it is a moment in our collective history when there’s a lot of trauma in the air. And I wonder if you ever think about, you know, what things have unfolded differently in terms of how this was received. Had somebody said yes, like right after, you know, like we’re submitting around in 2015, a year before?

Maggie Smith: [00:21:02] Yeah, I mean, I wrote the poem in 2015 and started submitting it to primarily print magazines, print journals, and it got rejected a few times and then got taken by an online journal. I think it was still late in 2015 that it was taken. But then publishing is such that they slayed it, you know, six months ahead. So I kind of forgot about it. And it came out in June of 2016. At this time when all of these terrible things were happening. And yes, of course, I mean, I think it was sort of a perfect storm of it was a short poem that you could get the whole thing in one screenshot. So it was perfect for like Twitter, Instagram. No, I was not thinking about that when I wrote it. No one, I think, plans for a viral poem, or certainly I was not planning for a viral poem in 2015. I was parenting a, you know, a three-year-old and a six-year-old and just trying to get a little something done in the evenings after they went to bed.

Maggie Smith: [00:22:01] And it has definitely occurred to me that if one of those print journals, you know, prestigious print journals had said yes, it would have landed in a wonderful place, that I would have been really proud of having it, but it wouldn’t have gone viral. Probably not that many people would have read it. Print journals tend to have fairly small. It’s. The readership is not giant for print journals. That’s poetry. Or even if the poem had been two pages long and been published online, and you hadn’t had to kind of scroll through a couple screens, even if it had come out that week, I don’t think it could have happened. So it was it was sort of the message of man, the world is a is sometimes a really terrible place, but we have the ability and also the responsibility to do better. The message, the timing, the length and the fact that it was on the internet. I think all of those things had to kind of align at the same time for it to go as viral as it went.

Jonathan Fields: [00:23:07] Yeah, no, that makes a lot of sense. And by the way, for the three people who haven’t read it yet, we’ll drop a link in the show notes so you can quickly read it and understand what we’re talking about. And I think probably see why it was just so deeply resonant for so many people in that moment. You know, publicly it landed in this really powerful way, but also this became what you described as a lightning strike moment in your own personal life. On the one hand, you’ve got this amazing thing. You’ve been a writer for a long time, a poet for a long time. You have a lot of stuff, like you’re raising two kids, you know, like you’re married and you’re trying to just make everything work. And this one thing just creates profound change. But like so often happens, you know, when somebody says, is this a good thing or a bad thing?

Maggie Smith: [00:23:50] Both. Yeah, both. Yeah. It’s funny, I’ve thought a lot about that too. And I think there are some growth moments that we can have, like particularly professionally, that can impact our marriages, our relationships, our lives. And a lot of times we can prep for those, you know, like, I’m going to go up for partner or I’m going to go up for tenure or I’m going to go up for this promotion, or I want to apply for this position, which means we’re all going to have to move. And those kinds of situations give families time to talk and plan and sort of like argue or recalibrate or say, no, that’s not going to work for me, or who’s going to pick up the slack and who’s going to drive. The soccer practice. If you’re doing X, Y, and Z, and having a poem go viral overnight is not one of those things. There was no planning for it. And so it was a really wonderful lightning strike for me as a poet and a really problematic lightning strike for me as a wife. And so, yeah, I write about it in my memoir that there’s a kind of like line of demarcation that I don’t know that I was so aware of it at the time, because so many things don’t really become clear to us until later.

Maggie Smith: [00:25:12] But like looking back on that, I can see that that was a real turning point in my marriage. And I think sort of like the perfect storm of the poem going viral. It also took a perfect storm of various factors to lead to the end of my marriage. But that poem going viral is one of those factors. I don’t want to blame the poem because it’s not the poem’s fault, right? And it’s not my fault for writing it or publishing it, and it’s not reader’s fault for sharing it on the internet. It’s not Meryl Streep’s fault for reading it at Lincoln Center. It’s it’s not anyone’s fault. But it was something that created strain. And and like once that starts, it’s like one little crack can make another little crack, which can make a bigger crack, etc., etc., etc..

