Have you ever found yourself torn between standing firm in your beliefs and values, while still wanting to keep certain people in your life – even when their views profoundly clash with your own? Maybe it’s an extended family member who continues to spout offensive rhetoric you vehemently disagree with. Or a close friend who just can’t seem to evolve their thinking on a particular social issue that deeply matters to you.

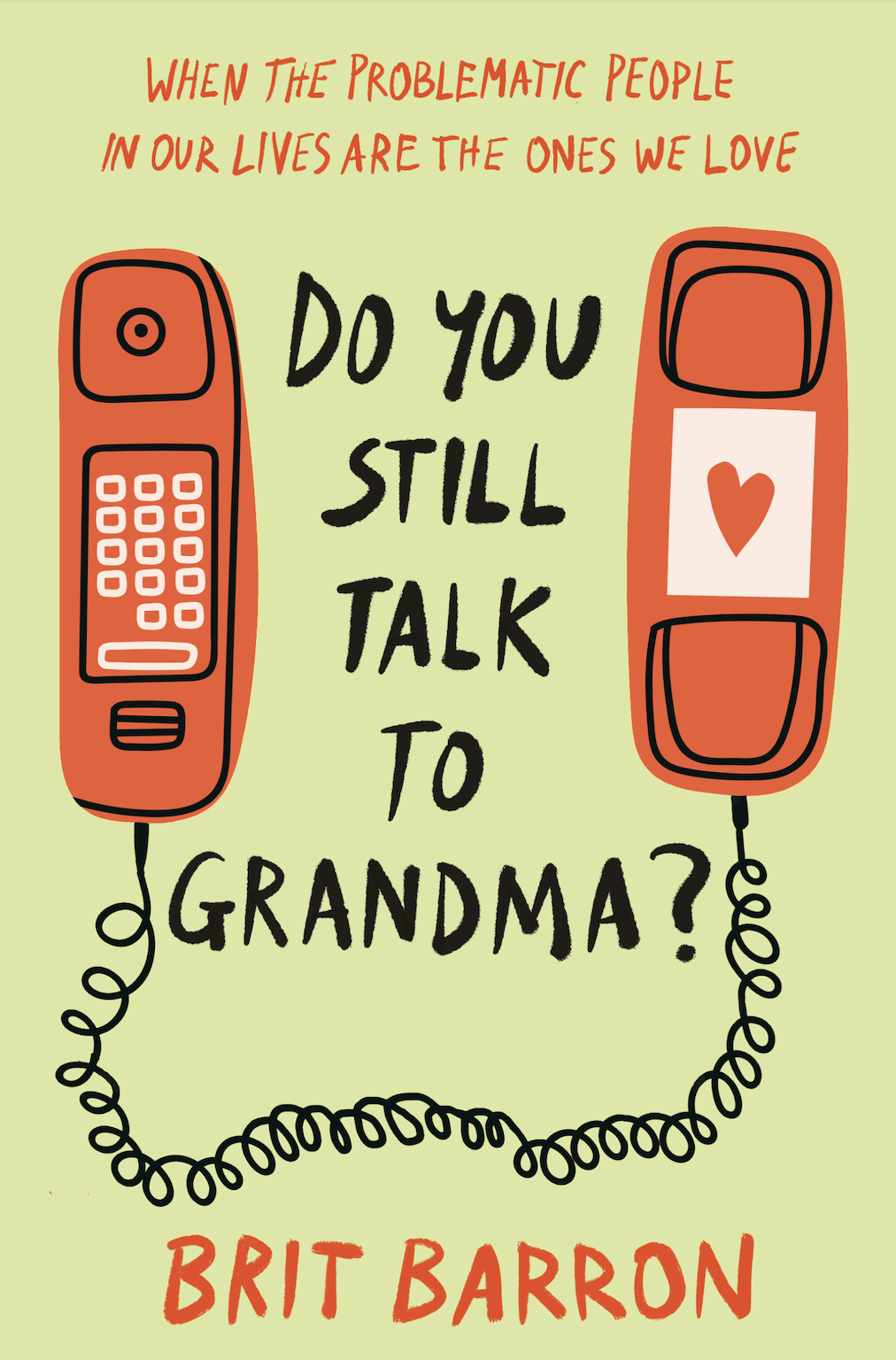

These situations force us to wrestle with challenging questions: How do we hold people we love, and have no intention of abandoning, accountable without completely writing them off? Is there space for redemption and reconciliation when the gap feels too wide? My guest today is Brit Barron, renowned speaker and author of the thought-provoking book Do You Still Talk to Grandma?: When the Problematic People in Our Lives Are the Ones We Love.

Barron dives deep into this universal struggle of how to navigate relationships strained by conflicting beliefs and backgrounds. Her ideas and personal journey have garnered national attention, making her a highly sought-after voice on the complex interplay of identity, spirituality, race, and human connection in these polarized times.

As Brit so powerfully conveyed, truly living with integrity doesn’t mean cold indifference or burning bridges when confronted with belief clashes in our closest circles. It means having the courage to stay present, to extend empathy, and to hold space for the beautifully messy reality that we’re all at different stages on our journeys of growth and evolution.

So imagine if you embraced the mindset of patient compassion the next time you found yourself at odds with a loved one’s unexamined beliefs or hurtful rhetoric. What if you led with the humble curiosity to truly understand where they’re coming from, before ever attempting to change their mind?

You can find Brit at: Website | Instagram | Episode Transcript

If you LOVED this episode:

- You’ll also love the conversations we had with Prentis Hemphill about finding wholeness in your relationships.

Check out our offerings & partners:

- Join My New Writing Project: Awake at the Wheel

- Visit Our Sponsor Page For Great Resources & Discount Codes

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Episode Transcript:

Brit Barron: [00:00:00] The farther we get down the road of polarization, the more that becomes true. Like, I only need to know one thing about you, and then I’ll know everything about you. It’s sort of how our brain works. And that’s also why cancel culture works on social media. I sell one picture and one lie and one caption. And that’s everything I need to know about who you are. And that’s a dangerous place to be, I think. But our ability to relate on a human level of understanding with how people have arrived at certain frameworks and certain behaviors, again, is going to do us a great service as we move forward in whatever work we’re trying to do.