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:04] Yeah. And you write about this so powerfully in the book, you know, and on the one hand, all these things you’ve been working for so hard for so many years, it’s all happening, you know, and it’s happening like you just said, there’s no prep. Like you wake, you open your eyes one day and you’re like, oh wow. Yeah, life is different and doors are being opened that weren’t open before and all sorts of things come tumbling towards you on a professional level. And part of that is also you have the opportunity to then be out on the road a lot more than you had been in the past. And I guess the blend of this, it ends up bumping up against a long-time marriage where certain patterns were just like ingrained. Certain assumptions about how things would be had been laid over a period of years. And those all get blown up and again, without any there’s no ramping time here.

Maggie Smith: [00:26:51] No, no, there was no time to onboard to any of this. No, it really did just sort of blow up overnight. And then the choice becomes like, well, do I turn down all of these opportunities because I’m the stay-at-home parent, or do I rally babysitters and grandparents and my spouse and try to lean in to my professional life in a way that I really hadn’t been able to to that point? And I wanted to lean in, and I don’t regret it. It took me a long time to get there, but ultimately I realized, like, if your partner isn’t excited about opportunities that you’ve worked hard for over a long period of time and isn’t excited enough to adapt and sort of like be in there with you, if it’s more about an inconvenience than it is about the opportunity, that’s probably the death knell. There’s no negotiating. Like it doesn’t matter how many babysitters you have. If that’s, you know, as my daughter would say, the vibe, it’s interesting.

Jonathan Fields: [00:27:59] I remember, um, years ago sitting in a small gathering and there was a panel up front and they were talking about relationships in business partnerships. And these were, you know, like big fancy people talking about all sorts of fancy stuff. And one of them said, you know, almost anything is recoverable, almost any type of emotion or feeling between people in relationship. And he was talking about business, but it really applied to like any relationship. Is it recoverable? He said. But there’s one that I found I’ve never been able to see somebody recover from it. And he said, it’s contempt, and it’s like once that enters into it, not that it’s impossible for everybody, but it’s just that’s one of those things where it’s like someone dropped a bomb in the middle, and it’s really hard to put the pieces back together and again in a way that forms the shape of a relationship. And it sounds like that’s kind of like exactly what you’re experiencing.

Maggie Smith: [00:28:47] Yeah, I’ve heard the same thing. And I think that’s I think that’s true. And it makes a lot of sense. Like there are a lot of things that you can negotiate, but if someone doesn’t, if you don’t believe that the other person wishes you well, it’s a nonstarter. I mean, it’s just a non-starter. Like, yes, it is not easy when somebody has to work late and somebody has to do bath time and dinner and bed, and you have small kids. Yes. It’s not great when you’re having to negotiate work commitments and preschool pickup, etc., etc. but I think when you wish someone well, you find a way to make that work. And when you don’t, it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter what the logistics could be.

Jonathan Fields: [00:29:32] Now that makes a lot of sense. You write that your then husband. It literally said, like, don’t travel in service of your writing anymore. And of course like that. Those may have been the words on the surface, but what was implied underneath that it sounds like, was, you know, it was a really evaluate. It was an evaluation of the relative value of each of you in this relationship.

Maggie Smith: [00:29:54] Yeah. I mean, I think it’s tricky for those of us who make a living as artists, we’re probably outearned by our partners or potential partners. Right? If you have one spouse who’s a poet and one spouse who’s a lawyer or a doctor or an accountant, you’re never going to win the argument. If the basis of the argument is who makes more money? Therefore, whose time is more valuable? There’s no way I could win that argument. For me, it was never about the income. It was about being able to sort of live more fully this life that I’ve worked toward for a really long time, not accepting a net loss, but but realizing that it would take sacrifices. And yes, I was the lower earner in the family. And and I do think, I mean, a lot of the patterns that I willingly sort of adopted from my own upbringing. It was really traditional. Um, and I don’t know why I didn’t seek it coming that that would not work. Like, I sort of took my parents’ marriage as like a template or your Gen X, so you’ll remember this like a transparency, you know, that the teacher would lay on the little light thing to write on. I sort of laid the kind of upbringing I had, like a transparency over my own life, which looks nothing like this. I mean, I went to grad school, I was publishing books, I was raising kids, I was traveling and teaching. It was not the same life, but somehow I thought I could be the same wife and mom, and I couldn’t. I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t do the same thing.

Jonathan Fields: [00:31:39] Yeah, I’ve heard you say if I folded myself up so small, I don’t know where to find myself anymore. What model is that? And that was in reference also in terms of the model of how you’re living your life, but also how we show up as parents, right? Yeah. I mean, any parent knows kid really doesn’t listen to what you say. They watch what you do.

Maggie Smith: [00:31:58] Yeah, they watch what you do.

Jonathan Fields: [00:32:00] Right. And that’s the entirety of the lesson. And it’s so it’s so interesting when you find yourself in those moments because you’re like, huh, what am I inadvertently transmitting to these little beings who I really want to have the best opportunity to live fully in the world?

Maggie Smith: [00:32:13] Yeah. I mean, both my daughter and my son. It struck me, you know, fairly early on in the process of everything unraveling that if and I did for a time agree not to travel and kind of make that part of my life very small in order to make it work. And at some point I thought, this isn’t going to work in the long term and not for me. I’m going to be miserable and resentful because I’ve been asked to make something that means so much to me, tiny, in order to accommodate the sort of family schedule. But it’s also not going to work for my kids. Like, what am I modeling for my children? I’m showing my daughter that that women are service providers and should subsume their lives to the family as if it’s 1955 and I’m showing my son what expectations he should have of a partner, whatever gender, someday. And I didn’t want either of them to grow up fearing what marriage and children might do to them. In the case of my daughter, and how limiting it could potentially be. And I didn’t want my son growing up feeling entitled because he’s witnessed like, oh, this is what happens. And then the mom compromises so that she’s always around. It didn’t seem healthy for for either of them to see that happen. And so now they live with me. I’m gone. Sometimes there’s a sitter here when I’m gone. I just got back from writing in a cabin for two days. There was a sitter here. It was fine. We text, but they see what I have to show for it. And they come to events and they. They see the books on the shelf, and they know how much I love my work. And they also are with me sometimes at the farmers market, when random people come up to me and say, oh my gosh, your book got me through the toughest year. And so I don’t know how much of that they’re absorbing, but I hope some of it, you know that. I hope it feels okay to them.

Jonathan Fields: [00:34:16] Yeah. I mean, just the notion, you know, that you’re transmitting to them just by the way, that you’re showing up, that you can be in the world in a way which is truly nourishing and that they’re you don’t have to leave parts of yourself off to the side. Yeah. Because there’s so many messages that kids get now that say, no, conform, conform, conform like. We just want to fit in. You know, you hit middle school and it’s just please, please don’t leave me out. Like that is everything. And so many of us never leave that mode. We just kind of assume that this is the way that we have to be to be able to breathe as we move through life, which means we just we’re constantly like, lopping parts of ourselves off and leaving them, you know, out of the room and wondering why we’re never okay. And like what you’re saying is now I’m going to show up like all of me is worth it. Showing that, I mean, not just, you know, to your kids, but also I wonder if there was a certain amount of just internal rewiring yourself, like in reclaiming that.

Maggie Smith: [00:35:12] Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think once the sort of like extreme grief, I’m laughing. That’s the gallows humor. Once I sort of got off the floor after my divorce, I was like, oh, I can do anything, really. I mean, that kind of life shift is terrifying and continues in many ways to be terrifying. Like, I’m the one steering the ship. That’s that’s scary. But it’s also really exhilarating to just to be, you know, I’ve said it’s like it went from life, went from being like a group project. And we all know how those projects go in school. It’s like one guy just like buys the poster board. Okay. That tells you that I went to school in the 80s. Now it’s like all it’s like all Google Slides. So who am I kidding? There’s no poster board, there’s no diorama. But you know, I hear my kids complaining about group projects all the time. It’s like, well, I want to do this, but so and so wants to do this or I’m I’ve prepped so hard and this person isn’t even really they’re kind of phoning it in. That can be really hard in your personal life too. And the one thing I’ll say about being single and living alone, although it’s a group project because I have two children and a dog in my house, is I get to just do things my way and not as a tyrant, but it’s just like, do I want a yellow couch? I do, I’m going to buy a yellow couch. Do I want to play the Clash really loud while I cook dinner? Yes I do, I’m going to play the clash really loud. Let’s get pizza. Let’s do this. I mean, there’s there I really did have to kind of hit a reset button where I wasn’t considering what anybody else might think, say, judge, give me side eye for just sort of show up and be fully myself. Finally in my mid-40s. I mean it took long enough.