Jonathan Fields: [00:00:36] So have you ever found yourself torn between standing firm in your own beliefs and values, while still wanting to keep certain people in your lives, even when their views profoundly clash with your own? Maybe it’s an extended family member who just continues to spout offensive rhetoric that you vehemently disagree with, or a close friend who just can’t seem to evolve their thinking on a particular social issue that deeply matters to you. It can even happen in work. These situations, they force us to wrestle with challenging questions. How do we hold people we love and have no intention of abandoning accountable without completely writing them off? Is there space for redemption and reconciliation when the gap feels too wide? My guest today is Brit Barron, a renowned speaker and author of the thought-provoking book Do You Still Talk to Grandma? When the problematic people in our lives are the ones we love. And Brit dives deep into this universal struggle of how to navigate relationships strained by conflicting beliefs and backgrounds, and her ideas and personal journey have garnered national attention, making her a highly sought after voice on the complex interplay of identity and spirituality, race, and human connection in these polarized times. And as Brit so powerfully conveys, truly living with integrity doesn’t mean cold, indifference or burning bridges when confronted with belief clashes in our closest circles, it means having the courage to stay present, to extend empathy when it’s appropriate, and to hold space for the beautifully messy reality that we’re all at different stages on our own journeys of growth and evolution.

Jonathan Fields: [00:02:16] So imagine if you embrace the mindset of patient compassion the next time you found yourself at odds with a loved one’s unexamined beliefs or hurtful rhetoric, what if you led with the humble curiosity to truly understand where they’re coming from before ever attempting to change their mind, or held that same humble curiosity and compassion out for yourself? So excited to share this conversation with you! I’m Jonathan Fields and this is Good Life Project.. It’s interesting. I feel like we live in times where there’s this feeling that so many people are walking on eggshells and We have an inner sense of what’s right and wrong, but in different contexts, in different relationships, whether it’s friends, whether it’s family, whether it’s work colleagues, whether it’s community, people are just really confused about how to respond to relationships when they feel like their relationships are in some way fraught or problematic, or the views that people are holding are really just not their views. And yet at the same time, they don’t necessarily want to jettison that person or feel like they can jettison that person from their lives. And you really dive into this. So I want to dive into a lot of the ideas around it. But I’m also curious, you know, this topic feels personal to you.

Brit Barron: [00:03:35] Yeah, it’s deeply personal. And the timing of the book releasing is interesting. But I’m sure, you know, as you know, that’s sort of a byproduct of just timelines and publisher calendars. And so this is actually a project I started working on back in 2021, and I sort of had multiple experiences in our time of having friends that people close to me sort of be on the receiving end of what we now so commonly know as cancel culture. Right. And and feeling sort of torn between these ideas of what do I do if people that I care about and people in my life make mistakes? Is there a way to sort of hold both to stand with integrity and the things that you believe in, and not to compromise that, while also acknowledging that everyone is at different stages of different journeys, and every relationship doesn’t have to necessarily be exactly where I am at the same time, because I don’t think that’s something I even want every single person in my life believe the exact same thing about everything I do. It doesn’t sound like a good time. So those sort of started some of these ideas of of working on this project.

Jonathan Fields: [00:04:47] You brought up the phrase cancel culture, which has certainly been a topic of conversation, I would say, over the last five years, six years in particular. Take me deeper into this, because it’s a term that we hear thrown around a lot. What’s your sense of what cancel culture is and isn’t? What’s really going on here?

Brit Barron: [00:05:03] I mean, I think we’ve seen it evolve in a sense, right? As the terminology became more familiar to us, and how I feel like it is just now is cancel culture sort of the blanket term we use for what happens when someone in a public sphere, which public sphere is a lot more wide now with with social media, everyone in a sense has an audience. It’s our reaction to that person no longer fitting into whatever belief or ideals that our group ascribes to. And I say our group because as someone who is more progressive and you would say, okay, this cancel culture only exists in this context, but it doesn’t. Right. You have sort of everyone and every group and every sphere of politics and society. They have their own group rules. And so cancel culture is a result of people sort of stepping outside of that. And then we we unleash all of our wrath on them. What I think is actually happening, and what I think is behind a lot of cancel culture is I think that the internet, in particular social media, has given us a clean opportunity to sort of export our own emotional labor onto strangers in the internet. While it’s maybe hard to sit with some of the nuance of our own lives and beliefs and how they evolve and different levels and things we used to believe are scary, that’s actually really hard. What’s easy is saying like, oh, you did that. You’re out and on to the next right.

Jonathan Fields: [00:06:29] It is so interesting, right? Because we live in this moment where so many interactions happen in some kind of public sphere, whether that’s ten people in a local community group that’s online as a, as a group or something like that, or whether it’s thousands or millions of people. I’m curious what your take is on this also. Like, I find what’s fascinating about this phenomenon is it doesn’t often stay in that initial space. If there are affinity groups that have any kind of access to this space, whether, let’s say you have an Instagram account or a Facebook account or something like this, right? You know, it’s very easy for sort of like people outside of that space, groups and communities outside of that space, often to have some sort of exposure to it. So there can be the initial group, which maybe like you feel like there’s more opportunity to say like, hey, wait, wait, wait, not so fast. Let’s have an actual conversation about this. But then there’s this sort of like acceleration. There’s an amplitude effect of like a pile on of all these people coming out of the woodwork who you never knew, you never will know, and you never, like, thought that they would have any role in a conversation. And it’s something that I think we’ve never really experienced or like in our human relational condition before.