Jonathan Fields: [00:37:08] Yeah, I think for so many it never happens. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. Yeah, I’m curious about something else as well. And I’ve heard you speak about this. I’m wondering what your current thoughts are, which is this notion that, and I guess especially in the context of Good Bones, that you created something that was this really beautiful work of art that went out into the world and gave language to the experiences of millions of others. But a big part of that experience was suffering, loss, grief. And I’m wondering how that lands with you, knowing that you’re playing some role in the suffering of millions of others. You’re not causing it, but in giving them language on on the one hand that that does that feel incredible, but also does it feel a little bit weird?

Maggie Smith: [00:37:58] It feels incredibly weird. I mean, I, I have had such a complicated relationship with the poem Good Bones. You know, when it first went viral in 2016, it was the week of the pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, and Jo Cox had been stabbed to death in England. And she was the mother of young kids herself. Not that far from my kids age. And then with, um, Trump becoming president, I mean, there and then pretty much anywhere I’d go at any time if my social media mentions started ramping up, instead of being like, oh, great, people are reading this thing that I made at a coffee shop, I would think, oh no, what happened? And it’s a really strange thing to have your, you know, quote success or just your readership growing or people engaging with your work, being directly tied to tragedy time and time again, and particularly with violence. I mean, the Manchester concert bombing at the Ariana Grande concert I was at in New York City for a reading and my social media mentions started going wild and I thought, oh my gosh, what happened? It was the night before my book, Good Bones came out. My social media went crazy. It was the Las Vegas shooting from the hotel window into the concert. I mean, on one hand it’s like, boo hoo, right? Like I can’t complain. These things have not happened to me. And it’s it is a wonderful thing to have people finding my work and maybe finding their way from Good Bones to other poems, other books, other things I’ve made. But it is complicated, and it would probably feel less complicated if it were a poem that was about how beautiful the world was, and not how terrible it is to. And people read it at weddings, you know, and at confirmations or high school graduations or, you know, other kind of celebrations. And then whenever people were sharing it, I think, oh, a baby was born or someone just got married and it would feel like a celebration instead of, oh, no, what now?

Jonathan Fields: [00:40:19] Yeah. I mean, it’s so interesting. I think oftentimes we feel like we’re bonded as a culture around things that are elevating Emile Durkheim’s theory and collective effervescence. You know, like, we come together, we celebrate together, and this is how we form a sense of belonging. I’ve always believed that commiseration was an equal source of belonging. We don’t want to go there, though. We don’t want to have that conversation, because we don’t want to invite that, because that means that we’re like, there’s a level of collective suffering that bring us together. You don’t want to acknowledge it, let alone have a conversation about it. It’s interesting that you bring up the shooting in Vegas. I was actually there and I was in it. There was a weird similarity to what you’re describing because I was there to speak, to give an inspiring sort of motivational talk to a large room of like people who had worked for 15 years to become partner in this giant firm. It was a celebration. And this was the morning after the shooting in Vegas, and I walked down from where we were on the other end of the strip to where, like, everything was blocked off and everything was it was horrific, absolutely horrific. And I just stood there like for half an hour, like just unable to function or move or breathe. And then as I’m walking back thinking about like now my job is actually to to celebrate the fact that there are a whole bunch of people who are still alive and who have come and who have sacrificed so much to be in this moment in their lives, and I get to stand on stage and do this thing that I love doing and offer something. It was a really hard thing to do. Yeah, but I feel like, you know, we like to imagine that we live in a world of binary, but like, it’s all gray at the end of the day. And that’s so much of what you speak to in your writing.

Maggie Smith: [00:42:04] Yeah, yeah. It’s so gray or it’s, it’s just and it’s and ness. Right. Like it’s not like this is true, but this is also true. It’s like it’s everything all the time. Like beautiful, terrible things are happening all the time. They don’t take turns. That’s not. That’s not how it works. I mean, at the same time that that massacre was happening, beautiful things were happening, probably in the same city, on the same block. You know, people were hugging their children goodbye. People were, you know, having conversations with their mothers. I mean, it’s everything all the time. And frankly, I write poetry just to manage the everything all the time ness of the human experience.

Jonathan Fields: [00:42:48] Yeah. I mean, it sounds like in no small part also that the book was one of the ways that you were working towards trying to metabolize this big transitional window in your life at the end of the marriage, but also like the beginning of a whole lot of new things. Do you feel like you were able to through that process?

Maggie Smith: [00:43:06] You know, mostly. It’s funny, I sat down to write. You could make this place beautiful with a really naive intention, which is, I thought if I spent a whole year doing every day, just sort of every day writing about my marriage and the kids and sort of trying to piece it all together, I would have it figured out, like I would be able to sort of see very clearly, oh, that’s what happened. If that hadn’t happened, this wouldn’t have happened either. Oh, that’s where we first went wrong. Like, it was almost like trying to retrace the breadcrumb trail and, and get back to a safe place and Hansel and Gretel and that I couldn’t do. I mean, it’s sort of an unsolvable mystery in that, again, there’s too many factors and and too many other people involved for me to be able to say, well, I know for sure why this happened, how this happened when this happened, and that there could have been no other way. So it didn’t solve that for me, but it definitely helped me metabolize the experience. I don’t know what I think until I write it down. That’s maybe unfortunate for you because I’m talking to you verbally right now, so I may change my mind about everything I’ve said once.

Maggie Smith: [00:44:27] I once I write it down, but I, I do use writing, not as therapy. I don’t find it necessarily therapeutic, but I think it’s really satisfying to take a kind of amorphous idea or experience or feeling that’s sort of swirling around in my mind, and to give it a form, to give it shape and to, frankly, just simply put it someplace not in my head. And so the shaping of the memoir and the telling of the different stories and the playing with the different questions and the going over the various metaphors for the experience, all of that collectively helped me feel more at peace with what had happened by the time I finished the book. And then again, because we were just saying the publishing process doesn’t end with publishing. You still have to get it to people. The past year of being with this book in the world with others, and hearing other people’s stories, getting mail from other people, getting DMs from other people, hearing how it’s touched them. That has even added like a different level of metabolizing for me. And if I had any doubt about the sort of value of undertaking such a vulnerable writing project, it was completely dispelled after, like email three from a stranger.

Jonathan Fields: [00:46:01] Yeah, you use the phrase unanswerable mystery, and I know you’ve used the phrase unanswerable question also. Um, and it’s interesting because, you know, you write a book like this and it almost like, well, what’s the resolution? Let’s solve the problem. Let’s get to the answer. But the notion of intentionally identifying unanswerable questions and then spending a lot of time really dropping into them, knowing from the beginning that this is actually not about the pursuit of the answer because it’s unanswerable. It’s, on the one hand, really hard to wrap around, like, how could you spend so much energy doing this? But on the other hand, it’s like, but isn’t that the marrow of life?

Maggie Smith: [00:46:41] Yeah, it’s not just this book, it’s life. I mean, the material of life is unanswerable questions or, you know, they have answers, but they have many answers that change from day to day, situation to situation. There are so few absolutes, and that is not something I think I would have said 6 or 7 years ago. I would have said, oh no, I know who I am. I know the kind of life I’m building. This is the way we do it. I think I was a lot more, uh, sort of structured and binary, even in my own thinking. Before my life imploded. It’s. It’s funny how your life imploding can help you see the ways that you were probably not thinking correctly about things in the past. But you’re right. We don’t know. We just do our best every day. I try to do as little harm in the world as possible, to leave it a little better than I found it to be compassionate, to raise my kids well, to right things I believe in, to take care of others. And I don’t know where that all leads, but we’re all just doing our best.