Brit Barron: [00:07:40] Totally. The feeling I always feel is like frenzied, you know, it’s sort of like there’s oh my gosh, something’s happening. We all need to sort of jump on it. And I think that does such a disservice to our own human growth and change and transformation. Right. So, you know, if the two of us are having a conversation and we’ve been friends, you’ve been in each other’s lives. I say something, you know, like, hey, Brit, walk me through. You said that because that doesn’t sort of align and say, well, something I believe, and maybe we’ll resolve it in that conversation. Maybe we won’t. Maybe we’ll pick it up again. Right? So we’ll have a thing. But you’re exactly right. What happens when things happen in social space? Maybe it is just a conversation of the two of us, but maybe it’s on a podcast. And now you have sort of people who maybe they had the whole context of the conversation. Maybe they didn’t. Right. But now they feel invited into the critique of that moment. It makes sense to me. One of the quotes I use in the book is from a man named Richard Rohr, and he always says, if you can’t transform your pain, you transmit your pain, right? And so if we’re all feeling like we’re walking on eggshells and we feel uneasy about our place in the conversation, of course we’re going to take the first opportunity to make sure, okay, get this off me. I’m going to put it on someone else.

Jonathan Fields: [00:08:50] Yeah. And you said something really interesting also, which is that this notion that it’s often easier for us to just basically like hit the button that says, no, you’re canceled, you’re out, than it is to actually say, let’s do the hard work of seeing if we can tease this out and understand it a bit more. So the default, I think, for so many people, probably me included, I think we’re all sort of like we’re all in and out of this mode, like no matter who we are is to just want to take the easy option out because we either feel uncomfortable with the hard option or we have no idea how to actually step into it.

Brit Barron: [00:09:25] Totally. And I think in some ways that’s fine, right? Okay. I’m following Michael Jordan on Instagram and he said something I didn’t like and I unfollowed him. It’s really no consequence to me or Michael Jordan. But the problem is I think what’s been hard is we have this way of operating on the internet that is very clean. It is very black and white, it’s cut and dry. But the reality is most of us exist in these real life relationships where, okay, well, now these people we’re talking about our cousins, our partners, our grandparents, our parents, our coworkers, our friends from church, whatever it is that we can’t just say like, oh, boo, you’re out of my feed. And so now we’re forced with, wait, I don’t know that I have like the tools or the context to navigate this because I’m so used to just clicking a button and something is is resolved.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:15] Yeah, I believe that, you know, social media is where nuance goes to die.

Brit Barron: [00:10:20] Totally.

Jonathan Fields: [00:10:21] And it’s interesting sometimes when you see folks trying to have a more nuanced conversation in that public way and on social media, when there are like factions on either side that don’t want it to happen, that just want to dig in and say, this is there’s no room for nuance here. There’s you’re either with us or you’re against us. And I can understand there are really big, important, divisive issues where people feel strongly, understandably so. And yet It’s really hard to ever find bridges or any sense of resolution or and this is I’m curious about this. And you write about this like the notion of cancellation in the context of redemption or reconciliation. Effectively, you’re saying those two things don’t exist anymore. Like there is no coming back from anything, which is kind of terrifying to me when you think about the human condition, if that’s if those are the rules of the game.

Brit Barron: [00:11:13] Totally. You know, what’s hard is we’re seeing a lot of that play out because you’re exactly right. We have some huge social and political issues that are of massive importance that are impacting people’s everyday lives. And I think the question that we need to be asking ourselves is, okay, well, what do we actually want? What are we moving towards? Because if what we want is to say we want to offer a road to liberation and transformation that includes everyone, right? Even people who are on the other side. If we think, okay, this is actually a good way of life, or we think we have found something worthy of sharing, then our response to say and if you don’t understand that, then you’re out. It’s not actually reflective of of that belief, right? If we do believe that, hey, there’s a way forward where every human has dignity and I believe all these things, and that’s why I’m fighting for these things, then it has to include those people, too, or else it’s not true redemption and reconciliation. And I understand that. That’s hard. You know, some days I’m like, uh, it’s easier to sort of sit and say, all right, well, at least me and my group are in. But I think what we’ve done is we’ve made those, those lines so harsh that even in the own groups that we’re a part of and then we ascribe to, we still feel like we’re walking on eggshells. Right? So the belonging, the community, the reconciliation, the redemption, those things all sort of go up on the chopping block when the lines that we draw on the sand are so harsh.

Jonathan Fields: [00:12:40] Yeah. It’s such an important point, right. Because in that last part especially, we may be part of a group or call it a family even, right? Like your immediate family, your extended family, and sort of like everyone takes a hard line on something and you kind of agree with their point of view, but at the same time, it’s not a black and white thing for you and you really want to actually engage. So you can see, like, is there a way for us to bridge a gap or have a conversation hold people to account, but also feel like we can breathe, we can be who we need to be and those immediately around you who you really want to belong to and support are basically saying no. The social pressure on you to actually not voice your own personal desire and willingness to say, no, let’s engage. I mean, it’s got to be stifling. And I would imagine this happens more often than we realize. Yeah.

Brit Barron: [00:13:29] And there’s, you know, a story I talk about in the book, and this was back in 2020. I was having dinner with a group of friends, and one of our friends had mentioned that their grandmother had voted for Trump, and a lot of the friends at the table sort of gasped and when one of our friends said, do you still talk to her? And there was like an air of like a little condescending in that question. And she was like, my nana. Yeah, I still talk to her. And it was this moment where I realized, oh, we don’t even want to let her hold the complexity of everything that her Nana has represented in her life. We want to say, if you have this political division, if your Nana has chosen the opposite side, then she is now on the chopping block. And if you want to stay a part of our group, then you can’t sit in that nuance with her. Right? And that was startling. But I think you’re right. There are a lot of people who belong to families and friends who want to sort of work things out and come to the table, but the social pressure to sort of stay true to whatever way you have aligned yourself with keeps us from engaging in those conversations.

Jonathan Fields: [00:14:40] You know, the way you just described that story. Also, it’s when you have history with people and when this is somebody where they’re either part of your family and you’re supposed to love them, or you genuinely do love them. Like there’s a point of view, a behavior, an opinion that you really don’t agree with. But at the same time, this person is taking care of you. This person has been there for you. This is it’s complicated. I feel like often we tend to conflate behavior with identity and we make the person wrong for existing, not the point of view. I’m curious what your take is on that.

Brit Barron: [00:15:14] Yeah. No, I think that’s exactly right. And part of it, I think, you know, social media has done a lot about our understanding around identity, right. But we sort of exist within the world of our politics in a lot of ways, because that’s what that’s what we see and that’s what people experience us as. And you’re absolutely right. We have conflated some of these ideas with identity. And so in the example of my friend, she has this grandma who made her spaghetti after school and picked her up and went to her dance recital and snuck her cookies when her parents weren’t looking and had all these things. Now this this video that she’s made, is that who she is, right? Or are these some ideas that she’s ascribed to and all these different things? And I think the farther we get down the road of polarization, the more that becomes true. Like, I only need to know one thing about you, and then I’ll know everything about you is sort of how our brain works. And that’s also why cancel culture works on social media. I sell one picture and one lie and one caption, and that’s everything I need to know about who you are. And that’s a dangerous place to be, I think.

Jonathan Fields: [00:16:17] Yeah. We’re really valuing people at these sort of like, you know, like just one trait or one state or one one statement or belief and saying that is the entirety of you. And because of that one thing, I don’t just cancel the belief or the idea, but like you as a human being, aren’t worthy of being in my orbit anymore is dangerous. On the one hand, I understand, especially if there’s current harm being done to you. You know, like, you’ve got to take care of yourself first and foremost. But if you’re resourced to kind of like be in that moment still and then engage and then you feel like you can’t, it just reinforces and deepens the harm and the pain, I would imagine.

Brit Barron: [00:16:55] Yeah. And I’m always an advocate. I tell people, you know, the situation, if this is something that was causing you harm and this is something that is unsafe for you, get out. And I think there are a lot of us who want to be engaging in those ways and feel the social pressure not to. Right. I don’t want to be seen with my super, you know, conservative cousins or I don’t I don’t feel like I’m allowed to have this relationship or hold this nuance or sit in those things. And to that I’m like, that is the exact place you need to be diving in any place that that feels that sort of tension. And you are you are choosing your belonging to sort of this amoeba, you know, this never ending group up here over these relationships with these real people in real life. That is the tension that I think you need to go straight into, because that is where so much of our learning and growth can actually happen.

Jonathan Fields: [00:17:49] That makes sense to me. You write early on, actually in the book, you know, don’t cut these people off, but hold them to account because within if you can do that, if you can engage, that’s where the growth edge is for both of you, actually. Which begs the big question, like how? Like it’s a statement where I’m nodding along. I’m like, well, yeah, that makes sense to me. But the practical realities of that like the how, the strategies, that’s hard.

Brit Barron: [00:18:14] Yeah, it’s super hard. And, you know, something I think about a lot is my own trajectory. Believe it or not, I’m not a person who was born knowing everything I know today. Right. I have had a a huge journey of so many evolving beliefs and ideologies and understanding around the way the world works, and they have been massive. So one person who grew up deeply religious. I grew up very evangelical. I ended up working in the church, and the more I understood more about my own sexuality and my own identity, those things felt conflicting. And so, I mean, I’ve been on such a journey of evolving beliefs, and the temptation for me is to be where I am now. And to say like, this is common sense, you know, and this should be easy, and I should be able to have one conversation with someone and they should see, like the light, you know, or whatever it is that I feel like I’m offering. But the reality is that’s not even how it worked for me. I always joke that when I came out to my parents, I sort of expected something immediately from them. And that same thing took me three years of therapy to find. I thought about the fact that I was gay for three straight years, every single day. And imagine this conversation with my parents. So when I have that conversation with my parents, and I’m expecting in the first five minutes, that same narrative arc. It’s unrealistic. And so when I talk about holding people accountable and saying relationships and nuance and strategy, I think the number one strategy is you have to you have to take into account your own story and take some of the expectation off that you’re going to have, like a magic bullet in one conversation that is going to radically change the trajectory of someone’s life, because that’s probably not what happened for you either.

Jonathan Fields: [00:19:58] I mean, it’s such an interesting point, right? We hold people to a standard of transformation of thought that we don’t hold ourselves to.

Brit Barron: [00:20:09] Yeah, totally. I never read a tweet and then been like, wow, I’m gonna change my entire political ideology. Yeah. That’s it. I’m different.

Jonathan Fields: [00:20:18] Yeah, that’s such an interesting point. And we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. So like reflecting back then on the earlier conversation that you mentioned about your friend sharing, sort of like the story about the grandmother in that moment. Let’s say you’re sitting across from your grandma and you’re and you find out this thing or the grandmother says, like this thing that is just offensive to you or problematic to you, is there sort of like a, like an opening move that that you feel is like fairly good and fairly universal for somebody to, like, respond rather than just recoiling and being shocked, which you’re going to be if you don’t want to disengage and you’re not going to walk away from this relationship. Like what are similarly, the immediate things that you might think about exploring with that person?

Brit Barron: [00:21:08] One of the first things I like to always try to practice myself and recommend is making it personal, right? Because probably the reason that you’re even having the conversation with this person is because there is some sort of personal connection. And so using I statements and acknowledging the experience of, okay, I know that your church may be telling you this, maybe telling you this or you’re experiencing this. However, this makes me feel X. And as someone who loves me, I would like you to know this about me and sort of leverage. Not in a manipulative way, but in an honest way, saying this relationship is important to me and this is how this hurts. I think sometimes, especially politically, we get caught up in like, you know, our parents or grandparents will say something and then be like, did you know that these three legislators got into this? You know what I mean? And then if you want to have an argument, a fact, you absolutely can. But I think a lot of times it’s not going to get you far as sort of exposing some of the truth behind that. I think I’ve had conversations with friends where we finally get to the point where they say, this church may preach things that I don’t agree with, but this is the community that I build a home in. And I’m like, well, now we’re having a different conversation. So we’re not sort of like arguing when the Bible says this about this or this. And I’m saying that’s hurtful to me as a friend because my identity is blank and it feels like you’re preaching me. So I feel like there’s it’s always good to ground and we are two people with feelings, having a conversation about feelings about her, about belonging, and not necessarily two political figures debating.