Jonathan Fields: [00:47:53] Yeah, it seems like you have been on this bullet train for a number of years now. And like we said, is it a good thing or a bad thing? It’s a thing. Yes, it’s a thing. Yes. And right. Oftentimes I found that when I’m especially when I’m talking to folks who sort of like they’ve been on a rocket ship and, and it’s been a number of years now, um, with all the amazingness that goes along with it. There’s also often just a profound tiredness. And I think we like to overlay, oh, best years of her life. And she’s doing amazing and creating great work. And like, yes, there was hardship, but she’s quote past it now I wonder from the inside looking out what your experience is around balancing the amazing parts of what’s going on and also a need for stillness and rest?

Maggie Smith: [00:48:38] Yeah, that’s a great question. I mean, I, I have been well aware since I was a young person, the amount of solitude I need is more than the average person, and I don’t I don’t know if that’s like a writer thing. I don’t know if it’s an introvert thing. I don’t know if it’s a Maggie thing, but I need a lot of time by myself, and I need a lot of time when I’m not on. That’s another thing. So if I if I am on for two hours, I need to be off for like six, then I can be on again. And so yeah, it’s funny, one of the most challenging parts of of having work in the world and having it be sort of warmly received is the oddness, the oddness that it takes. And it’s it’s wonderful. And I, I actually really enjoy it when I’m doing it. And then I realize I feel like I’ve been hit by a bus.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:35] Yeah, it’s the introvert.

Maggie Smith: [00:49:37] Yeah. I get back to my hotel room and I’m like, room service. No, I don’t want to have dinner. I just need to sort of go underground and put my headphones on. And, and so I think I have been smarter, particularly in the past 3 or 4 years, about being very realistic about what I need and not overscheduling myself, not pushing myself too much and like setting boundaries around my time like, no, I can’t do five things in one day. Like maybe some other person could do five things in one day and and be fine at the end and have that dinner and do the whole thing and then go for the drinks after. I’m just not that person. And it’s not because I don’t want to be that person. I think when people do that and make it look effortless, I, I’m like, oh, that must be fun. But no, I’d like to be in bed by ten and uprighting alone. I mean, I just said, I got back from a cabin in the woods for two days, I. Single parenting means you don’t have a whole lot of time alone, except for when the kids are at school. I love it when they’re at school. Summer is coming, and it’s going to be the three of us in this house. We don’t do camps, we don’t do anything. We travel together. So it’s going to be like two and a half months of like intense social, social stuff. And I will probably need to put my headphones on and go for some pretty long walks during during the summer months.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:07] Yeah, I’ve heard you say that your biggest wish is how do you get to peace? How do you get free? Is that it for you? I mean, it kind of comes full circle to the beginning of our conversation. Also, it’s solitude. Music, writing.

Maggie Smith: [00:51:19] Yeah, honestly, that’s all it takes. I’m actually like quite a cheap date. Like, I really I don’t need any fancy things if you give me. I mean, I used to tell my mom when she went to the grocery store when I was a kid, my, you know, my sisters both played club soccer and it was, like, really expensive. And there was all this traveling and I was like, I’m cheap and easy. Just get me some legal pads and some pens at the Kroger. That’s really all I need. And to be quite honest, for the last 40 years, that’s what I need. I need paper, I need pens, I need people to leave me alone for periods of time. Good music, maybe a coffee, some dark chocolate. It really is not that difficult piece for me. Is actually very, very simple and therefore attainable.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:11] You and I are wired very similarly in that way, especially the good music and the dark. Chocolate are pretty critical actually.

Maggie Smith: [00:52:17] Yeah, I know. Again though, it’s not like it’s not a tall order.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:20] Yeah, no. Pretty straightforward. It feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Maggie Smith: [00:52:31] Oh. Be yourself. That’s what comes up. Be yourself. You know what? It’s not easy always. But it’s simple. Like telling the truth, right? And being yourself is, in essence, telling the truth. Just the uncomplicated truth of who you are.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:51] Mm. Thank you.

Maggie Smith: [00:52:52] Sure. Thank you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:56] Hey, before you leave, if you love this episode, Safe bet, you’ll also love the conversation we had with Liz Gilbert about writing yourself letters from love. You’ll find a link to Liz’s episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project, was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help By Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project. in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did. Since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor? A seven-second favor and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields signing off for Good Life Project.