Jonathan Fields: [00:22:46] Yeah, take it back down to just two people. And you brought up something really interesting also just now, which is the notion of belonging. You know, we are driven so much by affiliation and status and the need to belong. You know, and when we find that, I think it’s also it’s harder to find these days for a lot of people. You know, a lot of places, a lot of people looked for it now, aren’t really providing that anymore. So when we find it, we’re like, we just lock onto it or like, this feels good. I want to stay in this feeling. And then when the group to which you find that sense of belonging and affiliation has a set of beliefs, and if you don’t kind of toe the line of those beliefs, you fear no longer being cast out. Stout. Basically, even if you kind of don’t really believe it, you’ll tell yourself that you do because that need to belong is so strong. I wonder what your sense is in how much that plays into these dynamics too.

Brit Barron: [00:23:44] Oh, I think it’s huge. I think it’s everywhere. There’s another story I talk about in the book of watching a documentary about flat earthers. You know, some folks who believe the earth is flat, and this man is doing interviews with people who are at this conference, and he sits down with this one man and is, you know, the interviewer is sort of saying, what about all this data and these nuances of the earth being round? And, and the man sort of stopped him and said, listen, honestly, it’s really hard to make friends and being a part of this group, I go to two conferences a year. We’re on a Facebook group. These are the people who feed my cats when I go into town, and there was no arguing with that, I don’t know. This man really doesn’t care what shape the earth is. He’s like, who’s gonna feed my cats when I go out of town? And I think we severely underestimate our human need to belong, and the ways in which rearrange the theological and ideological furniture in our brain as much as we need to, to stay in that belonging. And so I think in some ways, we have experienced that in helpful ways when we physically gather, I think when we understand ourselves as trying to belong to a virtual community or a a political ideology, then we find ourselves drawing harder lines of, okay, well, I can’t be seen talking to you, or I can’t seem like I’m unsure about that, or I have to repost this, or everyone in my group is saying this. I have to say it because I need to belong to something. I don’t want to be on the outside of this group, and I think that drives far more of our behavior than any of us I think want to acknowledge.

Jonathan Fields: [00:25:21] Yeah, I so agree with that. Which makes me wonder if you’re going to have a conversation with this other person. I wonder if part of that is like you asking yourself a question, which is something along the lines of what am I asking them to say no to in the name of saying yes to me? And like trying to wrap your head around that, because we probably don’t ever really go deep into that.

Brit Barron: [00:25:43] Yes. And I think that is I think that’s a great question to ask. And I think that’s a hard question to ask. And I think that would create a lot of empathy as we move into some of these difficult conversations. Just being the person that I am, I’m in my experiences in life and coming out and getting married to a woman and all these things. I’ve had incredibly supportive parents who have been on this journey of evolution and arrived at this very, very supportive area. But as it has definitely cost them belonging in communities that they were a part of, and that was really hard for me to sort of navigate. And so I think sometimes when we are quick to say, hey, drop everything, change everything. Yeah, I think it’s, it’s it would be really empathetic and compassionate to ask that question. What will coming on this journey with me require of you? And that is that’s a beautiful question.

Jonathan Fields: [00:26:39] What am I asking you to leave behind? Also that you value it is. And it brings up the topic of empathy also, which you speak about and you write about. And it’s such an interesting topic in this conversation too, because I’ve had a conversation with folks saying, in a dynamic like this, they don’t actually deserve my empathy. Like, they don’t deserve compassion for me, especially if they’re causing harm to me. Like current harm to me. Like, why is it my job to try and empathize with them? Why is it my job to do the emotional labor of finding a place of compassion for them when they’re causing me harm? Talk to me about this dynamic because I think it comes up more than we probably voice.

Brit Barron: [00:27:21] Yeah. Well, I think being able to find compassion and empathy for people who are on the other side of whatever line that we’ve drawn isn’t only something that we do in service to them, it’s something that we do in service to ourselves as well. And I think we’re not always the ones. Right, because I have found that compassion, and maybe that empathy doesn’t mean that I need to necessarily be the one in the conversation with you. There’s a certain amount of harm being done, and my ability to still empathize is going to serve me in my journey towards liberation and freedom and wholeness. I think the number one thing that has been able to help me in my journey of finding empathy for folks who disagree, who believe things that I feel to be deeply problematic and and troublesome and hurtful to the world, is my ability to have empathy for the version of myself that believed those things, the versions of myself that existed before this one, the version of me that was very comfortable sitting in seats where people sit now, and that’s the work that I do, is to try to get them out of those seats. Right. And so I think there’s a an author and I can’t remember their name right now, but they talk about the reality that people who have been liberated from something do have more responsibility when it comes to the act of liberating those who are still under that oppressive structure. Is it fair? Absolutely not. But is it true that if what you want is liberation and freedom and wholeness, then you are probably experiencing something that those people that you are still in contact with, our community who have hurt you or whatever the situation is you have experienced in something that they haven’t experienced.

Brit Barron: [00:29:08] And so the responsibility falls unfairly on the person who has experienced freedom and liberation. I go back and forth, right? I’m saying all these things as like, this is the ideal, but I’m also a real person. And some people I’m like, sure, I’m a believer, and maybe tomorrow. But when I can find that empathy for those burdens on myself, it’s easier for me to find for someone else and to know why is the responsibility on me? Because I’m the one who has found liberation and who is seeking transformation and freedom, and I want other people to have that experience. Most of the time I think what I see a lot on the internet, when I go into comment sections, they may be saying different things about different topics, but what I hear is I feel shame and I want you to feel it too, right? So I’m hurt and I want you to hurt too. When the reality is, what I hope we might say is I have found liberation. And I want that for you too. I have experienced freedom, and I want that for you, too. And I think that would change the trajectory of the work. Again, it doesn’t change the work at hand, but it would change our approach to the work if we sort of fundamentally wanted that for a broader humanity.

Jonathan Fields: [00:30:15] No, that makes a lot of sense to me. I mean, you mentioned one of the things that you would sometimes do is sort of look and say, well, that was me. Not too long ago. So, like, how did I feel like. Can I sit in that seat? Like, back then when I was that person with those beliefs, in that sense of identity and try and understand empathetically from that point. I think it’s helpful when you were that person, but oftentimes you weren’t. You’ve never actually had that experience to draw from, to try and find empathy. I understand your beliefs. I’m just I’m really curious. Like, not in a judgmental way, but like, where did they come from? Like what? Tell me where? Like what’s underneath these for you? Which, again, is sort of like a, you know, like a stab at empathy. But I also feel like if we can understand what’s underneath those, oftentimes we can find more commonality than we realize exists. I’m curious what your take is on that.

Brit Barron: [00:31:08] Yeah, I think so. My you know, my dad used to always say the three strongest words in the English language are help me understand. So starting off a conversation with. Yeah, help me understand. Not in a judgmental way, but truly help me understand how this became the framework through which you understand. Help me understand this. You know, I have people in my own life through which I don’t speak to anymore that were a harmful relationships, that I felt as though a boundary was needed. And I can totally look the more context I have in their life and understand, oh my gosh, that is how you got that framework and that is why you’re doing it. And then does it mean that there again is no accountability, that there are no consequences for people’s actions, but our ability to relate on a human level of understanding with how people have arrived at certain frameworks and certain behaviors, again, is going to do us a great service as we move forward in whatever work we’re trying to do. And so I think help me understand context is everything. We always say you can’t understand content without context. And so yeah, who is this person talking to me? And where did these beliefs come from, and how might that impact how I understand the way you are moving in the world.

Jonathan Fields: [00:32:27] I love those three words. Yeah, it’s so powerful, right? Because I think sometimes we have the impulse to want to understand. Maybe not, but sometimes we do. And but it doesn’t come out as help me understand and sort of like a kind way. It’s sort of like, tell me why this is true, or prove to me that, like your point of view, it’s like it feels like an attack rather than a genuine inquiry. And I wonder whether that’s because sometimes we forget that there is actually a human being with like, a heart and a soul and a mind and all the things beneath the point of view that is tender, just like we are. And nobody likes to be attacked. But people really love to be understood.

Brit Barron: [00:33:08] Yeah. I mean, I think we all want to be understood, right? I think sometimes I can look at certain people who exist in the world in different way than I do and experience it in a different way, and it would be a lot easier. Instead of help me understand, it’d be a lot easier to be like, why are you like that? Right? Why do you just stop? You know, I think.

Jonathan Fields: [00:33:28] I probably uttered those words myself.

Brit Barron: [00:33:30] So yes, literally. But there’s so much beauty in. And again, this is all assuming that there’s a context in which there is enough safety to sit down and engage in this. And when that exists and when you can, I think there’s no more beautiful experience than understanding and getting more context for why a person feels the way they do, even if you don’t agree. I remember sitting with, um, someone who was a friend of a friend, and we sort of had this little interaction at a dinner party that didn’t go super well. Uh, it was a political conversation came up. And, you know, I circled back and was like, I would love to to circle back to this conversation. And so we ended up grabbing coffee and I listened. And he different social identity than me. He was a straight white man, and he was telling me how it felt to be him. And I struggled to at first understand what that was, and I had to remind myself, I just asked him to tell me this. Listening to him and empathizing it, and realizing that this is real for him doesn’t mean that I also think it has to be true in what’s happening in the world. But I can acknowledge that this is his real experience, and if I can do that, then we can actually continue and have this conversation. And I think sometimes our fear is that if I understand someone, then I agree with them. Um, when I’m happy to just say, oh, I understand that that’s real for you, and that’s not my understanding of the world. And those two completely opposite things can both be true. Yeah.

Jonathan Fields: [00:35:11] This is an important fear I think you’ve identified. Like if if I understand them, then I agree with them. And that’s not true. But sometimes we do conflate those, right? We’re kind of like, I can’t go all the way and understanding because then that means I accept, I agree, and it becomes a barrier and we’ll be right back after a word from our sponsors. You also brought up the notion of boundaries just before, which I think is something that everybody struggles with in all different contexts in life, but especially in these contexts and especially in the context of somebody you want to keep in your life. Like that grandma example we started out with. Right. But you also need to feel okay. You need to feel safe. Talk to me first. When you use the word boundaries, because I think that’s one of those sort of like nebulous words that people kind of mean different things when they talk about it sometimes. What are we actually talking about? Like when you talk about boundaries, what are you talking about?

Brit Barron: [00:36:04] Yeah. So I think boundaries are the ways in the, the rules in which you have set for yourself and the way you will engage with certain relationships. I always say, because a man’s people say they broke my boundary or they didn’t respect my boundary. And I think on some level, obviously that’s possible. But more often than not, the boundary is something that we are responsible for. So we have created and we uphold and we stand to. So a boundary and this isn’t relational right. But this is an example during this election cycle because I don’t want to be overwhelmed. I have a boundary that I have set that I will engage with the news. One time a day I will read only no video, and then I will wait until the next day and the next news cycle. And I will not get sort of like sucked in. So that’s just that’s a boundary that I have that has a time line on it. This is for election season, how I will engage with the news. And so it’s just parameters that we create around relationships or behavior.

Jonathan Fields: [00:37:09] I mean that’s interesting, right? Because the one with the news, I think a lot of people think about boundaries as this is a boundary and it’s got to be in relation to other people. But your example is interesting, right? Because it’s like, no, actually they’re probably all sorts of different domains in our lives where boundaries would really be helpful and they don’t always have to be in relation to specific other people or conversations or relationships, like with news, having apps on your phone like social media, those are really interesting. What’s not present in those though, is okay, so that’s a boundary that you set for yourself. And what’s not on the table with that is communicating them and interacting with somebody else around them. So when we actually are talking about other people, take me into how that changes things.

Brit Barron: [00:37:56] Well, that’s a very layered dynamic, right? The news isn’t going to text me and say, why aren’t you watching me? And you used to watch me all the time. And so I think communication around boundaries is incredibly important. And I think this comes back to sometimes we have this idea It comes from societally. It’s reinforced a lot that if something is like difficult or uncomfortable, it equals bad. And I think our rejection of that idea is going to be incredibly helpful in how we navigate boundaries. Right? Because there’s a lot of uncomfortable conversations and situations where you say, hey, for where I am right now, this isn’t a healthy pattern of relationship for me to be in. And I’ve had those uncomfortable conversations with friends, with family members where I’ve said, hey, and I’m 100% take the onus. I am choosing this boundary because I think it’s what I need right now. I think it’s always helpful to to understand that responsibility. It gets a little tricky when we put it out, like, because you’re like this, I’m doing this. And so when we simply say, this is what I’m choosing because it’s best for me, and then we have to hold to our boundaries and which can also be difficult. And the last thing about boundaries that I feel like sometimes we miss, that I think is incredibly important, is we make boundaries. We act on them, and then we should be in the in the business of regularly reassessing our boundaries. Is this still something that is good for me? Or. I actually thought I wanted to come to the table and navigate and sit in this new to this person. It’s actually turned out to be incredibly harmful. I need a stronger boundary or okay, I set that really strict boundary, but I’m missing this person. I feel like I have what it takes to sort of be at the table and say the nuance. I’m going to loosen the reins a little. Every time we get new information we feel like we are experiencing. I think boundaries are something that we should always be reassessing to say, does this still feel right to me?

Jonathan Fields: [00:39:47] I wonder if sometimes we don’t do that because we want to be perceived as being consistent people, you know, like, rather than, oh, you’re so flaky. Like yesterday you said this wasn’t okay, and today you’re saying it is now or like what’s right. Like, who are you? Or are you just shape shifting to meet the moment? And we like to be perceived as sort of like being a person who has certain boundaries, certain lines in the sand and like that were reinforcing them. And also, I wonder if part of it also is we feel like if we loosen up a boundary or something that we’re, quote, caving in, that we’re not we’re not strong enough to support this thing, even though we still believe in it and we still need it. So we just kind of hold rigidly to it. I feel like so much of this is, you know, it’s about other people’s perception. We get so wrapped up in that.

Brit Barron: [00:40:36] Yeah. And I think it goes back to the conversation we were having earlier. Right. Is I’m sure we want to be perceived in that way and maybe even perceived in that way from ourselves as well. And sure, maybe if every single day a boundary is different, then okay, maybe stop reassessing for a minute and have a have a season. But at the same time, I think there is something beautiful in being able to acknowledge and appreciate that something about you has changed, and therefore the framework through which you see the world has changed and the way you experience things has changed, and the way you can show up in relationships has changed. And I think sometimes we say, oh, well, I drew a line in the sand, so now I just have to stick it out on this decision when, you know, I’m one of those people that was like, if the election goes a certain way, I’m leaving the country and like, I did it and literally still here and, you know, we just we sometimes we make these statements. And if we get into the, the pride center of our brain that says, well, I already dug my heels in the sand and I don’t want to let them go, so I’m just going to dig them deeper. Then what even example are we setting of what we believe about the ability to change minds and to transform and to believe something, and then to change our mind is part of what it means to be human. And that’s the work that I want to invite people in my life to. So I have to be true to that as well.

Jonathan Fields: [00:41:55] Yeah, it seems like it would be a good idea to regularly, when you think about your boundaries, ask, is it still serving me? And if it’s not, then revisit it. You know, I could imagine a scenario also where you set a really strong boundary because you just maybe you just You’re going through something, you’re really not well resourced and you have you’re depleted because you’re burned out, you’re overwhelmed. Or maybe just there’s a lot happening, or maybe you’re struggling with mental health and you’re like, I need to put up boundaries. Like there’s a conversation about a topic I care about, but I actually am not in a place where I can actually be okay in that conversation right now. So I need to put up this boundary. And then maybe six months later, you know, like you’re you’re in a different place. You’ve been working with a therapist, you’re easing your way back out of mental health. And actually, you really now you really actually want to engage around this. You feel like you’re resourced, you’re well prepared for it, and it matters to you. And you’re like, oh, I don’t need this boundary anymore. Like it’s no longer serving me. Now I actually want to step into the conversation. Does that make sense to you?

Brit Barron: [00:42:54] Yeah, 100%. I mean, again, to use the example of the news, right. It’ll change in a less heightened climate. But to say, right now, I’m so already overwhelmed with information that I need to have some kind of information boundary or I mean, a perfect example of this is parents, I mean you. Everything has to shift. When you have a newborn. Everything changes. Every single part of your schedule, the conversations you have, the conversations you even have the capacity for. You’re like, I’m on three hours of sleep. My friends with newborns, they’re like, respectfully, don’t call me about your problems. You’re either dropping off dinner or I don’t want to hear it and not make sense to me, because that is sort of where they are. And so if we are able to then say, yeah, where am I? And does this boundary still make sense for me? I think it would be a great thing to practice.

Jonathan Fields: [00:43:43] Yeah, that makes sense. One of the things that was just coming up, as you’re describing that, um, I wonder sometimes we do you think that there are moments where we use boundaries as justification for just not wanting to be uncomfortable in a conversation that actually would probably be important to have?

Brit Barron: [00:44:06] Yeah. And also I have definitely done that. You know, I think I’ve been I had done that before and I think a lot of us have. I think we’re in a funny era of time where we have the most information around mental and emotional health than we’ve ever had relational health. Like, there are so many experts so readily available. I think there are a lot of ways to, in a sense, bypass some things that might be actually for our health and our benefit, but that we don’t like. And I think boundaries is one of those things where we can say, hey, this is a boundary for me. You’re not respecting it. And that may be our way of avoiding a conversation that we really should have. Totally. I get asked a lot of questions about like, okay, just lay it out for me. When is this? When is the boundary? When do I reassess? When is it right? When is it harm? When is it too much harm? And the unfortunate reality is that we don’t live in an algebra book, right? Where I can say, oh, okay, let me just put it into my algorithm. So your grandma was this nice, but then she said something this offensive looks like you can still go to holidays with her. You know, there is no sort of A plus B equals C. And so you really have to get comfortable with trusting and understanding your own intuition, with having wise people in your life or loving people in your community who you believe in and who you feel like you can trust to sort of navigate each situation as it comes up.

Jonathan Fields: [00:45:34] Yeah, that makes sense to me. As much as we all want the universal formula that’s just like this applies to everybody the same way, right? No matter how different we are, no matter how different the circumstance is, we just we want this system, the formula that just makes it all okay. I’m curious also, I mean, you kindly shared your experience coming out with your folks who came from like this deeply religious evangelical background, but eventually came around. And can you share a little bit more about the evolution, like how that unfolded. Because I’m curious. You know, that’s sort of like a macro lens of of what we’re talking about here. And was it through a series of conversations? Was it just slowly over time? Was it their own sort of like inquiry and contemplation or some blend of all of that?

Brit Barron: [00:46:20] Yeah, it was definitely a blend. You know, it started as conversations between me and them, and I think those were helpful but also limited and just we have such a specific parent child dynamic, right. Because they are my parents, I am their child. And something that really moved the needle for them was they actually found a couple people. It was actually some coworkers of my dad’s who were also very religious, whose children had also came out, and they said, hey, we actually meet with a group of parents who are working through this. Then they did that. They read books, we continued conversations, and they’re so loving and they always love me. And and they’ve always had such a kindness and a love towards me. But the ideology of it did take sort of this arc to go from, okay, we love you right all the way until like, oh my gosh, we fully like, support and stand by and are happy for you. And Sammy’s my wife and you know the life that you’re building together. I think there were a few times where I could say, I could have said like, okay, this is your chance. Be fully on board or get, you know what I mean, or get out. And I think I want to acknowledge that there was effort also being made that I could see. But yeah, it was totally a journey. That was me. That was other people, their friends, this little group, they became a part of books. They read, things they experienced, conversations they had, and they had people in their lives who were pushing back on the other end saying, what about this? You know, and they sat in the middle of that and work through that tension. So it was definitely a long arc of change.

Jonathan Fields: [00:48:03] Yeah, but I mean, it sounds like there’s that. There was always that underlying fabric of love that was motivation to try and to stay in the conversation. Right. I wonder also, circling back to the earlier part of our conversation, whether them finding this other small group of parents who had similar beliefs and yet were grappling with the same question, it almost like maybe gave them a new place to find, like a new microcosm of belonging, of folks who shared that fundamental belief, but also were in this same question where they could have affiliation and belonging with them instead of solely relying on the community at large, which wasn’t in that same place. And whether that really helped them sort of like solve for that part of the human experience while they were grappling with this.

Brit Barron: [00:48:52] Yeah, I think so. And I think that and I’m hearing you say that, I’m like, I’m sure that was actually a maybe a bigger game changer for them than I thought. Right? Because what was at stake for them in accepting and and becoming affirming and supportive of us was their community. And I recognize how hard that is and was and has been.

Jonathan Fields: [00:49:12] Yeah. I want to come full circle. Earlier to our conversation, we were talking about this notion. We started talking about a lot around cancel culture and also redemption and reconciliation. And I feel like underneath so much heat that’s being generated in conversation now, especially in conversation around tech communities and families where we don’t want to opt out of those, but we don’t see an easy path to reconciliation or a path to redemption when you’re in that circumstance. Like, is there anything, any are there any practices or questions or explorations or conversations that you feel have been super helpful in maybe just starting to open the door to that?

Brit Barron: [00:49:55] Yeah, I think how we frame is, is everything right? I mean, we talked so much already about people wanting to be understood, about wanting to belong. And I think even opening the door to some of these conversations can look just like saying, hey, something has been on my mind. I would love to share with you all, and maybe you don’t have to phone right now. It doesn’t have to be a whole thing. I’m not trying to startle whatever. This is just something that I’ve been thinking about that’s been heavy on my mind or heavy on my heart. I think it’s a reminder that I know so many things feel very urgent, but change almost never is. Change never bends itself to our timeline. And so in starting these conversations and engaging them with our family, I think it’s good to first put down expectations of, okay, I’m going to bring this up at Sunday dinner. And so that Monday morning we can all be on the same page. I think it’s just so good to remember that you’re doing just that. You’re just starting the conversation that may just go in and out for years. And I think, you know, I’ve had this conversation with a lot of friends where we’re like, it’s okay to hang out with your family and just keep it to the topics that everyone agrees on sometimes, like I think it’s bring these things up, stay true to what you believe, start those conversations. And it doesn’t have to be every single time you see your mom. And I think there are times where you can just say, hey, for this dinner, for this holiday or this Thanksgiving, we’re going to keep it to the things we agree with. Because again, I belong to this and I’m in it for the long haul. And so that doesn’t mean that every single time I need to be like drilling this conversation down, it can be a slow burn. And I think that’s also very okay.

Jonathan Fields: [00:51:43] Yeah, I love that sort of, you know, like there’s grace in creating some space, right? And giving some, some time to let things unfold without walking away. But just like extending the window of time that you’re sort of like in this feels like a good place for us to come full circle as well. So in this container of Good Life Project., if I offer up the phrase to live a good life, what comes up?

Brit Barron: [00:52:05] Wow. I think the first thing that came to mind was to live a good life is to be fully present.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:10] Mm. Thank you.

Brit Barron: [00:52:12] Yeah. Thank you.

Jonathan Fields: [00:52:15] Hey, before you leave, if you loved this episode, safe bet. You’ll also love the conversation that we had with Prentice Hemphill about finding wholeness in your relationships and the world around you. You’ll find a link to Prentice’s episode in the show notes. This episode of Good Life Project was produced by executive producers Lindsey Fox and me, Jonathan Fields. Editing help by Alejandro Ramirez. Kristoffer Carter crafted our theme music and special thanks to Shelley Adelle for her research on this episode. And of course, if you haven’t already done so, please go ahead and follow Good Life Project. in your favorite listening app. And if you found this conversation interesting or inspiring or valuable, and chances are you did, since you’re still listening here, would you do me a personal favor? A seven-second favor and share it? Maybe on social or by text or by email? Even just with one person? Just copy the link from the app you’re using and tell those you know, those you love, those you want to help navigate this thing called life a little better so we can all do it better together with more ease and more joy. Tell them to listen, then even invite them to talk about what you’ve both discovered. Because when podcasts become conversations and conversations become action, that’s how we all come alive together. Until next time, I’m Jonathan Fields, signing off for Good Life Project.